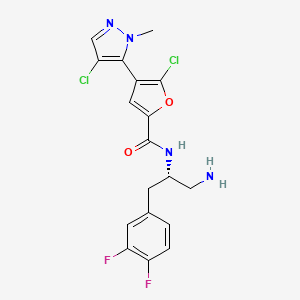

Burixafor is a potent and selective chemokine CXCR4 antagonist developed by TaiGen Biotechnology (www.taigenbiotech.com.tw).

The SDF1/CXCR4 pathway plays key roles in homing and mobilization of hematopoietic stem cells and endothelial progenitor cells. In a mouse model, burixafor efficiently mobilizes stem cells (CD34+) and endothelial progenitor cells (CD133+) from bone marrow into peripheral circulation. It can be used in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, chemotherapy sensitization and other ischemic diseases.

Because TaiGen has filed an IND (CXHL1200371) for burixafor as a chemotherapy sensitizer in October 2012, the new application (CXHL1400844) may supplement a new indication. Phase II clinical trials (NCT02104427) are currently underway in the US, with Phase IIa (NCT01018979, NCT01458288) already completed.

TaiGen plans to initiate clinical trials of burixafor as a chemotherapy sensitizer in China shortly. Burixafor’s annual sales are estimated at $1.1 billion by consultancy company JSB. This compound is protected by patent WO2009131598.

SEE……….http://newdrugapprovals.org/2014/06/09/scinopharm-to-provide-active-pharmaceutical-ingredient-%E8%8B%B1%E6%96%87%E5%90%8D%E7%A7%B0-burixafor-to-ftaigen-for-novel-stem-cell-drug/

英文名称Burixafor

TG-0054

(2-{4-[6-amino-2-({[(1r,4r)-4-({[3-(cyclohexylamino)propyl]amino}methyl)cyclohexyl]methyl}amino)pyrimidin-4-yl]piperazin-1-yl}ethyl)phosphonic acid

[2-[4-[6-Amino-2-[[[trans-4-[[[3-(cyclohexylamino)propyl]amino]methyl]cyclohexyl]methyl]amino]pyrimidin-4-yl]piperazin-1-yl]ethyl]phosphonic acid

1191448-17-5

C27H51N8O3P, 566.7194

chemokine CXCR 4 receptor antagonist;

ScinoPharm to Provide Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient to F*TaiGen for Novel Stem Cell Drug

MarketWatch

The drug has received a Clinical Trial Application from China’s FDA for the initiation of … In addition, six products have entered Phase III clinical trials.

read at

http://www.marketwatch.com/story/scinopharm-to-provide-active-pharmaceutical-ingredient-to-ftaigen-for-novel-stem-cell-drug-2014-06-08

TAINAN, June 8, 2014 — ScinoPharm Taiwan, Ltd. (twse:1789) specializing in the development and manufacture of active pharmaceutical ingredients, and TaiGen Biotechnology (4157.TW; F*TaiGen) jointly announced today the signing of a manufacturing contract for the clinical supply of the API of Burixafor, a new chemical entity discovered and developed by TaiGen. The API will be manufactured in ScinoPharm’s plant in Changshu, China. This cooperation not only demonstrates Taiwan’s international competitive strength in new drug development, but also sees the beginning of a domestic pharmaceutical specialization and cooperation mechanisms, thus establishing a groundbreaking milestone for Taiwan’s pharmaceutical industry.

Dr. Jo Shen, President and CEO of ScinoPharm said, “This cooperation with TaiGen is of representative significance in the domestic pharmaceutical companies’ upstream and downstream cooperation and self-development of new drugs, and indicates the Taiwanese pharmaceutical industry’s cumulative research and development momentum is paving the way forward.” Dr. Jo Shen emphasized, “ScinoPharm’s Changshu Plant provides high-quality API R&D and manufacturing services through its fast, flexible, reliable competitive advantages, effectively assisting clients of new drugs in gaining entry into China, Europe, the United States, and other international markets.”

ScinoPharm President, CEO and Co-Founder Dr. Jo Shen

According to Dr. Ming-Chu Hsu, Chairman and CEO of TaiGen, “R&D is the foundation of the pharmaceutical industry. Once a drug is successfully developed, players at all levels of the value chain could reap the benefit. Burixafor is a 100% in-house developed product that can be used in the treatment of various intractable diseases. The cooperation between TaiGen and ScinoPharm will not only be a win-win for both sides, but will also provide high-quality novel dug for patients from around the world.”

Burixafor is a novel stem cell mobilizer that can efficiently mobilize bone marrow stem cells and tissue precursor cells to the peripheral blood. It can be used in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, chemotherapy sensitization and other ischemic diseases. The results of the ongoing Phase II clinical trial in the United States are very impressive. The drug has received a Clinical Trial Application from China’s FDA for the initiation of a Phase II clinical trial in chemotherapy sensitization under the 1.1 category. According to the pharmaceutical consultancy company JSB, with only stem cell transplant and chemotherapy sensitizer as the indicator, Burixafor’s annual sales are estimated at USD1.1 billion.

ScinoPharm currently has accepted over 80 new drug API process research and development plans, of which five new drugs have been launched in the market. In addition, six products have entered Phase III clinical trials. Through the Changshu Plant’s operation in line with the latest international cGMP plant equipment and quality management standards, the company provides customers with one stop shopping services in professional R&D, manufacturing, and outsourcing, thereby shortening the customer development cycle of customers’ products and accelerating the launch of new products to the market.

TaiGen’s focus is on the research and development of novel drugs. Besides Burixafor, the products also include anti-infective, Taigexyn®, and an anti-hepatitis C drug, TG-2349. Taigexyn® is the first in-house developed novel drug that received new drug application approval from Taiwan’s FDA. TG-2349 is intended for the 160 million global patients with hepatitis C with huge market potential. TaiGen hopes to file one IND with the US FDA every 3-4 years to expand TaiGen’s product line.

About ScinoPharm

ScinoPharm Taiwan, Ltd. is a leading process R&D and API manufacturing service provider to the global pharmaceutical industry. With research and manufacturing facilities in both Taiwan and China, ScinoPharm offers a wide portfolio of services ranging from custom synthesis for early phase pharmaceutical activities to contract services for brand companies as well as APIs for the generic industry. For more information, please visit the Company’s website at http://www.scinopharm.com

About TaiGen Biotechnology

TaiGen Biotechnology is a leading research-based and product-driven biotechnology company in Taiwan with a wholly-owned subsidiary in Beijing, China. The company’s first product, Taigexyn®, have already received NDA approval from Taiwan’s FDA. In addition to Taigexyn®, TaiGen has two other in-house discovered NCEs in clinical development under IND with US FDA: TG-0054, a chemokine receptor antagonist for stem cell transplantation and chemosensitization, in Phase 2 and TG-2349, a HCV protease inhibitor for treatment of chronic hepatitis infection, in Phase 2. Both TG-0054 and TG-2349 are currently in clinical trials in patients in the US.

SOURCE ScinoPharm Taiwan Ltd.

TG-0054 is a potent and selective chemokine CXCR4 (SDF-1) antagonist in phase II clinical studies at TaiGen Biotechnology for use in stem cell transplantation in cancer patients. Specifically, the compound is being developed for the treatment of stem cell transplantation in multiple myeloma, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, Hodgkin’s lymphoma and myocardial ischemia.

Preclinical studies had also been undertaken for the treatment of diabetic retinopathy, critical limb ischemia (CLI) and age-related macular degeneration. In a mouse model, TG-0054 efficiently mobilizes stem cells (CD34+) and endothelial progenitor cells (CD133+) from bone marrow into peripheral circulation.

BACKGROUND

Chemokines are a family of cytokines that regulate the adhesion and transendothelial migration of leukocytes during an immune or inflammatory reaction (Mackay C.R., Nat. Immunol, 2001, 2:95; Olson et al, Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol, 2002, 283 :R7). Chemokines also regulate T cells and B cells trafficking and homing, and contribute to the development of lymphopoietic and hematopoietic systems (Ajuebor et al, Biochem. Pharmacol, 2002, 63:1191). Approximately 50 chemokines have been identified in humans. They can be classified into 4 subfamilies, i.e., CXC, CX3C, CC, and C chemokines, based on the positions of the conserved cysteine residues at the N-terminal (Onuffer et al, Trends Pharmacol ScI, 2002, 23:459). The biological functions of chemokines are mediated by their binding and activation of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) on the cell surface.

Stromal-derived factor- 1 (SDF-I) is a member of CXC chemokines. It is originally cloned from bone marrow stromal cell lines and found to act as a growth factor for progenitor B cells (Nishikawa et al, Eur. J. Immunol, 1988, 18:1767). SDF-I plays key roles in homing and mobilization of hematopoietic stem cells and endothelial progenitor cells (Bleul et al, J. Exp. Med., 1996, 184:1101; and Gazzit et al, Stem Cells, 2004, 22:65-73). The physiological function of SDF-I is mediated by CXCR4 receptor. Mice lacking SDF-I or CXCR4 receptor show lethal abnormality in bone marrow myelopoiesis, B cell lymphopoiesis, and cerebellar development (Nagasawa et al, Nature, 1996, 382:635; Ma et al, Proc. Natl. Acad. ScI, 1998, 95:9448; Zou et al, Nature, 1998, 393:595; Lu et al, Proc. Natl. Acad. ScI, 2002, 99:7090). CXCR4 receptor is expressed broadly in a variety of tissues, particularly in immune and central nervous systems, and has been described as the major co-receptor for HIV- 1/2 on T lymphocytes. Although initial interest in CXCR4 antagonism focused on its potential application to AIDS treatment (Bleul et al, Nature, 1996, 382:829), it is now becoming clear that CXCR4 receptor and SDF-I are also involved in other pathological conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, asthma, and tumor metastases (Buckley et al., J. Immunol., 2000, 165:3423). Recently, it has been reported that a CXCR4 antagonist and an anticancer drug act synergistically in inhibiting cancer such as acute promuelocutic leukemia (Liesveld et al., Leukemia

Research 2007, 31 : 1553). Further, the CXCR4/SDF-1 pathway has been shown to be critically involved in the regeneration of several tissue injury models. Specifically, it has been found that the SDF-I level is elevated at an injured site and CXCR4-positive cells actively participate in the tissue regenerating process.

………………………………………………………………………..

http://www.google.com/patents/WO2009131598A1?cl=en

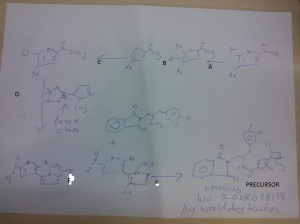

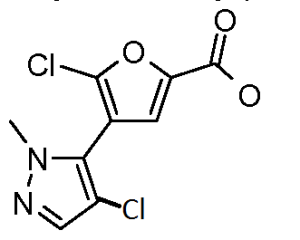

Compound 52

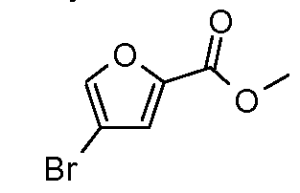

Example 1 : Preparation of Compounds 1

1-1 1-Ii 1-m

^ ^–\\ Λ xCUNN H ‘ ‘22.. P rdu/’C^ ^. , Λ>\V>v

Et3N, TFAA , H_, r [ Y I RRaanneeyy–NNiicckkeell u H f [ Y | NH2

CH2CI2, -10 0C Boc^ ‘NNA/ 11,,44–ddιιooxxaannee B Boocer”1^”–^^ LiOH, H2O, 50 0C

1-IV 1-V

Water (10.0 L) and (BoC)2O (3.33 kgg, 15.3 mol) were added to a solution of trans-4-aminomethyl-cyclohexanecarboxylic acid (compound 1-1, 2.0 kg, 12.7 mol) and sodium bicarbonate (2.67 kg, 31.8 mol). The reaction mixture was stirred at ambient temperature for 18 hours. The aqueous layer was acidified with concentrated hydrochloric acid (2.95 L, pH = 2) and then filtered. The resultant solid was collected, washed three times with water (15 L), and dried in a hot box (60 0C) to give trα/?5-4-(tert-butoxycarbonylamino-methyl)-cyclo-hexanecarboxylic acid (Compound l-II, 3.17 kg, 97%) as a white solid. Rf = 0.58 (EtOAc). LC-MS m/e 280 (M+Na+). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 4.58 (brs, IH), 2.98 (t, J= 6.3 Hz, 2H), 2.25 (td, J = 12, 3.3 Hz, IH), 2.04 (d, J= 11.1 Hz, 2H), 1.83 (d, J= 11.1 Hz, 2H), 1.44 (s, 9H), 1.35-1.50 (m, 3H), 0.89-1.03 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 181.31, 156.08, 79.12, 46.41, 42.99, 37.57, 29.47, 28.29, 27.96. M.p. 134.8-135.0 0C. A suspension of compound l-II (1.0 kg, 3.89 mol) in THF (5 L) was cooled at

-10 0C and triethyl amine (1.076 L, 7.78 mol) and ethyl chloroformate (0.441 L, 4.47 mol) were added below -10 0C. The reaction mixture was stirred at ambient temperature for 3 hours. The reaction mixture was then cooled at -100C again and NH4OH (3.6 L, 23.34 mol) was added below -10 0C. The reaction mixture was stirred at ambient temperature for 18 hours and filtered. The solid was collected and washed three times with water (10 L) and dried in a hot box (6O0C) to give trans-4- (tert-butoxycarbonyl-amino-methyl)-cyclohexanecarboxylic acid amide (Compound l-III, 0.8 kg, 80%) as a white solid. Rf= 0.23 (EtOAc). LC-MS m/e 279, M+Na+. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CD3OD) δ 6.63 (brs, IH), 2.89 (t, J= 6.3 Hz, 2H), 2.16 (td, J = 12.2, 3.3 Hz, IH), 1.80-1.89 (m, 4H), 1.43 (s, 9H), 1.37-1.51 (m, 3H), 0.90-1.05 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CD3OD) δ 182.26, 158.85, 79.97, 47.65, 46.02, 39.28, 31.11, 30.41, 28.93. M.p. 221.6-222.0 0C.

A suspension of compound l-III (1.2 kg, 4.68 mol) in CH2Cl2 (8 L) was cooled at -1O0C and triethyl amine (1.3 L, 9.36 mol) and trifluoroacetic anhydride (0.717 L, 5.16 mol) were added below -10 0C. The reaction mixture was stirred for 3 hours. After water (2.0 L) was added, the organic layer was separated and washed with water (3.0 L) twice. The organic layer was then passed through silica gel and concentrated. The resultant oil was crystallized by methylene chloride. The crystals were washed with hexane to give £rαns-(4-cyano-cyclohexylmethyl)-carbamic acid tert-butyl ester (Compound 1-IV, 0.95 kg, 85%) as a white crystal. Rf = 0.78 (EtOAc). LC-MS m/e 261, M+Na+. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 4.58 (brs, IH), 2.96 (t, J = 6.3 Hz, 2H), 2.36 (td, J= 12, 3.3 Hz, IH), 2.12 (dd, J= 13.3, 3.3 Hz, 2H), 1.83 (dd, J = 13.8, 2.7 Hz, 2H), 1.42 (s, 9H), 1.47-1.63 (m, 3H), 0.88-1.02 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 155.96, 122.41, 79.09, 45.89, 36.92, 29.06, 28.80, 28.25, 28.00. M.p. 100.4~100.6°C.

Compound 1-IV (1.0 kg, 4.196 mol) was dissolved in a mixture of 1 ,4-dioxane (8.0 L) and water (2.0 L). To the reaction mixture were added lithium hydroxide monohydrate (0.314 kg, 4.191), Raney-nickel (0.4 kg, 2.334 mol), and 10% palladium on carbon (0.46 kg, 0.216 mol) as a 50% suspension in water. The reaction mixture was stirred under hydrogen atmosphere at 5O0C for 20 hours. After the catalysts were removed by filtration and the solvents were removed in vacuum, a mixture of water (1.0 L) and CH2Cl2 (0.3 L) was added. After phase separation, the organic phase was washed with water (1.0 L) and concentrated to give £rα/?s-(4-aminomethyl- cyclohexylmethyl)-carbamic acid tert- butyl ester (compound 1-V, 0.97 kg, 95%) as pale yellow thick oil. Rf = 0.20 (MeOH/EtOAc = 9/1). LC-MS m/e 243, M+H+. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 4.67 (brs, IH), 2.93 (t, J= 6.3 Hz, 2H), 2.48 (d, J= 6.3 Hz, 2H), 1.73-1.78 (m, 4H), 1.40 (s, 9H), 1.35 (brs, 3H), 1.19-1.21 (m, IH), 0.77-0.97 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 155.85, 78.33, 48.27, 46.38, 40.80, 38.19, 29.87, 29.76, 28.07. A solution of compound 1-V (806 g) and Et3N (1010 g, 3 eq) in 1-pentanol

(2.7 L) was treated with compound 1-VI, 540 g, 1 eq) at 900C for 15 hours. TLC showed that the reaction was completed. Ethyl acetate (1.5 L) was added to the reaction mixture at 25°C. The solution was stirred for 1 hour. The Et3NHCl salt was filtered. The filtrate was then concentrated to 1.5 L (1/6 of original volume) by vacuum at 500C. Then, diethyl ether (2.5 L) was added to the concentrated solution to afford the desired product 1-VII (841 g, 68% yield) after filtration at 250C .

A solution of intermediate 1-VII (841 g) was treated with 4 N HCl/dioxane (2.7 L) in MeOH (8.1 L) and stirred at 25°C for 15 hours. TLC showed that the reaction was completed. The mixture was concentrated to 1.5 L (1/7 of original volume) by vacuum at 500C. Then, diethyl ether (5 L) was added to the solution slowly, and HCl salt of 1-VIII (774 g) was formed, filtered, and dried under vacuum (<10 torr). For neutralization, K2CO3 (2.5 kg, 8 eq) was added to the solution of HCl salt of 1-VIII in MeOH (17 L) at 25°C. The mixture was stirred at the same temperature for 3 hours (pH > 12) and filtered (estimated amount of 1-VIII in the filtrate is 504 g). Aldehyde 1-IX (581 g, 1.0 eq based on mole of 1-VII) was added to the filtrate of 1-VIII at 0-100C. The reaction was stirred at 0-100C for 3 hours. TLC showed that the reaction was completed. Then, NaBH4 (81 g, 1.0 eq based on mole of 1-VII) was added at less than 100C and the solution was stirred at 10-150C for Ih. The solution was concentrated to get a residue, which then treated with CH2Cl2 (15 L). The mixture was washed with saturated aq. NH4Cl solution (300 mL) diluted with H2O (1.2 L). The CH2Cl2 layer was concentrated and the residue was purified by chromatography on silica gel (short column, EtOAc as mobile phase for removing other components; MeOH/28% NH4OH = 97/3 as mobile phase for collecting 1-X) afforded crude 1-X (841 g). Then Et3N (167 g, leq) and BoC2O (360 g, leq) were added to the solution of

1-X (841 g) in CH2Cl2 (8.4 L) at 25°C. The mixture was stirred at 25°C for 15 hours. After the reaction was completed as evidenced by TLC, the solution was concentrated and EtOAc (5 L) was added to the resultant residue. The solution was concentrated to 3L (1/2 of the original volume) under low pressure at 500C. Then, n-hexane (3 L) was added to the concentrated solution. The solid product formed at 500C by seeding to afford the desired crude product 1-XI (600 g, 60% yield) after filtration and evaporation. To compound 1-XI (120.0 g) and piperazine (1-XII, 50.0 g, 3 eq) in 1- pentanol (360 niL) was added Et3N (60.0 g, 3.0 eq) at 25°C. The mixture was stirred at 1200C for 8 hours. Ethyl acetate (480 mL) was added to the reaction mixture at 25°C. The solution was stirred for Ih. The Et3NHCl salt was filtered and the solution was concentrated and purified by silica gel (EtOAc/MeOH = 2:8) to afforded 1-XIII (96 g) in a 74% yield.

A solution of intermediate 1-XIII (100 mg) was treated with 4 N HCl/dioxane (2 mL) in CH2Cl2 (1 mL) and stirred at 25°C for 15 hours. The mixture was concentrated to give hydrochloride salt of compound 1 (51 mg). CI-MS (M+ + 1): 459.4

Example 2: Preparation of Compound 2

Compound 2 Intermediate 1-XIII was prepared as described in Example 1.

To a solution of 1-XIII (120 g) in MeOH (2.4 L) were added diethyl vinyl phosphonate (2-1, 45 g, 1.5 eq) at 25°C. The mixture was stirred under 65°C for 24 hours. TLC and HPLC showed that the reaction was completed. The solution was concentrated and purified by silica gel (MeOH/CH2Cl2 = 8/92) to get 87 g of 2-11 (53% yield, purity > 98%, each single impurity <1%) after analyzing the purity of the product by HPLC.

A solution of 20% TFA/CH2C12 (36 mL) was added to a solution of intermediate 2-11 (1.8 g) in CH2Cl2 (5 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred for 15 hours at room temperature and concentrated by removing the solvent to afford trifluoracetic acid salt of compound 2 (1.3 g). CI-MS (M+ + 1): 623.1

Example 3 : Preparation of Compound 3

TMSBr H H

s U

Intermediate 2-11 was prepared as described in Example 2. To a solution of 2-11 (300 g) in CH2Cl2 (1800 mL) was added TMSBr (450 g, 8 eq) at 10-150C for 1 hour. The mixture was stirred at 25°C for 15 hours. The solution was concentrated to remove TMSBr and solvent under vacuum at 400C.

CH2Cl2 was added to the mixture to dissolve the residue. TMSBr and solvent were removed under vacuum again to obtain 36O g crude solid after drying under vacuum (<1 torr) for 3 hours. Then, the crude solid was washed with 7.5 L IPA/MeOH (9/1) to afford compound 3 (280 g) after filtration and drying at 25°C under vacuum (<1 torr) for 3 hours. Crystallization by EtOH gave hydrobromide salt of compound 3 (19Og). CI-MS (M+ + 1): 567.0.

The hydrobromide salt of compound 3 (5.27 g) was dissolved in 20 mL water and treated with concentrated aqueous ammonia (pH=9-10), and the mixture was evaporated in vacuo. The residue in water (30 mL) was applied onto a column (100 mL, 4.5×8 cm) of Dowex 50WX8 (H+ form, 100-200 mesh) and eluted (elution rate, 6 mL/min). Elution was performed with water (2000 mL) and then with 0.2 M aqueous ammonia. The UV-absorbing ammonia eluate was evaporated to dryness to afford ammonia salt of compound 3 (2.41 g). CI-MS (M+ + 1): 567.3.

The ammonia salt of compound 3 (1.5 g) was dissolved in water (8 mL) and alkalified with concentrated aqueous ammonia (pH=l 1), and the mixture solution was applied onto a column (75 mL, 3×14 cm) of Dowex 1X2 (acetate form, 100-200 mesh) and eluted (elution rate, 3 mL/min). Elution was performed with water (900 mL) and then with 0.1 M acetic acid. The UV-absorbing acetic acid eluate was evaporated, and the residue was codistilled with water (5×50 mL) to afford compound 3 (1.44 g). CI-MS (M+ + 1): 567.4. Example 4: Preparation of Compound 4

Compound 4

Intermediate 1-XIII was obtained during the preparation of compound 1. To a solution of diethyl vinyl phosphonate (4-1, 4 g) in CH2Cl2 (120 mL) was added oxalyl chloride (15.5 g, 5 eq) and the mixture was stirred at 300C for 36 hours. The mixture were concentrated under vacuum on a rotatory evaporated to give quantitatively the corresponding phosphochloridate, which was added to a mixture of cyclohexyl amine (4-II, 5.3 g, 2.2 eq), CH2Cl2 (40 mL), and Et3N (6.2 g, 2.5 eq). The mixture was stirred at 35°C for 36 hours, and then was washed with water. The organic layer was dried (MgSO4), filtered, and evaporated to afford 4-III (4.7 g, 85% yield) as brown oil.

Compound 4-III (505 mg) was added to a solution of intermediate 1-XIII (500 mg) in MeOH (4 mL). The solution was stirred at 45°C for 24 hours. The solution was concentrated and the residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (EtOAc/ MeOH = 4: 1) to afford intermediate 4-IV (420 mg) in a 63% yield.

A solution of HCl in ether (5 mL) was added to a solution of intermediate 4- IV (420 mg) in CH2Cl2 (1.0 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred for 12 hours at room temperature and concentrated by removing the solvent. The resultant residue was washed with ether to afford hydrochloride salt of compound 4 (214 mg). CI-MS (M+ + 1): 595.1

Preparation of compound 51

TMSBr

Intermediate l-II was prepared as described in Example 1. To a suspension of the intermediate l-II (31.9 g) in toluene (150 mL) were added phosphorazidic acid diphenyl ester (51-1, 32.4 g) and Et3N (11.9 g) at 25°C for 1 hour. The reaction mixture was stirred at 800C for 3 hours and then cooled to 25°C. After benzyl alcohol (51-11, 20 g) was added, the reaction mixture was stirred at 800C for additional 3 hours and then warmed to 1200C overnight. It was then concentrated and dissolved again in EtOAc and H2O. The organic layer was collected. The aqueous layer was extracted with EtOAc. The combined organic layers were washed with 2.5 N HCl, saturated aqueous NaHCO3 and brine, dried over anhydrous MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated. The residue thus obtained was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (EtOAc/Hexane = 1 :2) to give Intermediate 51-111 (35 g) in a 79% yield. A solution of intermediate 51-111 (35 g) treated with 4 N HCl/dioxane (210 rnL) in MeOH (350 mL) was stirred at room temperature overnight. After ether (700 mL) was added, the solution was filtered. The solid was dried under vacuum. K2CO3 was added to a suspension of this solid in CH3CN and ώo-propanol at room temperature for 10 minutes. After water was added, the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2 hours, filtered, dried over anhydrous MgSO4, and concentrated. The resultant residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (using CH2Cl2 and MeOH as an eluant) to give intermediate 51-IV (19 g) in a 76% yield. Intermediate 1-IX (21 g) was added to a solution of intermediate 51-IV (19 g) in CH2Cl2 (570 mL). The mixture was stirred at 25°C for 2 hours. NaBH(OAc)3 (23 g) was then added at 25°C overnight. After the solution was concentrated, a saturated aqueous NaHCO3solution was added to the resultant residue. The mixture was then extracted with CH2Cl2. The solution was concentrated and the residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (using EtOAc and MeOH as an eluant) to afford intermediate 51-V (23.9 g) in a 66% yield.

A solution of intermediate 51-V (23.9 g) and BoC2O (11.4 g) in CH2Cl2 (200 mL) was added to Et3N (5.8 mL) at 25°C for overnight. The solution was then concentrated and the resultant residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (using EtOAc and Hexane as an eluant) to give intermediate 51-VI (22 g) in a 77% yield.

10% Pd/C (2.2 g) was added to a suspension of intermediate 51-VI (22 g) in MeOH (44 mL). The mixture was stirred at ambient temperature under hydrogen atmosphere overnight, filtered, and concentrated. The residue thus obtained was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (using EtOAc and MeOH as an eluant) to afford intermediate 51-VII (16.5 g) in a 97% yield.

Intermediate 51-VII (16.5 g) and Et3N (4.4 mL) in 1-pentanol (75 mL) was allowed to react with 2,4-dichloro-6-aminopyrimidine (1-VI, 21 g) at 1200C overnight. The solvent was then removed and the residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (using EtOAc and hexane as an eluant) to afford intermediate 51-VIII (16.2 g) in a 77% yield.

A solution of intermediate 51-VIII (16.2 g) and piperazine (1-XII, 11.7 g) in 1-pentanol (32 mL) was added to Et3N (3.3 mL) at 1200C overnight. After the solution was concentrated, the residue was treated with water and extracted with CH2Cl2. The organic layer was collected and concentrated. The residue thus obtained was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (using EtOAc/ MeOH to 28% NH40H/Me0H as an eluant) to afford Intermediate 51-IX (13.2 g) in a 75% yield. Diethyl vinyl phosphonate (2-1) was treated with 51-IX as described in

Example 3 to afford hydrobromide salt of compound 51. CI-MS (M+ + 1): 553.3

………………………………….

Preparation of Compound 1

Water (10.0 L) and (Boc)2O (3.33 kgg, 15.3 mol) were added to a solution of trans-4-aminomethyl-cyclohexanecarboxylic acid (compound 1-I, 2.0 kg, 12.7 mol) and sodium bicarbonate (2.67 kg, 31.8 mol). The reaction mixture was stirred at ambient temperature for 18 hours. The aqueous layer was acidified with concentrated hydrochloric acid (2.95 L, pH=2) and then filtered. The resultant solid was collected, washed three times with water (15 L), and dried in a hot box (60° C.) to give trans-4-(tert-butoxycarbonylamino-methyl)-cyclo-hexanecarboxylic acid (Compound 1-II, 3.17 kg, 97%) as a white solid. Rf=0.58 (EtOAc). LC-MS m/e 280 (M+Na+). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 4.58 (brs, 1H), 2.98 (t, J=6.3 Hz, 2H), 2.25 (td, J=12, 3.3 Hz, 1H), 2.04 (d, J=11.1 Hz, 2H), 1.83 (d, J=11.1 Hz, 2H), 1.44 (s, 9H), 1.35˜1.50 (m, 3H), 0.89˜1.03 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 181.31, 156.08, 79.12, 46.41, 42.99, 37.57, 29.47, 28.29, 27.96. M.p. 134.8˜135.0° C.

A suspension of compound 1-II (1.0 kg, 3.89 mol) in THF (5 L) was cooled at 10° C. and triethyl amine (1.076 L, 7.78 mol) and ethyl chloroformate (0.441 L, 4.47 mol) were added below 10° C. The reaction mixture was stirred at ambient temperature for 3 hours. The reaction mixture was then cooled at 10° C. again and NH4OH (3.6 L, 23.34 mol) was added below 10° C. The reaction mixture was stirred at ambient temperature for 18 hours and filtered. The solid was collected and washed three times with water (10 L) and dried in a hot box (60° C.) to give trans-4-(tert-butoxycarbonyl-amino-methyl)-cyclohexanecarboxylic acid amide (Compound 1-III, 0.8 kg, 80%) as a white solid. Rf=0.23 (EtOAc). LC-MS m/e 279, M+Na+. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CD3OD) δ 6.63 (brs, 1H), 2.89 (t, J=6.3 Hz, 2H), 2.16 (td, J=12.2, 3.3 Hz, 1H), 1.80˜1.89 (m, 4H), 1.43 (s, 9H), 1.37˜1.51 (m, 3H), 0.90˜1.05 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CD3OD) δ 182.26, 158.85, 79.97, 47.65, 46.02, 39.28, 31.11, 30.41, 28.93. M.p. 221.6˜222.0° C.

A suspension of compound 1-III (1.2 kg, 4.68 mol) in CH2Cl2 (8 L) was cooled at 10° C. and triethyl amine (1.3 L, 9.36 mol) and trifluoroacetic anhydride (0.717 L, 5.16 mol) were added below 10° C. The reaction mixture was stirred for 3 hours. After water (2.0 L) was added, the organic layer was separated and washed with water (3.0 L) twice. The organic layer was then passed through silica gel and concentrated. The resultant oil was crystallized by methylene chloride. The crystals were washed with hexane to give trans-(4-cyano-cyclohexylmethyl)-carbamic acid tent-butyl ester (Compound 1-IV, 0.95 kg, 85%) as a white crystal. Rf=0.78 (EtOAc). LC-MS m/e 261, M+Na+. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 4.58 (brs, 1H), 2.96 (t, J=6.3 Hz, 2H), 2.36 (td, J=12, 3.3 Hz, 1H), 2.12 (dd, J=13.3, 3.3 Hz, 2H), 1.83 (dd, J=13.8, 2.7 Hz, 2H), 1.42 (s, 9H), 1.47˜1.63 (m, 3H), 0.88˜1.02 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 155.96, 122.41, 79.09, 45.89, 36.92, 29.06, 28.80, 28.25, 28.00. M.p. 100.4˜100.6° C.

Compound 1-IV (1.0 kg, 4.196 mol) was dissolved in a mixture of 1,4-dioxane (8.0 L) and water (2.0 L). To the reaction mixture were added lithium hydroxide monohydrate (0.314 kg, 4.191), Raney-nickel (0.4 kg, 2.334 mol), and 10% palladium on carbon (0.46 kg, 0.216 mol) as a 50% suspension in water. The reaction mixture was stirred under hydrogen atmosphere at 50° C. for 20 hours. After the catalysts were removed by filtration and the solvents were removed in vacuum, a mixture of water (1.0 L) and CH2Cl2 (0.3 L) was added. After phase separation, the organic phase was washed with water (1.0 L) and concentrated to give trans-(4-aminomethyl-cyclohexylmethyl)-carbamic acid tert-butyl ester (compound 1-V, 0.97 kg, 95%) as pale yellow thick oil. Rf=0.20 (MeOH/EtOAc=9/1). LC-MS m/e 243, M+H+. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 4.67 (brs, 1H), 2.93 (t, J=6.3 Hz, 2H), 2.48 (d, J=6.3 Hz, 2H), 1.73˜1.78 (m, 4H), 1.40 (s, 9H), 1.35 (brs, 3H), 1.19˜1.21 (m, 1H), 0.77˜0.97 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 155.85, 78.33, 48.27, 46.38, 40.80, 38.19, 29.87, 29.76, 28.07.

A solution of compound 1-V (806 g) and Et3N (1010 g, 3 eq) in 1-pentanol (2.7 L) was treated with compound 1-VI, 540 g, 1 eq) at 90° C. for 15 hours. TLC showed that the reaction was completed.

Ethyl acetate (1.5 L) was added to the reaction mixture at 25° C. The solution was stirred for 1 hour. The Et3NHCl salt was filtered. The filtrate was then concentrated to 1.5 L (1/6 of original volume) by vacuum at 50° C. Then, diethyl ether (2.5 L) was added to the concentrated solution to afford the desired product 1-VII (841 g, 68% yield) after filtration at 25° C.

A solution of intermediate 1-VII (841 g) was treated with 4 N HCl/dioxane (2.7 L) in MeOH (8.1 L) and stirred at 25° C. for 15 hours. TLC showed that the reaction was completed. The mixture was concentrated to 1.5 L (1/7 of original volume) by vacuum at 50° C. Then, diethyl ether (5 L) was added to the solution slowly, and HCl salt of 1-VIII (774 g) was formed, filtered, and dried under vacuum (<10 ton). For neutralization, K2CO3 (2.5 kg, 8 eq) was added to the solution of HCl salt of 1-VIII in MeOH (17 L) at 25° C. The mixture was stirred at the same temperature for 3 hours (pH>12) and filtered (estimated amount of 1-VIII in the filtrate is 504 g).

Aldehyde 1-IX (581 g, 1.0 eq based on mole of 1-VII) was added to the filtrate of 1-VIII at 0-10° C. The reaction was stirred at 0-10° C. for 3 hours. TLC showed that the reaction was completed. Then, NaBH4 (81 g, 1.0 eq based on mole of 1-VII) was added at less than 10° C. and the solution was stirred at 10-15° C. for 1 h. The solution was concentrated to get a residue, which then treated with CH2Cl2 (15 L). The mixture was washed with saturated aq. NH4Cl solution (300 mL) diluted with H2O (1.2 L). The CH2Cl2 layer was concentrated and the residue was purified by chromatography on silica gel (short column, EtOAc as mobile phase for removing other components; MeOH/28% NH4OH=97/3 as mobile phase for collecting 1-X) afforded crude 1-X (841 g).

Then Et3N (167 g, 1 eq) and Boc2O (360 g, 1 eq) were added to the solution of 1-X (841 g) in CH2Cl2 (8.4 L) at 25° C. The mixture was stirred at 25° C. for 15 hours. After the reaction was completed as evidenced by TLC, the solution was concentrated and EtOAc (5 L) was added to the resultant residue. The solution was concentrated to 3 L (1/2 of the original volume) under low pressure at 50° C. Then, n-hexane (3 L) was added to the concentrated solution. The solid product formed at 50° C. by seeding to afford the desired crude product 1-XI (600 g, 60% yield) after filtration and evaporation.

To compound 1-XI (120.0 g) and piperazine (1-XII, 50.0 g, 3 eq) in 1-pentanol (360 mL) was added Et3N (60.0 g, 3.0 eq) at 25° C. The mixture was stirred at 120° C. for 8 hours. Ethyl acetate (480 mL) was added to the reaction mixture at 25° C. The solution was stirred for 1 h. The Et3NHCl salt was filtered and the solution was concentrated and purified by silica gel (EtOAc/MeOH=2:8) to afforded 1-XIII (96 g) in a 74% yield.

To a solution of 1-XIII (120 g) in MeOH (2.4 L) were added diethyl vinyl phosphonate (1-XIV, 45 g, 1.5 eq) at 25° C. The mixture was stirred under 65° C. for 24 hours. TLC and HPLC showed that the reaction was completed. The solution was concentrated and purified by silica gel (MeOH/CH2Cl2=8/92) to get 87 g of 1-XV (53% yield, purity>98%, each single impurity<1%) after analyzing the purity of the product by HPLC.

A solution of 20% TFA/CH2Cl2 (36 mL) was added to a solution of intermediate 1-XV (1.8 g) in CH2Cl2 (5 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred for 15 hours at room temperature and concentrated by removing the solvent to afford trifluoracetic acid salt of compound 1 (1.3 g).

CI-MS (M++1): 623.1.

(2) Preparation of Compound 2

Intermediate 1-XV was prepared as described in Example 1.

To a solution of 1-XV (300 g) in CH2Cl2 (1800 mL) was added TMSBr (450 g, 8 eq) at 10-15° C. for 1 hour. The mixture was stirred at 25° C. for 15 hours. The solution was concentrated to remove TMSBr and solvent under vacuum at 40° C. CH2Cl2 was added to the mixture to dissolve the residue. TMSBr and solvent were removed under vacuum again to obtain 360 g crude solid after drying under vacuum (<1 torr) for 3 hours. Then, the crude solid was washed with 7.5 L IPA/MeOH (9/1) to afford compound 2 (280 g) after filtration and drying at 25° C. under vacuum (<1 ton) for 3 hours. Crystallization by EtOH gave hydrobromide salt of compound 2 (190 g). CI-MS (M++1): 567.0.

The hydrobromide salt of compound 2 (5.27 g) was dissolved in 20 mL water and treated with concentrated aqueous ammonia (pH=9-10), and the mixture was evaporated in vacuo. The residue in water (30 mL) was applied onto a column (100 mL, 4.5×8 cm) of Dowex 50WX8 (H+ form, 100-200 mesh) and eluted (elution rate, 6 mL/min). Elution was performed with water (2000 mL) and then with 0.2 M aqueous ammonia. The UV-absorbing ammonia eluate was evaporated to dryness to afford ammonia salt of compound 2 (2.41 g). CI-MS (M++1): 567.3.

The ammonia salt of compound 2 (1.5 g) was dissolved in water (8 mL) and alkalified with concentrated aqueous ammonia (pH=11), and the mixture solution was applied onto a column (75 mL, 3×14 cm) of Dowex 1×2 (acetate form, 100-200 mesh) and eluted (elution rate, 3 mL/min). Elution was performed with water (900 mL) and then with 0.1 M acetic acid. The UV-absorbing acetic acid eluate was evaporated, and the residue was codistilled with water (5×50 mL) to afford compound 2 (1.44 g). CI-MS (M++1): 567.4.

(3) Preparation of Compound 3

Intermediate 1-XIII was obtained during the preparation of compound 1.

To a solution of diethyl vinyl phosphonate (3-I, 4 g) in CH2Cl2 (120 mL) was added oxalyl chloride (15.5 g, 5 eq) and the mixture was stirred at 30° C. for 36 hours. The mixture were concentrated under vacuum on a rotatory evaporated to give quantitatively the corresponding phosphochloridate, which was added to a mixture of cyclohexyl amine (3-II, 5.3 g, 2.2 eq), CH2Cl2 (40 mL), and Et3N (6.2 g, 2.5 eq). The mixture was stirred at 35° C. for 36 hours, and then was washed with water. The organic layer was dried (MgSO4), filtered, and evaporated to afford 3-III (4.7 g, 85% yield) as brown oil.

Compound 3-III (505 mg) was added to a solution of intermediate 1-XIII (500 mg) in MeOH (4 mL). The solution was stirred at 45° C. for 24 hours. The solution was concentrated and the residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (EtOAc/MeOH=4:1) to afford intermediate 3-IV (420 mg) in a 63% yield.

A solution of HCl in ether (5 mL) was added to a solution of intermediate 3-IV (420 mg) in CH2Cl2 (1.0 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred for 12 hours at room temperature and concentrated by removing the solvent. The resultant residue was washed with ether to afford hydrochloride salt of compound 3 (214 mg).

CI-MS (M++1): 595.1.

(4) Preparation of Compound 4

Compound 4 was prepared in the same manner as that described in Example 2 except that sodium 2-bromoethanesulfonate in the presence of Et3N in DMF at 45° C. was used instead of diethyl vinyl phosphonate. Deportations of amino-protecting group by hydrochloride to afford hydrochloride salt of compound 4.

CI-MS (M++1): 567.3

(5) Preparation of Compound 5

Compound 5 was prepared in the same manner as that described in Example 2 except that diethyl-1-bromopropylphosphonate in the presence of K2CO3 in CH3CN was used instead of diethyl vinyl phosphonate.

CI-MS (M++1): 581.4

(6) Preparation of Compound 6

Compound 6 was prepared in the same manner as that described in Example 5 except that 1,4-diaza-spiro[5.5]undecane dihydrochloride was used instead of piperazine.

CI-MS (M++1): 649.5

(7) Preparation of Compound 7

Intermediate 1-II was prepared as described in Example 1.

To a suspension of the intermediate 1-II (31.9 g) in toluene (150 mL) were added phosphorazidic acid diphenyl ester (7-I, 32.4 g) and Et3N (11.9 g) at 25° C. for 1 hour. The reaction mixture was stirred at 80° C. for 3 hours and then cooled to 25° C. After benzyl alcohol (7-II, 20 g) was added, the reaction mixture was stirred at 80° C. for additional 3 hours and then warmed to 120° C. overnight. It was then concentrated and dissolved again in EtOAc and H2O. The organic layer was collected. The aqueous layer was extracted with EtOAc. The combined organic layers were washed with 2.5 N HCl, saturated aqueous NaHCO3 and brine, dried over anhydrous MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated. The residue thus obtained was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (EtOAc/Hexane=1:2) to give Intermediate 7-III (35 g) in a 79% yield.

A solution of intermediate 7-III (35 g) treated with 4 N HCl/dioxane (210 mL) in MeOH (350 mL) was stirred at room temperature overnight. After ether (700 mL) was added, the solution was filtered. The solid was dried under vacuum. K2CO3 was added to a suspension of this solid in CH3CN and iso-propanol at room temperature for 10 minutes. After water was added, the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2 hours, filtered, dried over anhydrous MgSO4, and concentrated. The resultant residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (using CH2Cl2 and MeOH as an eluant) to give intermediate 7-IV (19 g) in a 76% yield.

Intermediate 1-IX (21 g) was added to a solution of intermediate 7-IV (19 g) in CH2Cl2 (570 mL). The mixture was stirred at 25° C. for 2 hours. NaBH(OAc)3(23 g) was then added at 25° C. overnight. After the solution was concentrated, a saturated aqueous NaHCO3 solution was added to the resultant residue. The mixture was then extracted with CH2Cl2. The solution was concentrated and the residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (using EtOAc and MeOH as an eluant) to afford intermediate 7-V (23.9 g) in a 66% yield.

A solution of intermediate 7-V (23.9 g) and Boc2O (11.4 g) in CH2Cl2 (200 mL) was added to Et3N (5.8 mL) at 25° C. for overnight. The solution was then concentrated and the resultant residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (using EtOAc and Hexane as an eluant) to give intermediate 7-VI (22 g) in a 77% yield. 10% Pd/C (2.2 g) was added to a suspension of intermediate 7-VI (22 g) in MeOH (44 mL). The mixture was stirred at ambient temperature under hydrogen atmosphere overnight, filtered, and concentrated. The residue thus obtained was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (using EtOAc and MeOH as an eluant) to afford intermediate 7-VII (16.5 g) in a 97% yield.

Intermediate 7-VII (16.5 g) and Et3N (4.4 mL) in 1-pentanol (75 mL) was allowed to react with 2,4-dichloro-6-aminopyrimidine (1-VI, 21 g) at 120° C. overnight. The solvent was then removed and the residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (using EtOAc and hexane as an eluant) to afford intermediate 7-VIII (16.2 g) in a 77% yield.

A solution of intermediate 7-VIII (16.2 g) and piperazine (1-XII, 11.7 g) in 1-pentanol (32 mL) was added to Et3N (3.3 mL) at 120° C. overnight. After the solution was concentrated, the residue was treated with water and extracted with CH2Cl2. The organic layer was collected and concentrated. The residue thus obtained was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (using EtOAc/MeOH to 28% NH4OH/MeOH as an eluant) to afford Intermediate 7-IX (13.2 g) in a 75% yield.

Diethyl vinyl phosphonate (2-I) was treated with 7-IX as described in Example 3 to afford hydrobromide salt of compound 7.

CI-MS (M++1): 553.3

(8) Preparation of Compound 8

Cis-1,4-cyclohexanedicarboxylic acid (8-I, 10 g) in THF (100 ml) was added oxalyl chloride (8-II, 15.5 g) at 0° C. and then DMF (few drops). The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 15 hours. The solution was concentrated and the residue was dissolved in THF (100 ml). The mixture solution was added to ammonium hydroxide (80 ml) and stirred for 1 hour. The solution was concentrated and filtration to afford crude product 8-III (7.7 g).

Compound 8-III (7.7 g) in THF (200 ml) was slowly added to LiAlH4 (8.6 g) in THF (200 ml) solution at 0° C. The mixture solution was stirred at 65° C. for 15 hours. NaSO4.10H2O was added at room temperature and stirred for 1 hours. The resultant mixture was filtered to get filtrate and concentrated. The residue was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (100 ml). Et3N (27 g) and (Boc)2O (10 g) were added at room temperature. The solution was stirred for 15 h, and then concentrated to get resultant residue. Ether was added to the resultant residue. Filtration and drying under vacuum afforded solid crude product 8-IV (8.8 g).

A solution of compound 8-IV (1.1 g) and Et3N (1.7 g) in 1-pentanol (10 ml) was reacted with 2,4-dichloro-6-aminopyrimidine (1-VI, 910 mg) at 90° C. for 15 hours. TLC showed that the reaction was completed. Ethyl acetate (10 mL) was added to the reaction mixture at 25° C. The solution was stirred for 1 hour. The Et3NHCl salt was removed. The filtrate was concentrated and purified by silica gel (EtOAc/Hex=1:2) to afford the desired product 8-V (1.1 g, 65% yield).

A solution of intermediate 8-V (1.1 g) was treated with 4 N HCl/dioxane (10 ml) in MeOH (10 ml) and stirred at 25° C. for 15 hours. TLC showed that the reaction was completed. The mixture was concentrated, filtered, and dried under vacuum (<10 ton). For neutralization, K2CO3 (3.2 g) was added to the solution of HCl salt in MeOH (20 ml) at 25° C. The mixture was stirred at the same temperature for 3 hours (pH>12) and filtered. Aldehyde 1-IX (759 mg) was added to the filtrate at 0-10° C. The reaction was stirred at 0-10° C. for 3 hours. TLC showed that the reaction was completed. Then, NaBH4 (112 mg) was added at less than 10° C. and the solution was stirred at 10-15° C. for 1 hour. The solution was concentrated to get a residue, which was then treated with CH2Cl2 (10 mL). The mixture was washed with saturated NH4Cl (aq) solution. The CH2Cl2 layer was concentrated and the residue was purified by chromatography on silica gel (MeOH/28% NH4OH=97/3) to afford intermediate 8-VI (1.0 g, 66% yield).

Et3N (600 mg) and Boc2O (428 mg) were added to the solution of 8-VI (1.0 g) in CH2Cl2 (10 ml) at 25° C. The mixture was stirred at 25° C. for 15 hours. TLC showed that the reaction was completed. The solution was concentrated and purified by chromatography on silica gel (EtOAc/Hex=1:1) to afford intermediate 8-VII (720 mg, 60% yield).

To a solution compound 8-VII (720 mg) and piperazine (1-XII, 1.22 g) in 1-pentanol (10 mL) was added Et3N (1.43 g) at 25° C. The mixture was stirred at 120° C. for 24 hours. TLC showed that the reaction was completed. Ethyl acetate (20 mL) was added at 25° C. The solution was stirred for 1 hour. The Et3NHCl salt was removed and the solution was concentrated and purified by silica gel (EtOAc/MeOH=2:8) to afford 8-VIII (537 mg) in 69% yield.

To a solution of 8-VIII (537 mg) in MeOH (11 ml) was added diethyl vinyl phosphonate (2-I, 201 mg) at 25° C. The mixture was stirred under 65° C. for 24 hours. TLC and HPLC showed that the reaction was completed. The solution was concentrated and purified by silica gel (MeOH/CH2Cl2=1:9) to get 8-IX (380 mg) in a 57% yield.

To a solution of 8-IX (210 mg) in CH2Cl2 (5 ml) was added TMSBr (312 mg) at 10-15° C. for 1 hour. The mixture was stirred at 25° C. for 15 hours. The solution was concentrated to remove TMSBr and solvent under vacuum at 40° C., then, CH2Cl2 was added to dissolve the residue. Then TMSBr and solvent were further removed under vacuum and CH2Cl2 was added for four times repeatedly. The solution was concentrated to get hydrobromide salt of compound 8 (190 mg).

CI-MS (M++1): 566.9

To do a job well is one thing, but to consistently deliver a product that is nearly flawless is quite a different challenge. For its new molecule burixafor, the Taiwanese drug discovery firm TaiGen Biotechnology instructed its contract manufacturing partners to achieve 99.8% purity in the production of the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API).

Discovered in TaiGen’s labs in 2006, burixafor is in Phase II clinical trials in both the U.S. and China for use in stem cell transplants and cancer chemotherapy. Avecia, a unit of Japan’s Nitto Denko, manufactures the drug substance in the U.S., where burixafor was tested for the first time on human patients. When TaiGen later initiated clinical trials in China, it chose the Taiwanese firm ScinoPharm to produce the drug at its plant in Changshu, near Shanghai. Under Chinese law, only drugs made domestically can be tested in China.

NITTO DENKO Avecia Inc.

It is rare for a drug discovery firm to select two companies to scale up the production of a new molecule. TaiGen went one step further by paying both contract manufacturers to reach an extremely high level of purity.

“We are trying to avoid any unwanted side effects during the trials,” says C. Richard King, TaiGen’s senior vice president of research. Drug regulators in the U.S. and China “need very tight specifications these days for new drugs,” he adds.

TaiGen registered burixafor with the U.S. Food & Drug Administration in 2007. When it contracted Girindus America (bought by Avecia in 2013) to manufacture it that year, TaiGen specified purification by column chromatography, a cumbersome and relatively expensive procedure when carried out on a large scale. “Our process development efforts were racing against the clinical trials launch schedule,” King recalls. Column chromatography, he points out, is a “tedious approach, but it works.”

By the time ScinoPharm was hired last year, TaiGen’s process development team had come up with a simpler and more elegant process. But its purity demands hadn’t changed.

“Usually, clients are satisfied with a purity level of 98% to 99%,” says Koksuan Tang, head of operations at ScinoPharm’s Changshu plant. “To go from 99% to 99.8% is very different.” The manufacturing of burixafor, he adds, involves five chemical steps and two purification steps. Upstream of the API, ScinoPharm also produces burixafor’s starting material.

Purity level aside, burixafor is not a particularly difficult compound to make, Tang says. Nonetheless, the process supplied by TaiGen had to be adjusted for larger-scale production. “If you heat up 10 g in the lab, it takes two minutes, but in a plant, it could take as long as two hours,” he says.

Although, while hydrogen chloride gas can be controlled effectively when making minute quantities of a compound in the lab, it’s another challenge to handle large volumes of the toxic substance at the plant level. To safely execute one reaction step, ScinoPharm dissolved HCl in a special solvent that does not affect the purity profile of burixafor.

TaiGen selected ScinoPharm as its China contractor after a careful process that involved two visits to Changshu by TaiGen’s senior managers, Tang recalls. ScinoPharm’s track record of meeting regulatory requirements in different countries, including China, was a plus, Tang believes. Its ability to produce both for clinical trials and in larger quantities after commercial launch was also decisive.

Operational since 2012, ScinoPharm’s Changshu site can deliver products under Good Manufacturing Practices in quantities ranging from grams to kilograms. It employs 220 people.

ScinoPharm (Changshu) Pharmaceuticals, Ltd.

“Moving from the single-kilogram quantities we make now to hundreds of kilograms will require some adjustment to the process, but we believe we can deliver,” says Tang’s colleague Sing Ping Lee, senior director of product technical support in Changshu. One thing to keep in mind, he notes, is that Chinese regulatory standards for drug production are actually more restrictive than those in the U.S. or Europe, going so far as specifying what equipment manufacturers need to use.

Other than complying with Chinese regulators, one reason TaiGen needed to carefully select its China contractor is that the two companies could well be long-term partners, since TaiGen believes it has the ability to market the drug on its own in China, Taiwan, and Southeast Asia. In the event of approvals elsewhere, TaiGen plans to license the compound to a large drug company, which may or may not stick with ScinoPharm or Avecia.

Relatively unknown outside Taiwan, TaiGen was formed in 2001 by Ming-Chu Hsu, the founder of the Division of Biotechnology & Pharmaceutical Research at Taiwan’s National Health Research Institutes. The holder of a Ph.D. in biochemistry from the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, she headed oncology and virology research at Roche for more than 10 years before returning to Taiwan in 1998.

Ming-Chu Hsu, Chairman & CEO, TaiGen Biotechnology, Taiwan

TaiGen employs about 80 people, three-quarters of whom are in R&D. The company develops its own drugs in-house and also in-licenses molecules that are in early stages of development. The company licenses out the molecules for the European Union and U.S. markets but seeks to retain Asian marketing rights. Burixafor was discovered in TaiGen’s own labs in Taipei. To come up with it, researchers used a high-throughput screening approach that involved 130,000 compounds, including the design and synthesis of 1,500 new compounds. “It went back and forth between chemistry and biology many times,” recalls King, TaiGen’s research head.

A so-called CXCR4 chemokine receptor antagonist, burixafor mobilizes hematopoietic stem cells and endothelial progenitor cells in human bone marrow and channels them into the peripheral blood within three hours of ingestion, according to results of Phase I and Phase II trials.

In the U.S., burixafor is undergoing clinical trials for use during stem cell transplantation in patients with multiple myeloma, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, or Hodgkin’s disease. In China, TaiGen is testing it as a chemotherapy sensitizer in relapsed or refractory adult acute myeloid leukemia.

Owing to its activity on CXCR4 chemokine receptors, the drug could also fight age-related macular degeneration and diabetic retinopathy diseases, as well as find use in tissue repair, King says. For clinical trials in the U.S., TaiGen has partnered with Michael W. Schuster, a medical doctor who conducts research at Stony Brook University Hospital in New York.

Dr. Michael Schuster is Gift of Life’s Medical Director, as well as the Director of the Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Program and Hematologic Malignancy Program of Stony Brook University Hospital in New York

Typical structure of a chemokine receptor

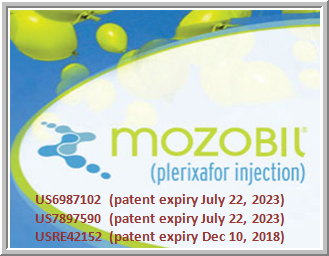

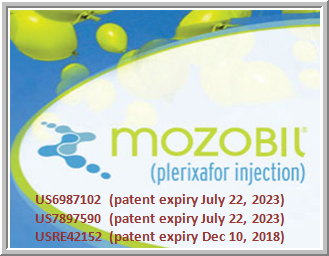

TaiGen sees particular potential for burixafor in stem cell applications. For example, patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation often must take a granulocyte colony-stimulating factor plus a Sanofi drug called Mozobil to stimulate stem cell production. TaiGen says burixafor could accomplish this goal on its own in multiple myeloma patients. It cites one consulting firm forecast that puts eventual sales at more than $1 billion per year.

Sanofi drug called Mozobil to stimulate stem cell production

With that kind of potential, the company is counting on significant interest among licensors, any one of which might want to engage its own contract producer of burixafor. If that happens, a third manufacturer will have to learn to reach 99.8% purity.

TaiGen Biotechnology Co., Ltd.

7F,138 Shin Ming Rd. Neihu Dist., Taipei, Taiwan 114 R.O.C

Tel: 886-2-81777072 | 886-2-27901861

Fax: 886-2-27963606

Taipei Railway Station front

Taipei Songshan Airport

Scinopharm

ScinoPharm (Changshu) Pharmaceuticals, Ltd.

ScinoPharm (Changshu) Pharmaceuticals, Ltd.

ScinoPharm is currently expanding its manufacturing and process development capabilities by adding significant production and technical capacity in Mainland China at its new Changshu site.

ScinoPharm Changshu is located in the Changshu Economic Development Zone (CEDZ), near Suzhou City, Jingsu Province, China on a 6.6-hectare site.

The facilities will include a R&D centre and production plants fully compliant with U.S. and international GMP standards. The Changshu plant, slated to be fully completed by 2012, will be used for the production of GMP grade pharmaceutical intermediates initially, and later be equipped to handle API production. China’s market for better quality APIs has grown considerably, and local formulation companies are encouraged to utilize APIs from companies having DMFs filed in advanced countries. ScinoPharm had closed its site in Kunshan and relocated the production and R&D groups to Changshu in the 4th quarter of 2011. These groups will continue to be expanded to meet growing demand for ScinoPharm products by both multinational and local formulation companies.

The small and medium-sized production units had been operational in the 4th quarter of 2011. The large production Bays plus a peptide purification unit, a high potency unit and a physical property processing facility will be operational by the end of 2012. Using advanced engineering designs, this site will also have the capability to process high potency, injectable grade products.

ScinoPharm Changshu will adopt the same quality systems as ScinoPharm Taiwan, and will therefore comply with ICH guidelines and FDA 21 CFR Parts 210 & 211.

TAIPEI

Old street in Taipei. 2013

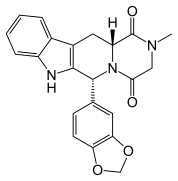

Tadalafil

Tadalafil

Aldrich Library of 13C and 1H FT NMR Spectra, 1992, 2, 915C

Aldrich Library of 13C and 1H FT NMR Spectra, 1992, 2, 915C

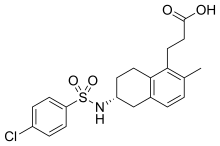

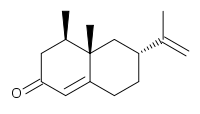

![3-[(6R)-6-[(4-chlorophenyl)sulfonylamino]-2-methyl-5,6,7,8-tetrahydronaphthalen-1-yl]propanoic acid NMR spectra analysis, Chemical CAS NO. 165538-40-9 NMR spectral analysis, 3-[(6R)-6-[(4-chlorophenyl)sulfonylamino]-2-methyl-5,6,7,8-tetrahydronaphthalen-1-yl]propanoic acid H-NMR spectrum](http://pic11.molbase.net/nmr/nmr_image/2014-11-09/001/775/1775661_1h.png)

![3-[(6R)-6-[(4-chlorophenyl)sulfonylamino]-2-methyl-5,6,7,8-tetrahydronaphthalen-1-yl]propanoic acid NMR spectra analysis, Chemical CAS NO. 165538-40-9 NMR spectral analysis, 3-[(6R)-6-[(4-chlorophenyl)sulfonylamino]-2-methyl-5,6,7,8-tetrahydronaphthalen-1-yl]propanoic acid C-NMR spectrum](http://pic11.molbase.net/nmr/nmr_image/2014-11-09/001/775/1775661_13c.png)

)/Images/CSIRlogo.gif)

)/Images/iictlogo.gif)

)/Images/iict70logo.gif)

DR AV RAMA RAO

DR AV RAMA RAO Professor J. R. Falck

Professor J. R. Falck Professor L. F. Tietze

Professor L. F. Tietze

CHINA

CHINA