capecitabine

154361-50-9

- R-340, Ro-09-1978, Xeloda

pentyl [1-(3,4-dihydroxy-5-methyltetrahydrofuran-2-yl)-5-fluoro-2-oxo-1H-pyrimidin-4-yl]carbamate

MONDAY Sept. 16, 2013 — The first generic version of the oral chemotherapy drug Xeloda (capecitabine) has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat cancers of the colon/rectum or breast, the agency said Monday in a news release.

This year, an estimated 142,820 people will be diagnosed with cancer of the colon/rectum, and 50,830 are predicted to die from the disease, the FDA said, citing the U.S. National Cancer Institute. An estimated 232,340 women will be diagnosed with cancer of the breast this year, and some 39,620 will die from it.

The most common side effects of the drug are diarrhea, vomiting; pain, redness, swelling or sores in the mouth; fever and infection, the FDA said.

The agency stressed that approved generics have the same high quality and strength as their brand-name counterparts.

License to produce the generic drug was given to Israel-based Teva Pharmaceuticals. The brand name drug is produced by the Swiss pharma firm Roche.

Capecitabine (INN) /keɪpˈsaɪtəbiːn/ (Xeloda, Roche) is an orally-administeredchemotherapeutic agent used in the treatment of metastatic breast andcolorectal cancers. Capecitabine is a prodrug, that is enzymatically converted to 5-fluorouracil in the tumor, where it inhibits DNA synthesis and slows growth of tumor tissue. The activation of capecitabine follows a pathway with three enzymatic steps and two intermediary metabolites, 5′-deoxy-5-fluorocytidine (5′-DFCR) and 5′-deoxy-5-fluorouridine (5′-DFUR), to form 5-fluorouracil

Indications

Capecitabine is FDA-approved for:

- Adjuvant in colorectal cancer Stage III Dukes’ C – used as first-line monotherapy.

- Metastatic colorectal cancer – used as first-line monotherapy, if appropriate.

- Metastatic breast cancer – used in combination with docetaxel, after failure of anthracycline-based treatment. Also as monotherapy, if the patient has failed paclitaxel-based treatment, and if anthracycline-based treatment has either failed or cannot be continued for other reasons (i.e., the patient has already received the maximum lifetime dose of an anthracycline).

In the UK, capecitabine is approved by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) for colon and colorectal cancer, and locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer.[1] On March 29, 2007, the European Commission approved Capecitabine, in combination with platinum-based therapy (with or without epirubicin), for the first-line treatment of advanced stomach cancer.

Capecitabine is a cancer chemotherapeutic agent that interferes with the growth of cancer cells and slows their distribution in the body. Capecitabine is used to treat breast cancer and colon or rectum cancer that has spread to other parts of the body.

Formulation

Capecitabine (as brand-name Xeloda) is available in light peach 150 mg tablets and peach 500 mg tablets.

WO2009066892A1

Capecitabine is an orally-administered anticancer agent widely used in the treatment of metastatic breast and colorectal cancers. Capecitabine is a ribofuranose-based nucleoside, and has the sterochemical structure of a ribofuranose having an β-oriented 5-fluorocytosine moiety at C-I position.

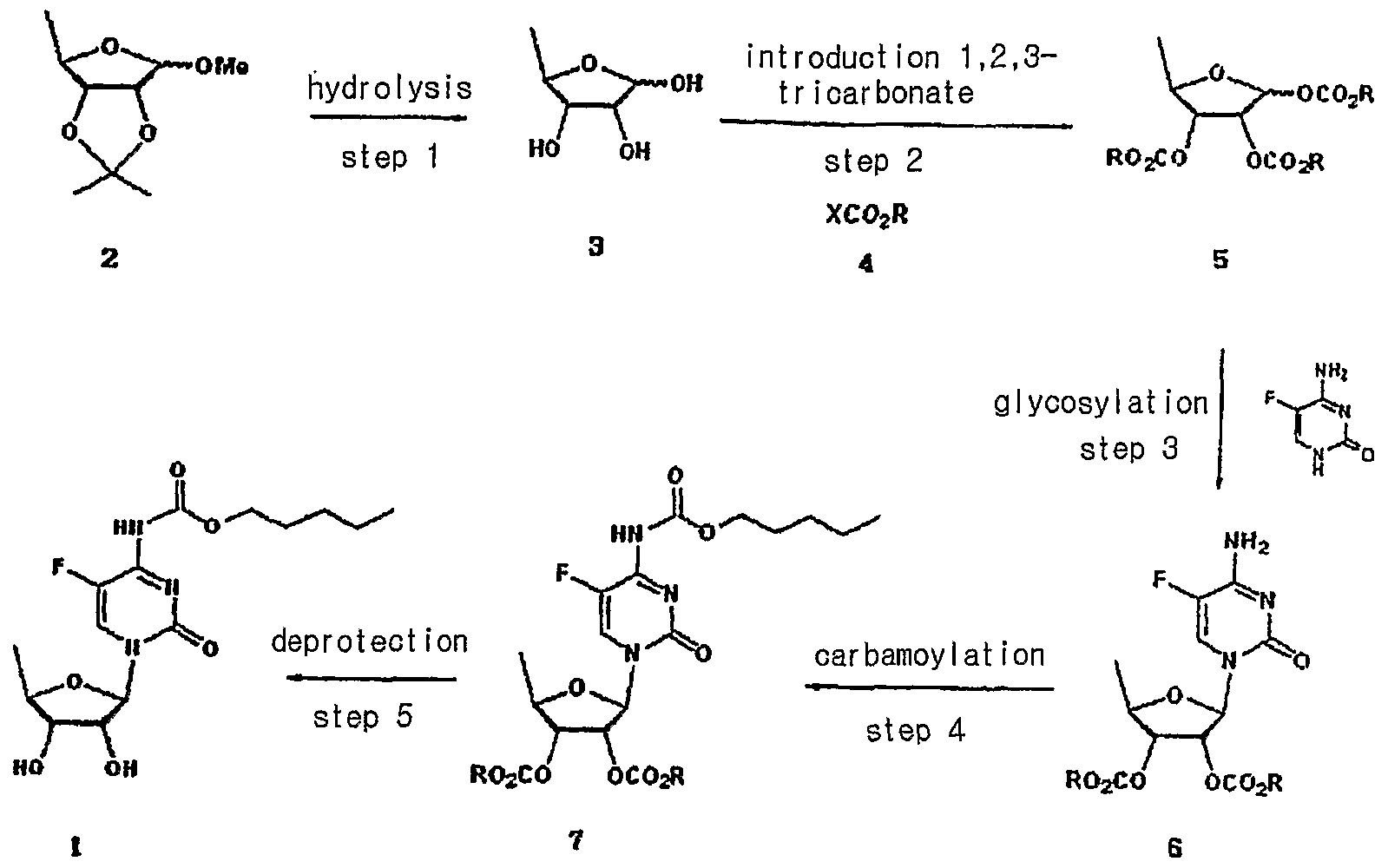

US Patent Nos. 5,472,949 and 5,453,497 disclose a method for preparing capecitabine by glycosylating tri-O-acetyl-5-deoxy-β-D-ribofuranose of formula I using 5-fluorocytosine to obtain cytidine of formula II; and carbamoylating and hydrolyzing the resulting compound, as shown in Reaction Scheme 1 :

Reaction Scheme 1

1

The compound of formula I employed as an intermediate in Reaction

Scheme 1 is the isomer having a β-oriented acetyl group at the 1 -position, for the reason that 5-fluorocytosine is more reactive toward the β-isomer than the α-isomer in the glycosylation reaction due to the occurrence of a significant neighboring group participation effect which takes place when the protecting group of the 2-hydroxy group is acyl.

Accordingly, β-oriented tri-O-acetyl-5-deoxy-β-D-ribofuranose (formula

I) has been regarded in the conventional art to the essential intermediate for the preparation of capecitabine. However, such a reaction gives a mixture of β- and α-isomers from which cytidine (formula II) must be isolated by an uneconomical step.

Meanwhile, US Patent No. 4,340,729 teaches a method for obtaining capecitabine by the procedure shown in Reaction Scheme 2, which comprises hydrolyzing 1-methyl-acetonide of formula III to obtain a triol of formula IV; acetylating the compound of formula IV using anhydrous acetic anhydride in pyridine to obtain a β-/α-anomeric mixture of tri-O-acetyl-5-deoxy-D-ribofuranose of formula V; conducting vacuum distillation to purify the β-/α-anomeric mixture; and isolating the β-anomer of formula I therefrom:

Reaction Scheme 2

III IV

However, the above method is also hampered by the requirement to perform an uneconomical and complicated recrystallization steps for isolating the β-anomer from the mixture of β-/α-anomers of formula V, which leads to a low yield of only about 35% to 40% (Guangyi Wang et al., J. Med. Chem., 2000, vol. 43, 2566-2574; Pothukuchi Sairam et al., Carbohydrate Research, 2003, vol. 338, 303-306; Xiangshu Fei et al., Nuclear Medicine and Biology, 2004, vol. 31, 1033-1041; and Henry M. Kissman et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1957, vol. 79, 5534-5540).

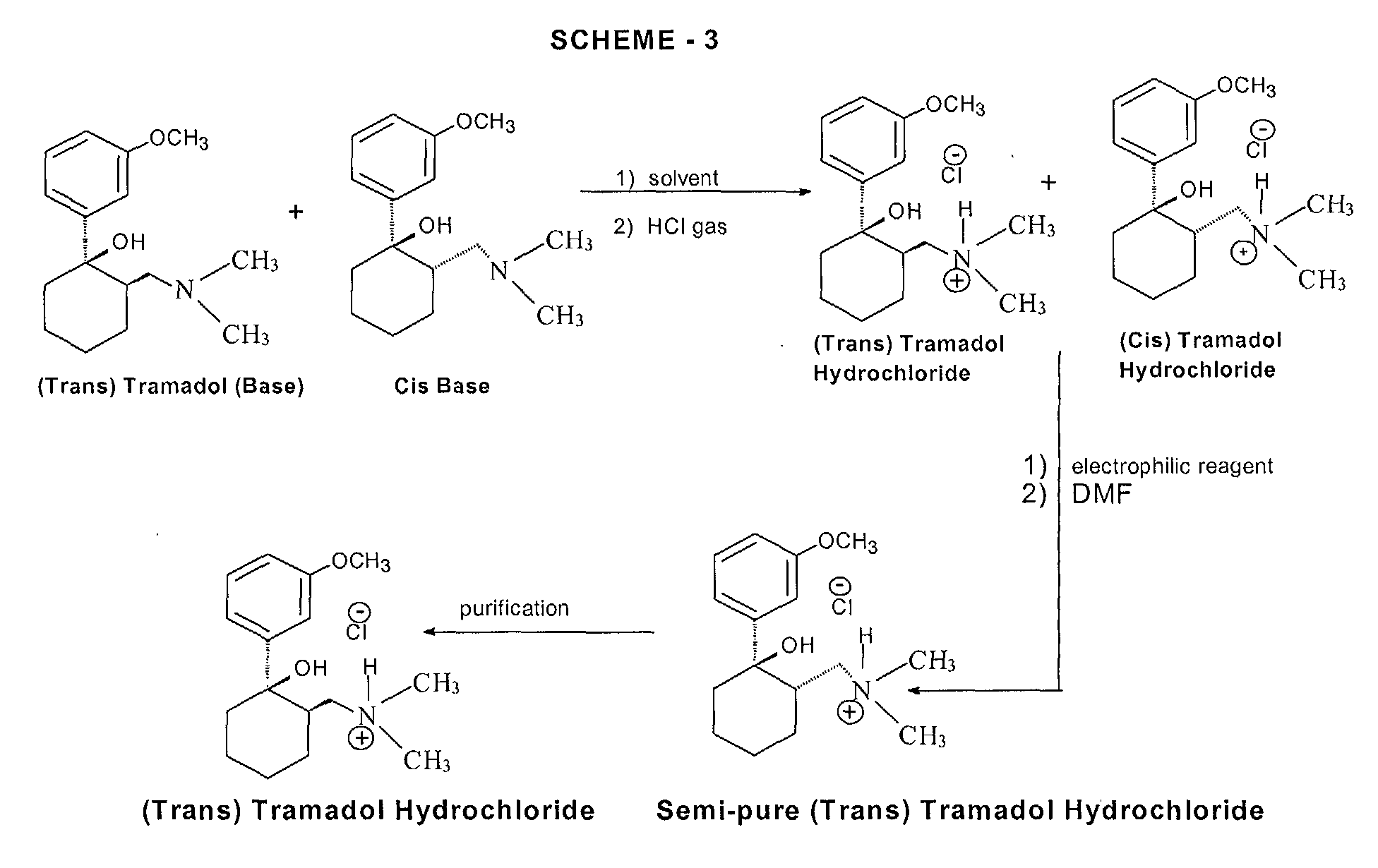

Further, US Patent No. 5,476,932 discloses a method for preparing capecitabine by subjecting 5′-deoxy-5-fluorocytidine of formula VI to a reaction with pentylchloroformate to obtain the compound of formula VII having the amino group and the 2-,3-hydroxy groups protected with C5Hi1CO2 groups; and removing the hydroxy-protecting groups from the resulting compound, as shown in Reaction Scheme 3 :

Reaction Scheme 3

Vl VII 1

However, this method suffers from a high manufacturing cost and also requires several complicated steps for preparing the 5′-deoxy-5-fluorocytidine of formula VI: protecting the 2-,3-hydroxy groups; conducting a reaction thereof with 5-fluorocytosine; and deprotecting the 2-,3-hydroxy groups.

Accordingly, the present inventors have endeavored to develop an efficient method for preparing capecitabine, and have unexpectedly found an efficient, novel method for preparing highly pure capecitabine using a trialkyl carbonate intermediate, which does not require the uneconomical β-anomer isolation steps.

synthesis

WO2010065586A2

more info and description

Aspects of the present invention relate to capecitabine and processes for the preparation thereof.

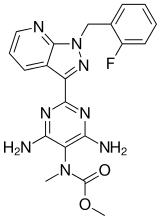

The drug compound having the adopted name “capecitabine” has a chemical name 5′-deoxy-5-fluoro-N-[(pentyloxy) carbonyl] cytidine and has structural formula I.

H

OH OH I

This compound is a fluoropyrimidine carbamate with antineoplastic activity. The commercial product XELODA™ tablets from Roche Pharmaceuticals contains either 150 or 500 mg of capecitabine as the active ingredient.

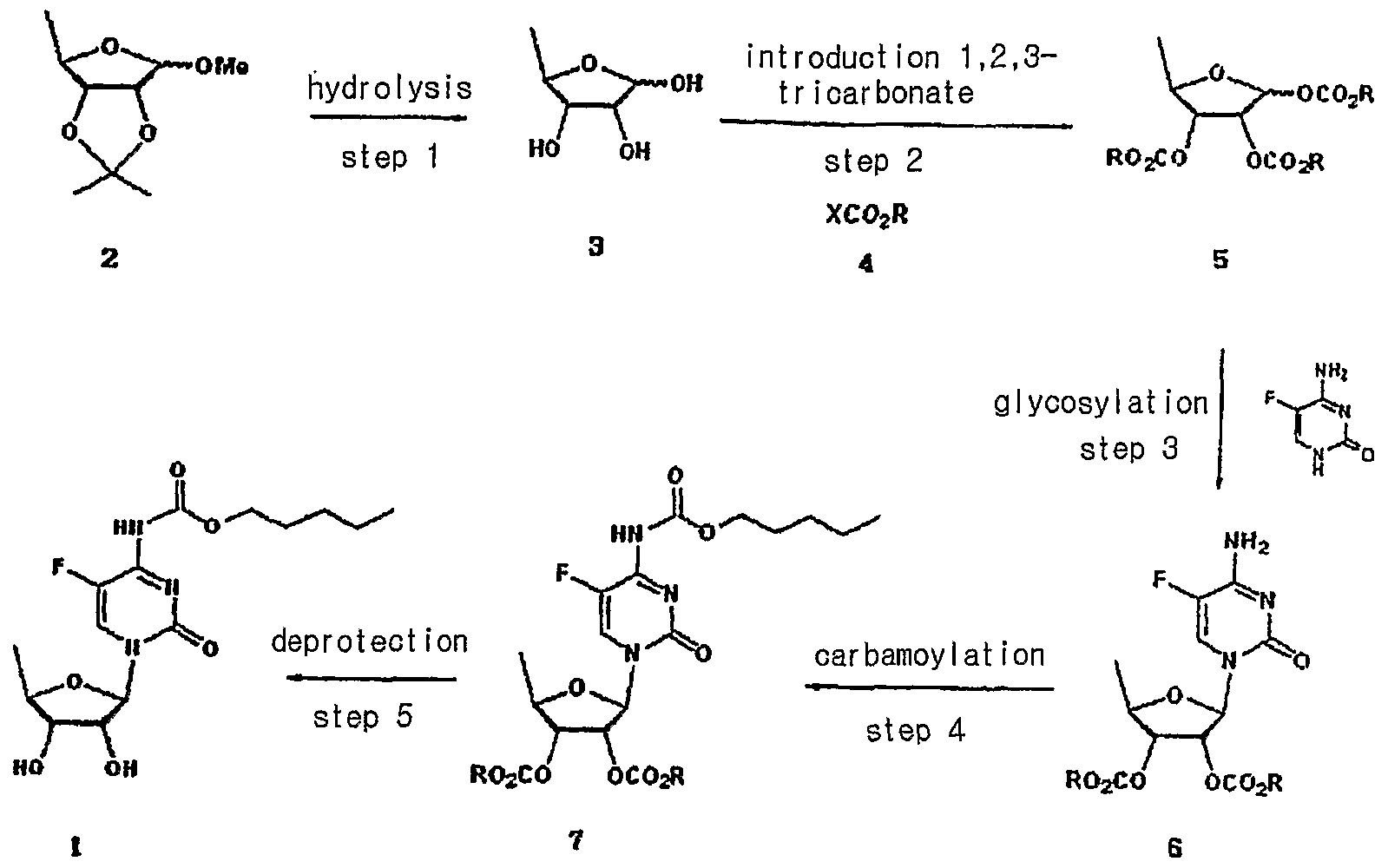

U.S. Patent No. 4,966,891 describes capecitabine generically and a process for the preparation thereof. It also describes pharmaceutical compositions, and methods of treating of sarcoma and fibrosarcoma. This patent also discloses the use of ethyl acetate for recrystallization of capecitabine. The overall process is summarized in Scheme I.

Scheme I

U.S. Patent No. 5,453,497 discloses a process for producing capecitabine that comprises: coupling of th-O-acetyl-5-deoxy-β-D-hbofuranose with 5- fluorocytosine to obtain 2′,3′-di-O-acetyl-5′-deoxy-5-fluorocytidine; acylating a 2′, 3′- di-O-acetyl-5′-deoxy-5-fluorocytidine with n-pentyl chloroformate to form 5′-deoxy- 2′,3′-di-O-alkylcarbonyl-5-fluoro-N-alkyloxycarbonyl cytidine, and deacylating the 2′ and 3′ positions of the carbohydrate moiety to form capecitabine. The overall process is summarized in Scheme II.

Capecitabine

Scheme Il

The preparation of capecitabine is also disclosed by N. Shimma et al., “The Design and Synthesis of a New Tumor-Selective Fluoropyrimidine Carbamate, Capecitabine,” Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry, Vol. 8, pp. 1697-1706 (2000). U.S. Patent No. 7,365,188 discloses a process for the production of capecitabine, comprising reacting 5-fluorocytosine with a first silylating agent in the presence of an acid catalyst under conditions sufficient to produce a first silylated compound; reacting the first silylated compound with 2,3-diprotected-5- deoxy-furanoside to produce a coupled product; reacting the coupled product with a second silylating agent to produce a second silylated product; acylating the second silylated product to produce an acylated product; and selectively removing the silyl moiety and hydroxyl protecting groups to produce capecitabine. The overall process is summarized in Scheme III. te

R: hydrocarbyl

Scheme III

Further, this patent discloses crystallization of capecitabine, using a solvent mixture of ethyl acetate and n-heptane. International Application Publication No. WO 2005/080351 A1 describes a process for the preparation of capecitabine that involves the refluxing N4– pentyloxycarbonyl-5-fluorocytosine with trimethylsiloxane, hexamethyl disilazanyl, or sodium iodide with trimethyl chlorosilane in anhydrous acetonitrile, dichloromethane, or toluene, and 5-deoxy-1 ,2,3-tri-O-acetyl-D-ribofuranose, followed by hydrolysis using ammonia/methanol to give capecitabine. The overall process is summarized in Scheme IV.

Scheme IV

International Application Publication No. WO 2007/009303 A1 discloses a method of synthesis for capecitabine, comprising reacting 5′-deoxy-5- fluorocytidine using double (trichloromethyl) carbonate in an inert organic solvent and organic alkali to introduce a protective lactone ring to the hydroxyl of the saccharide moiety; reacting the obtained compound with chloroformate in organic alkali; followed by selective hydrolysis of the sugar component hydrolytic group using an inorganic base to give capecitabine. The overall process is summarized in Scheme V.

Scheme V

Even though all the above documents collectively disclose various processes for the preparation of capecitabine, removal of process-related impurities in the final product has not been adequately addressed. Impurities in any active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) are undesirable, and, in extreme cases, might even be harmful to a patient. Furthermore, the existence of undesired as well as unknown impurities reduces the bioavailability of the API in pharmaceutical products and often decreases the stability and shelf life of a pharmaceutical dosage form.

nmr

1H NMR(CD3OD) δ 0.91(3H5 t), 1.36~1.40(4H, m), 1.41(3H, d), 1.68~1.73(2H, m), 3.72(1H, dd), 4.08(1H, dd), 4.13~4.21(3H, m), 5.7O(1H, s), 7.96(1H, d)

- The acetylation of 5′-deoxy-5-fluorocytidine (I) with acetic anhydride in dry pyridine gives 2′,3′-di-O-acetyl-5′-deoxy-5-fluorocytidine (II), which is condensed with pentyl chloroformate (III) by means of pyridine in dichromethane yielding 2′,3′-di-O-acetyl-5′-deoxy-5-fluoro-N4-(pentyloxycarbonyl)cytidine (IV). Finally, this compound is deacetylated with NaOH in dichloromethane/water. The diacetylated cytidine (II) can also be obtained by condensation of 5-fluorocytosine (V) with 1,2,3-tri-O-acetyl-5-deoxy-beta-D-ribofuranose (VI) by means of trimethylchlorosilane in acetonitrile or HMDS and SnCl4 in dichloromethane..

-

- EP 602454, JP 94211891, US 5472949.

- Capecitabine. Drugs Fut 1996, 21, 4, 358,

- Bioorg Med Chem Lett2000,8,(7):1697,

1-Fe

1-Fe

-Molecular-diagram.jpg)