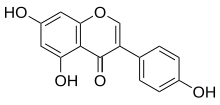

Genistein

5,7-Dihydroxy-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-4H-1-benzopyran-4-one; Baichanin A; Bonistein; 4’,5,7-Trihydroxyisoflavone; GeniVida; Genisteol; NSC 36586; Prunetol; Sophoricol;

| CAS Number: | 446-72-0 |

| BIO-300; G-2535; PTI-G-4660; SIPI-9764-I; PTIG-4660; SIPI-9764I | |

| Molecular form.: | C₁₅H₁₀O₅ |

| Appearance: | Light Tan to Light Yellow Solid |

| Melting Point: | >277°C (dec.) |

| Mol. Weight: | 270.24 |

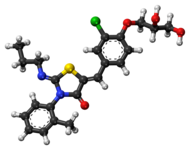

Genistein , an isoflavone found in many Fabaceae plants and important non-nutritional constituent of soybeans (Glycine max Merill), is a well-known plant metabolite from phenylpropanoid pathway, chiefly because of its presence in numerous phytoestrogenic dietary supplements. In fact, the compound also strives for higher medicinal status, undergoing dozens of clinical trials for various ailments, from osteoporosis to cancer

An EGFR/DNA topoisomerase II inhibitor potentially for the treatment of bladder cancer and prostate cancer.

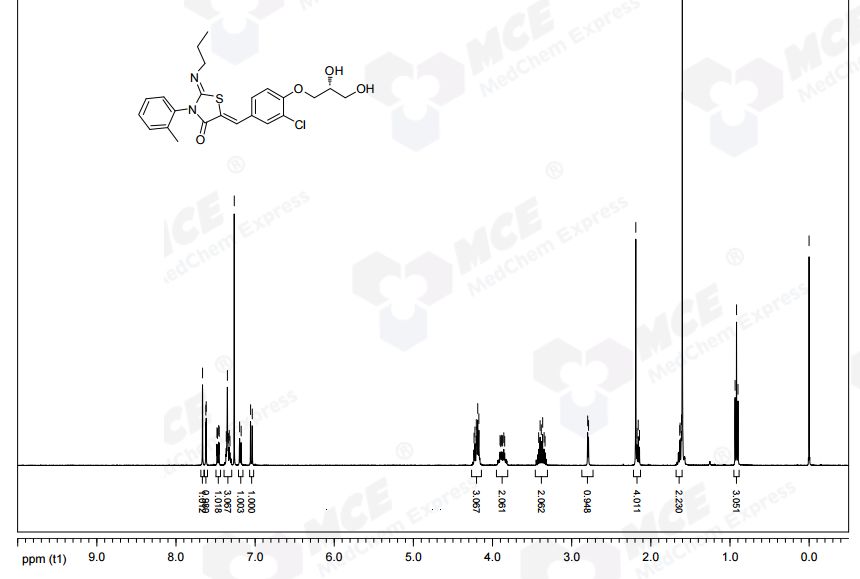

NMR

Genistein; CAS: 446-72-0

REF http://www.wangfei.ac.cn/nmrspectra/7/1/30

SEE https://www.google.com/patents/EP2373326A1?cl=en

Genistein is an angiogenesis inhibitor and a phytoestrogen and belongs to the category of isoflavones. Genistein was first isolated in 1899 from the dyer’s broom, Genista tinctoria; hence, the chemical name. The compound structure was established in 1926, when it was found to be identical with prunetol. It was chemically synthesized in 1928.[1]

Natural occurrences

Isoflavones such as genistein and daidzein are found in a number of plants including lupin, fava beans, soybeans, kudzu, andpsoralea being the primary food source,[2][3] also in the medicinal plants, Flemingia vestita[4] and F. macrophylla,[5][6] and coffee.[7] It can also be found in Maackia amurensis cell cultures.[8]

Extraction and purification

Most of the isoflavones in plants are present in a glycosylated form. The unglycosylated aglycones can be obtained through various means such as treatment with the enzyme β-glucosidase, acid treatment of soybeans followed by solvent extraction, or by chemical synthesis.[9] Acid treatment is a harsh method as concentrated inorganic acids are used. Both enzyme treatment and chemical synthesis are costly. A more economical process consisting of fermentation for in situ production of β-glucosidase to isolate genistein has been recently investigated.[10]

Biological effects

Besides functioning as antioxidant and anthelmintic, many isoflavones have been shown to interact with animal and human estrogen receptors, causing effects in the body similar to those caused by the hormone estrogen. Isoflavones also produce non-hormonal effects.

Molecular function

Genistein influences multiple biochemical functions in living cells:

- full agonist of ERβ (EC50 = 7.62 nM) and, to a much lesser extent (~20-fold), full agonist[11] or partial agonist of ERα[12]

- agonist of GPER (GPR30)[13]

- activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs)

- inhibition of several tyrosine kinases

- inhibition of topoisomerase

- inhibition of AAAD

- direct antioxidation with some proxidative features

- activation of Nrf2 antioxidative response

- stimulation of autophagy[14][15][16]

- inhibition of the mammalian hexose transporter GLUT1

- contraction of several types of smooth muscles

- modulation of CFTR channel, potentiating its opening at low concentration and inhibiting it a higher doses.

- inhibition of cytosine methylation

- inhibition of DNA methyltransferase[17]

- inhibition of the glycine receptor

Activation of PPARs

Isoflavones genistein and daidzein bind to and transactivate all three PPAR isoforms, α, δ, and γ.[18] For example, membrane-bound PPARγ-binding assay showed that genistein can directly interact with the PPARγ ligand binding domain and has a measurable Ki of 5.7 mM.[19] Gene reporter assays showed that genistein at concentrations between 1 and 100 uM activated PPARs in a dose dependent way in KS483 mesenchymal progenitor cells, breast cancer MCF-7 cells, T47D cells and MDA-MD-231 cells, murine macrophage-like RAW 264.7 cells, endothelial cells and in Hela cells. Several studies have shown that both ERs and PPARs influenced each other and therefore induce differential effects in a dose-dependent way. The final biological effects of genistein are determined by the balance among these pleiotrophic actions.[18][20][21]

Tyrosine kinase inhibitor

The main known activity of genistein is tyrosine kinase inhibitor, mostly of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). Tyrosine kinases are less widespread than their ser/thr counterparts but implicated in almost all cell growth and proliferation signal cascades.

Redox-active — not only antioxidant

Genistein may act as direct antioxidant, similar to many other isoflavones, and thus may alleviate damaging effects of free radicals in tissues.[22][23]

The same molecule of genistein, similar to many other isoflavones, by generation of free radicals poison topoisomerase II, an enzyme important for maintaining DNA stability.[24][25][26]

Human cells turn on beneficial, detoxyfying Nrf2 factor in response to genistein insult. This pathway may be responsible for observed health maintaining properities of small doses of genistein.[27]

Anthelmintic

The root-tuber peel extract of the leguminous plant Felmingia vestita is the traditional anthelmitic of the Khasi tribes of India. While investigating its anthelmintic activity, genistein was found to be the major isoflavone responsible for the deworming property.[4][28] Genistein was subsequently demonstrated to be highly effective against intestinal parasitessuch as the poultry cestode Raillietina echinobothrida,[28] the pork trematode Fasciolopsis buski,[29] and the sheep liver fluke Fasciola hepatica.[30] It exerts its anthelmintic activity by inhibiting the enzymes of glycolysis and glycogenolysis,[31][32] and disturbing the Ca2+ homeostasis and NO activity in the parasites.[33][34] It has also been investigated inhuman tapeworms such as Echinococcus multilocularis and E. granulosus metacestodes that genistein and its derivatives, Rm6423 and Rm6426, are potent cestocides.[35]

Atherosclerosis

Genistein protects against pro-inflammatory factor-induced vascular endothelial barrier dysfunction and inhibits leukocyte–endothelium interaction, thereby modulating vascular inflammation, a major event in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis.[36]

Cancer links

Genistein and other isoflavones have been identified as angiogenesis inhibitors, and found to inhibit the uncontrolled cell growth of cancer, most likely by inhibiting the activity of substances in the body that regulate cell division and cell survival (growth factors). Various studies have found that moderate doses of genistein have inhibitory effects on cancersof the prostate,[37][38] cervix,[39] brain,[40] breast[37][41][42] and colon.[16] It has also been shown that genistein makes some cells more sensitive to radio-therapy.;[43] although, timing of phytoestrogen use is also important. [43]

Genistein’s chief method of activity is as a tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Tyrosine kinases are less widespread than their ser/thr counterparts but implicated in almost all cell growth and proliferation signal cascades. Inhibition of DNA topoisomerase II also plays an important role in the cytotoxic activity of genistein.[25][44] Genistein has been used to selectively target pre B-cells via conjugation with an anti-CD19 antibody.[45]

Studies on rodents have found genistein to be useful in the treatment of leukemia, and that it can be used in combination with certain other antileukemic drugs to improve their efficacy.[46]

Estrogen receptor — more cancer links

Due to its structure similarity to 17β-estradiol (estrogen), genistein can compete with it and bind to estrogen receptors. However, genistein shows much higher affinity towardestrogen receptor β than toward estrogen receptor α.[47]

Data from in vitro and in vivo research confirms that genistein can increase rate of growth of some ER expressing breast cancers. Genistein was found to increase the rate of proliferation of estrogen-dependent breast cancer when not cotreated with an estrogen antagonist.[48][49][50] It was also found to decrease efficiency of tamoxifen and letrozole – drugs commonly used in breast cancer therapy.[51][52] Genistein was found to inhibit immune response towards cancer cells allowing their survival.[53]

Effects in males

Isoflavones can act like estrogen, stimulating development and maintenance of female characteristics, or they can block cells from using cousins of estrogen. In vitro studies have shown genistein to induce apoptosis of testicular cells at certain levels, thus raising concerns about effects it could have on male fertility;[54] however, a recent study found that isoflavones had “no observable effect on endocrine measurements, testicular volume or semen parameters over the study period.” in healthy males given isoflavone supplements daily over a 2-month period.[55]

Carcinogenic and toxic potential

Genistein was, among other flavonoids, found to be a strong topoisomerase inhibitor, similarly to some chemotherapeutic anticancer drugs ex. etoposide and doxorubicin.[24][56]In high doses it was found to be strongly toxic to normal cells.[57] This effect may be responsible for both anticarcinogenic and carcinogenic potential of the substance.[26][58] It was found to deteriorate DNA of cultured blood stem cells, what may lead to leukemia.[59] Genistein among other flavonoids is suspected to increase risk of infant leukemia when consumed during pregnancy.[60][61]

Sanfilippo syndrome treatment

Genistein decreases pathological accumulation of glycosaminoglycans in Sanfilippo syndrome. In vitro animal studies and clinical experiments suggest that the symptoms of the disease may be alleviated by adequate dose of genistein.[62] Genistein was found to also possess toxic properties toward brain cells.[57] Among many pathways stimulated by genistein, autophagy may explain the observed efficiency of the substance as autophagy is significantly impaired in the disease.[63][64]

Related compounds

Glycosides

Genistin is the 7-O-beta-D-glucoside of genistein.

Acetylated compounds

Wighteone is the 6-isopentenyl genistein (6-prenyl-5,7,4′-trihydroxyisoflavone)[citation needed]

Pharmaceutical derivatives

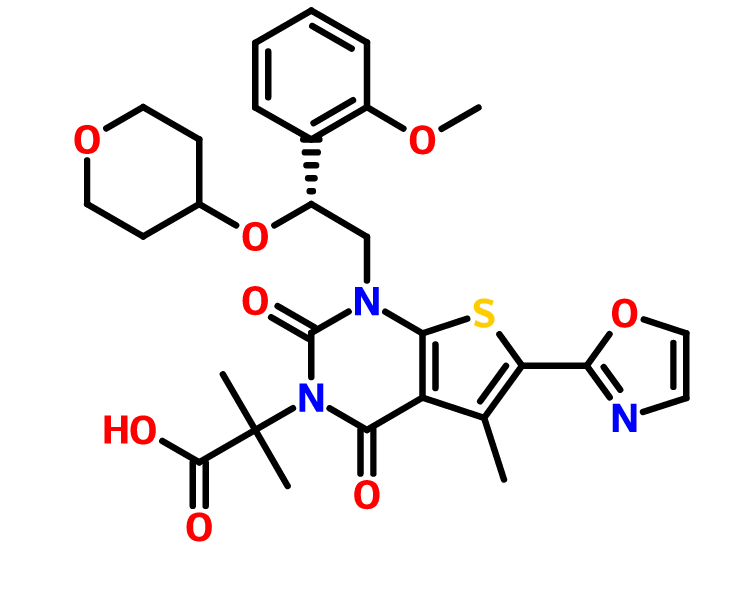

- KBU2046 under investigation for prostate cancer.[65][66]

- B43-genistein, an anti-CD19 antibody linked to genistein e.g. for leukemia.[67]

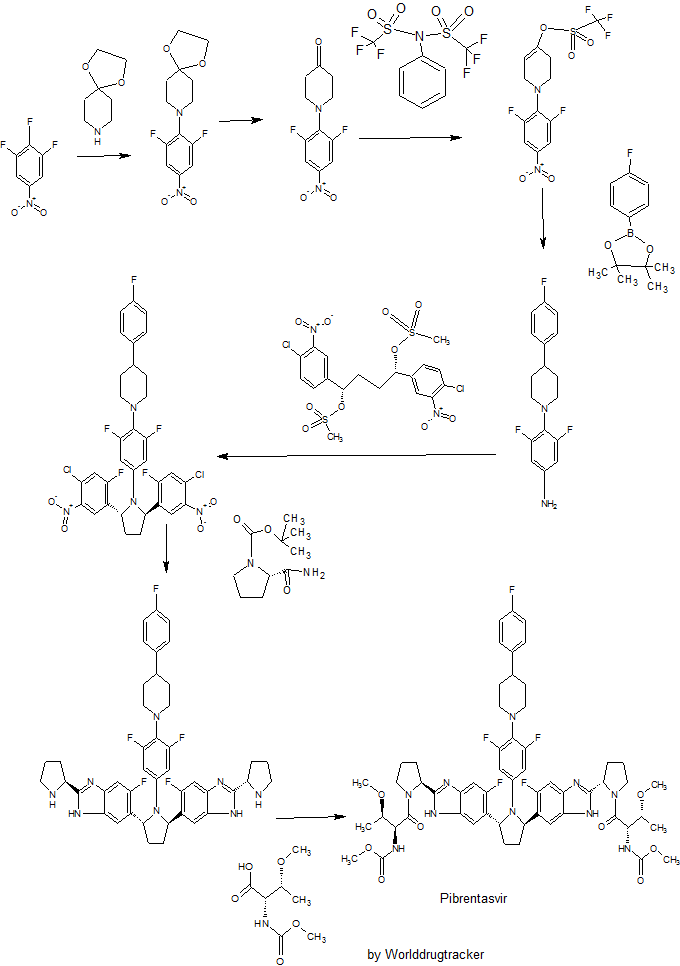

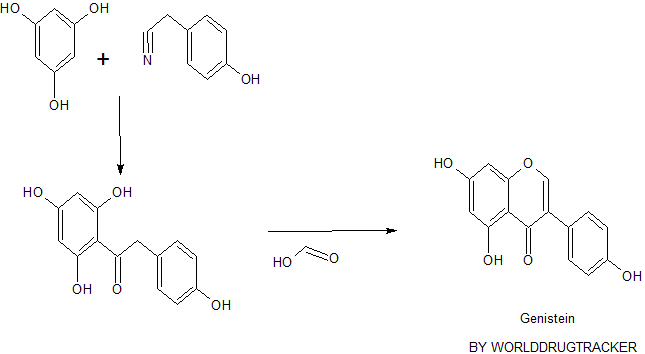

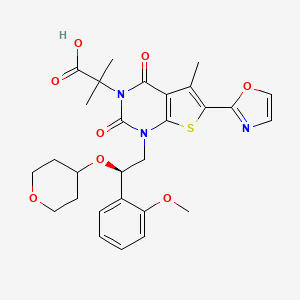

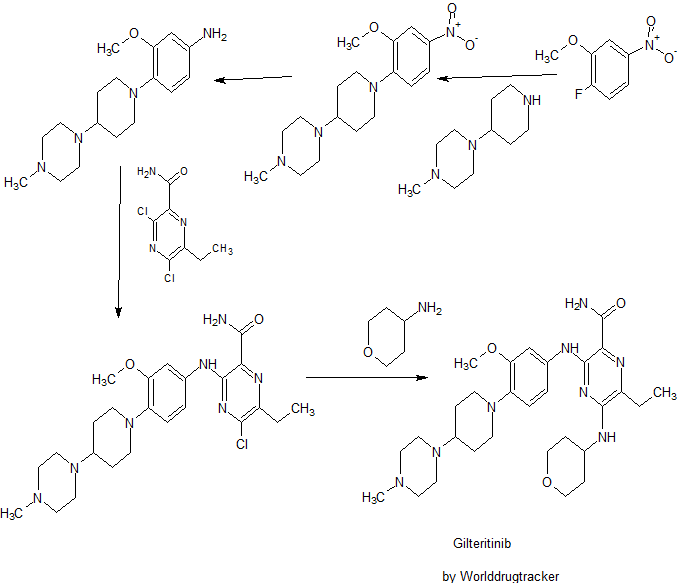

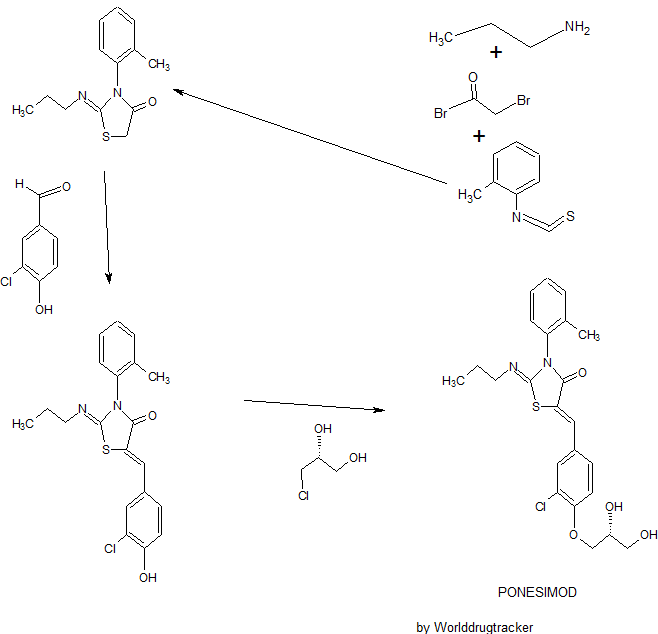

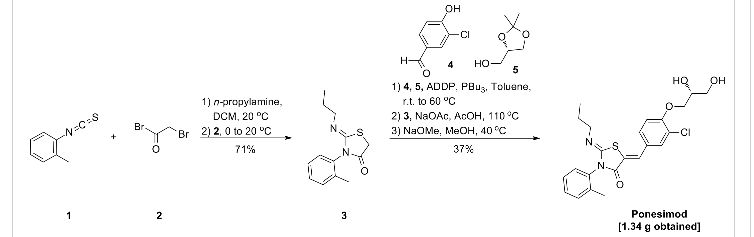

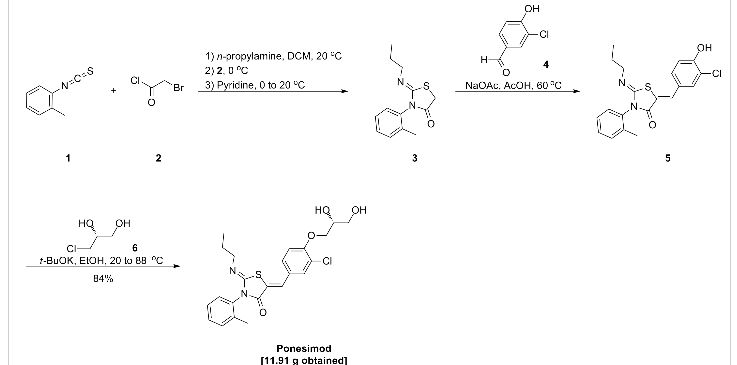

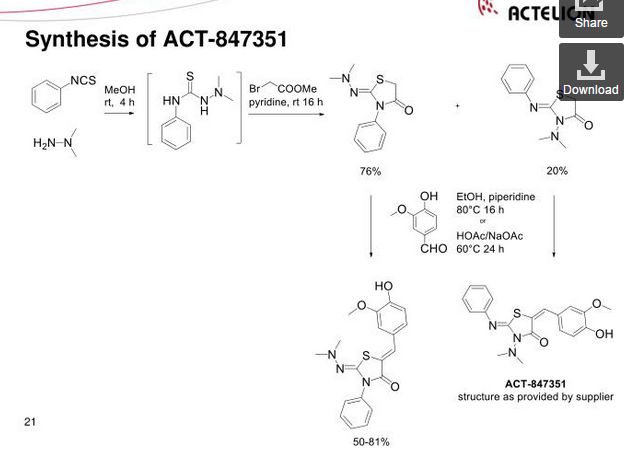

- Genistein has two known synthesis routes: deoxybenzoin route and chalcone route. Deoxybenzoin route uses friedel-craft reaction, and chalcone route uses aldol condensation as shown in figure 2. Developing synthesis of genistein allows the access to the affordable therapy as well as mass production of commercial genistein supplements. However, it would be recommended to consult with the health care provider and discuss the pros and cons before the use since the effects of genistein on human body are not fully understood yet as discussed above.

Figure 2. Synthesis of genistein via deoxybenzoin route or chalcone route. 10

https://chemprojects263sp11.wikispaces.com/genistein

Paper

Identification of Benzopyran-4-one Derivatives (Isoflavones) as Positive Modulators of GABAA Receptors

ChemMedChem (2011), 6, (8), 1340-1346

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cmdc.201100120/abstract

PATENT

By Achmatowicz, Osman et al

From Pol., 204473

References

- Walter, E. D. (1941). “Genistin (an Isoflavone Glucoside) and its Aglucone, Genistein, from Soybeans”. Journal of the American Chemical Society 63 (12): 3273–76.doi:10.1021/ja01857a013.

- Coward, Lori; Barnes, Neil C.; Setchell, Kenneth D. R.; Barnes, Stephen (1993). “Genistein, daidzein, and their β-glycoside conjugates: Antitumor isoflavones in soybean foods from American and Asian diets”. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 41 (11): 1961–7. doi:10.1021/jf00035a027.

- Jump up^ Kaufman, Peter B.; Duke, James A.; Brielmann, Harry; Boik, John; Hoyt, James E. (1997). “A Comparative Survey of Leguminous Plants as Sources of the Isoflavones, Genistein and Daidzein: Implications for Human Nutrition and Health”. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine 3 (1): 7–12. doi:10.1089/acm.1997.3.7.PMID 9395689.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Rao, H. S. P.; Reddy, K. S. (1991). “Isoflavones from Flemingia vestita“. Fitoterapia62 (5): 458.

- Jump up^ Rao, K.Nageswara; Srimannarayana, G. (1983). “Fleminone, a flavanone from the stems of Flemingia macrophylla“. Phytochemistry 22 (10): 2287–90. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(00)80163-6.

- Jump up^ Wang, Bor-Sen; Juang, Lih-Jeng; Yang, Jeng-Jer; Chen, Li-Ying; Tai, Huo-Mu; Huang, Ming-Hsing (2012). “Antioxidant and Antityrosinase Activity of Flemingia macrophylla andGlycine tomentella Roots”. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2012: 1–7. doi:10.1155/2012/431081. PMID 22997529.

- Jump up^ Alves, Rita C.; Almeida, Ivone M. C.; Casal, Susana; Oliveira, M. Beatriz P. P. (2010). “Isoflavones in Coffee: Influence of Species, Roast Degree, and Brewing Method”. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 58 (5): 3002–7. doi:10.1021/jf9039205.PMID 20131840.

- Jump up^ Fedoreyev, S.A; Pokushalova, T.V; Veselova, M.V; Glebko, L.I; Kulesh, N.I; Muzarok, T.I; Seletskaya, L.D; Bulgakov, V.P; Zhuravlev, Yu.N (2000). “Isoflavonoid production by callus cultures of Maackia amurensis”. Fitoterapia 71 (4): 365–72. doi:10.1016/S0367-326X(00)00129-5. PMID 10925005.

- Jump up^ Prakash, Om; Saini, Neena; Tanwar, Madan P.; Moriarty, Robert M. (1995). “Hypervalent iodine in organic synthesis: α-functionalization of carbonyl compounds”. Contemporary Organic Synthesis 2 (2): 121–31. doi:10.1039/CO9950200121.

- Jump up^ Patravale, VB; Pandit, NT (2011). “Design and optimization of a novel method for extraction of genistein”. Indian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 73 (2): 184–92.doi:10.4103/0250-474x.91583. PMC 3267303. PMID 22303062.

- Jump up^ Patisaul, Heather B.; Melby, Melissa; Whitten, Patricia L.; Young, Larry J. (2002). “Genistein Affects ERβ- But Not ERα-Dependent Gene Expression in the Hypothalamus”.Endocrinology 143 (6): 2189–2197. doi:10.1210/endo.143.6.8843. ISSN 0013-7227.

- Jump up^ Green, Sarah E (2015), In Vitro Comparison of Estrogenic Activities of Popular Women’s Health Botanicals

- Jump up^ Prossnitz, Eric R.; Barton, Matthias (2014). “Estrogen biology: New insights into GPER function and clinical opportunities”. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology 389 (1-2): 71–83.doi:10.1016/j.mce.2014.02.002. ISSN 0303-7207.

- Jump up^ Gossner, G; Choi, M; Tan, L; Fogoros, S; Griffith, K; Kuenker, M; Liu, J (2007). “Genistein-induced apoptosis and autophagocytosis in ovarian cancer cells”. Gynecologic Oncology 105 (1): 23–30. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.11.009. PMID 17234261.

- Jump up^ Singletary, K.; Milner, J. (2008). “Diet, Autophagy, and Cancer: A Review”. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention 17 (7): 1596–610. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2917. PMID 18628411.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Nakamura, Yoshitaka; Yogosawa, Shingo; Izutani, Yasuyuki; Watanabe, Hirotsuna; Otsuji, Eigo; Sakai, Tosiyuki (2009). “A combination of indol-3-carbinol and genistein synergistically induces apoptosis in human colon cancer HT-29 cells by inhibiting Akt phosphorylation and progression of autophagy”. Molecular Cancer 8: 100.doi:10.1186/1476-4598-8-100. PMC 2784428. PMID 19909554.

- Jump up^ Fang, Mingzhu; Chen, Dapeng; Yang, Chung S. (January 2007). “Dietary polyphenols may affect DNA methylation”. The Journal of Nutrition 137 (1 Suppl): 223S–228S.PMID 17182830.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Wang, Limei; Waltenberger, Birgit; Pferschy-Wenzig, Eva-Maria; Blunder, Martina; Liu, Xin; Malainer, Clemens; Blazevic, Tina; Schwaiger, Stefan; Rollinger, Judith M.; Heiss, Elke H.; Schuster, Daniela; Kopp, Brigitte; Bauer, Rudolf; Stuppner, Hermann; Dirsch, Verena M.; Atanasov, Atanas G. (2014). “Natural product agonists of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ): A review”. Biochemical Pharmacology 92: 73–89. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2014.07.018. PMC 4212005. PMID 25083916.

- Jump up^ Dang, Zhi-Chao; Audinot, Valérie; Papapoulos, Socrates E.; Boutin, Jean A.; Löwik, Clemens W. G. M. (2002). “Peroxisome Proliferator-activated Receptor γ (PPARγ) as a Molecular Target for the Soy Phytoestrogen Genistein”. Journal of Biological Chemistry 278(2): 962–7. doi:10.1074/jbc.M209483200. PMID 12421816.

- Jump up^ Dang, Zhi Chao; Lowik, Clemens (2005). “Dose-dependent effects of phytoestrogens on bone”. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism 16 (5): 207–13.doi:10.1016/j.tem.2005.05.001. PMID 15922618.

- Jump up^ Dang, Z. C. (2009). “Dose-dependent effects of soy phyto-oestrogen genistein on adipocytes: Mechanisms of action”. Obesity Reviews 10 (3): 342–9. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00554.x. PMID 19207876.

- Jump up^ Han, Rui-Min; Tian, Yu-Xi; Liu, Yin; Chen, Chang-Hui; Ai, Xi-Cheng; Zhang, Jian-Ping; Skibsted, Leif H. (2009). “Comparison of Flavonoids and Isoflavonoids as Antioxidants”.Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 57 (9): 3780–5. doi:10.1021/jf803850p.PMID 19296660.

- Jump up^ Borrás, Consuelo; Gambini, Juan; López-Grueso, Raúl; Pallardó, Federico V.; Viña, Jose (2010). “Direct antioxidant and protective effect of estradiol on isolated mitochondria”.Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 1802 (1): 205–11. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.09.007.PMID 19751829.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Bandele, Omari J.; Osheroff, Neil (2007). “Bioflavonoids as Poisons of Human Topoisomerase IIα and IIβ”. Biochemistry 46 (20): 6097–108. doi:10.1021/bi7000664.PMC 2893030. PMID 17458941.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Markovits, Judith; Linassier, Claude; Fossé, Philippe; Couprie, Jeanine; Pierre, Josiane; Jacquemin-Sablon, Alain; Saucier, Jean-Marie; Le Pecq, Jean-Bernard; Larsen, Annette K. (September 1989). “Inhibitory effects of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor genistein on mammalian DNA topoisomerase II”. Cancer Research 49 (18): 5111–7.PMID 2548712.

- ^ Jump up to:a b López-Lázaro, Miguel; Willmore, Elaine; Austin, Caroline A. (2007). “Cells Lacking DNA Topoisomerase IIβ are Resistant to Genistein”. Journal of Natural Products 70 (5): 763–7. doi:10.1021/np060609z. PMID 17411092.

- Jump up^ Mann, Giovanni E; Bonacasa, Barbara; Ishii, Tetsuro; Siow, Richard CM (2009). “Targeting the redox sensitive Nrf2–Keap1 defense pathway in cardiovascular disease: Protection afforded by dietary isoflavones”. Current Opinion in Pharmacology 9 (2): 139–45. doi:10.1016/j.coph.2008.12.012. PMID 19157984.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Tandon, V.; Pal, P.; Roy, B.; Rao, H. S. P.; Reddy, K. S. (1997). “In vitro anthelmintic activity of root-tuber extract of Flemingia vestita, an indigenous plant in Shillong, India”. Parasitology Research 83 (5): 492–8. doi:10.1007/s004360050286.PMID 9197399.

- Jump up^ Kar, Pradip K; Tandon, Veena; Saha, Nirmalendu (2002). “Anthelmintic efficacy ofFlemingia vestita: Genistein-induced effect on the activity of nitric oxide synthase and nitric oxide in the trematode parasite, Fasciolopsis buski“. Parasitology International 51 (3): 249–57. doi:10.1016/S1383-5769(02)00032-6. PMID 12243779.

- Jump up^ Toner, E.; Brennan, G. P.; Wells, K.; McGeown, J. G.; Fairweather, I. (2008). “Physiological and morphological effects of genistein against the liver fluke, Fasciola hepatica“. Parasitology 135 (10): 1189–203. doi:10.1017/S0031182008004630.PMID 18771609.

- Jump up^ Tandon, Veena; Das, Bidyadhar; Saha, Nirmalendu (2003). “Anthelmintic efficacy ofFlemingia vestita (Fabaceae): Effect of genistein on glycogen metabolism in the cestode,Raillietina echinobothrida“. Parasitology International 52 (2): 179–86. doi:10.1016/S1383-5769(03)00006-0. PMID 12798931.

- Jump up^ Das, B.; Tandon, V.; Saha, N. (2004). “Anthelmintic efficacy of Flemingia vestita(Fabaceae): Alteration in the activities of some glycolytic enzymes in the cestode,Raillietina echinobothrida“. Parasitology Research 93 (4): 253–61. doi:10.1007/s00436-004-1122-8. PMID 15138892.

- Jump up^ Das, Bidyadhar; Tandon, Veena; Saha, Nirmalendu (2006). “Effect of isoflavone from Flemingia vestita (Fabaceae) on the Ca2+ homeostasis in Raillietina echinobothrida, the cestode of domestic fowl”. Parasitology International 55 (1): 17–21.doi:10.1016/j.parint.2005.08.002. PMID 16198617.

- Jump up^ Das, Bidyadhar; Tandon, Veena; Lyndem, Larisha M.; Gray, Alexander I.; Ferro, Valerie A. (2009). “Phytochemicals from Flemingia vestita (Fabaceae) and Stephania glabra(Menispermeaceae) alter cGMP concentration in the cestode Raillietina echinobothrida“.Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part C: Toxicology & Pharmacology 149 (3): 397–403. doi:10.1016/j.cbpc.2008.09.012. PMID 18854226.

- Jump up^ Naguleswaran, Arunasalam; Spicher, Martin; Vonlaufen, Nathalie; Ortega-Mora, Luis M.; Torgerson, Paul; Gottstein, Bruno; Hemphill, Andrew (2006). “In Vitro Metacestodicidal Activities of Genistein and Other Isoflavones against Echinococcus multilocularis andEchinococcus granulosus“. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 50 (11): 3770–8.doi:10.1128/AAC.00578-06. PMC 1635224. PMID 16954323.

- Jump up^ Si, Hongwei; Liu, Dongmin; Si, Hongwei; Liu, Dongmin (2007). “Phytochemical Genistein in the Regulation of Vascular Function: New Insights”. Current Medicinal Chemistry 14(24): 2581–9. doi:10.2174/092986707782023325. PMID 17979711.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Morito, Keiko; Hirose, Toshiharu; Kinjo, Junei; Hirakawa, Tomoki; Okawa, Masafumi; Nohara, Toshihiro; Ogawa, Sumito; Inoue, Satoshi; Muramatsu, Masami; Masamune, Yukito (2001). “Interaction of Phytoestrogens with Estrogen Receptors α and β”. Biological & Pharmaceutical Bulletin 24 (4): 351–6. doi:10.1248/bpb.24.351. PMID 11305594.

- Jump up^ Hwang, Ye Won; Kim, Soo Young; Jee, Sun Ha; Kim, Youn Nam; Nam, Chung Mo (2009). “Soy Food Consumption and Risk of Prostate Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies”. Nutrition and Cancer 61 (5): 598–606.doi:10.1080/01635580902825639. PMID 19838933.

- Jump up^ Kim, Su-Hyeon; Kim, Su-Hyeong; Kim, Yong-Beom; Jeon, Yong-Tark; Lee, Sang-Chul; Song, Yong-Sang (2009). “Genistein Inhibits Cell Growth by Modulating Various Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases and AKT in Cervical Cancer Cells”. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1171: 495–500. Bibcode:2009NYASA1171..495K.doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04899.x. PMID 19723095.

- Jump up^ Das, Arabinda; Banik, Naren L.; Ray, Swapan K. (2009). “Flavonoids activated caspases for apoptosis in human glioblastoma T98G and U87MG cells but not in human normal astrocytes”. Cancer 116 (1): 164–76. doi:10.1002/cncr.24699. PMC 3159962.PMID 19894226.

- Jump up^ Sakamoto, Takako; Horiguchi, Hyogo; Oguma, Etsuko; Kayama, Fujio (2010). “Effects of diverse dietary phytoestrogens on cell growth, cell cycle and apoptosis in estrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer cells”. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 21 (9): 856–64. doi:10.1016/j.jnutbio.2009.06.010. PMID 19800779.

- Jump up^ de Lemos, Mário L (2001). “Effects of Soy Phytoestrogens Genistein and Daidzein on Breast Cancer Growth”. The Annals of Pharmacotherapy 35 (9): 1118–21.doi:10.1345/aph.10257. PMID 11573864.

- ^ Jump up to:a b de Assis, Sonia; Hilakivi-Clarke, Leena (2006). “Timing of Dietary Estrogenic Exposures and Breast Cancer Risk”. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1089: 14–35. Bibcode:2006NYASA1089…14D. doi:10.1196/annals.1386.039.PMID 17261753.

- Jump up^ López-Lázaro, Miguel; Willmore, Elaine; Austin, Caroline A. (2007). “Cells Lacking DNA Topoisomerase IIβ are Resistant to Genistein”. Journal of Natural Products 70 (5): 763–7.doi:10.1021/np060609z. PMID 17411092.

- Jump up^ Safa, Malek; Foon, Kenneth A.; Oldham, Robert K. (2009). “Drug Immunoconjugates”. In Oldham, Robert K.; Dillman, Robert O. Principles of Cancer Biotherapy (5th ed.). pp. 451–62. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-2289-9_12. ISBN 978-90-481-2277-6.

- Jump up^ Raynal, Noël J. M.; Charbonneau, Michel; Momparler, Louise F.; Momparler, Richard L. (2008). “Synergistic Effect of 5-Aza-2′-Deoxycytidine and Genistein in Combination Against Leukemia”. Oncology Research Featuring Preclinical and Clinical Cancer Therapeutics 17(5): 223–30. doi:10.3727/096504008786111356. PMID 18980019.

- Jump up^ Kuiper, George G. J. M.; Lemmen, Josephine G.; Carlsson, Bo; Corton, J. Christopher; Safe, Stephen H.; van der Saag, Paul T.; van der Burg, Bart; Gustafsson, Jan-Åke (1998). “Interaction of Estrogenic Chemicals and Phytoestrogens with Estrogen Receptor β”.Endocrinology 139 (10): 4252–63. doi:10.1210/endo.139.10.6216. PMID 9751507.

- Jump up^ Ju, Young H.; Allred, Kimberly F.; Allred, Clinton D.; Helferich, William G. (2006). “Genistein stimulates growth of human breast cancer cells in a novel, postmenopausal animal model, with low plasma estradiol concentrations”. Carcinogenesis 27 (6): 1292–9.doi:10.1093/carcin/bgi370. PMID 16537557.

- Jump up^ Chen, Wen-Fang; Wong, Man-Sau (2004). “Genistein Enhances Insulin-Like Growth Factor Signaling Pathway in Human Breast Cancer (MCF-7) Cells”. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 89 (5): 2351–9. doi:10.1210/jc.2003-032065.PMID 15126563.

- Jump up^ Yang, Xiaohe; Yang, Shihe; McKimmey, Christine; Liu, Bolin; Edgerton, Susan M.; Bales, Wesley; Archer, Linda T.; Thor, Ann D. (2010). “Genistein induces enhanced growth promotion in ER-positive/erbB-2-overexpressing breast cancers by ER-erbB-2 cross talk and p27/kip1 downregulation”. Carcinogenesis 31 (4): 695–702. doi:10.1093/carcin/bgq007.PMID 20067990.

- Jump up^ Helferich, W. G.; Andrade, J. E.; Hoagland, M. S. (2008). “Phytoestrogens and breast cancer: A complex story”. Inflammopharmacology 16 (5): 219–26. doi:10.1007/s10787-008-8020-0. PMID 18815740.

- Jump up^ Tonetti, Debra A.; Zhang, Yiyun; Zhao, Huiping; Lim, Sok-Bee; Constantinou, Andreas I. (2007). “The Effect of the Phytoestrogens Genistein, Daidzein, and Equol on the Growth of Tamoxifen-Resistant T47D/PKCα”. Nutrition and Cancer 58 (2): 222–9.doi:10.1080/01635580701328545. PMID 17640169.

- Jump up^ Jiang, Xinguo; Patterson, Nicole M.; Ling, Yan; Xie, Jianwei; Helferich, William G.; Shapiro, David J. (2008). “Low Concentrations of the Soy Phytoestrogen Genistein Induce Proteinase Inhibitor 9 and Block Killing of Breast Cancer Cells by Immune Cells”.Endocrinology 149 (11): 5366–73. doi:10.1210/en.2008-0857. PMC 2584580.PMID 18669594.

- Jump up^ Kumi-Diaka, James; Rodriguez, Rosanna; Goudaze, Gould (1998). “Influence of genistein (4′,5,7-trihydroxyisoflavone) on the growth and proliferation of testicular cell lines”. Biology of the Cell 90 (4): 349–54. doi:10.1016/S0248-4900(98)80015-4.PMID 9800352.

- Jump up^ Mitchell, Julie H.; Cawood, Elizabeth; Kinniburgh, David; Provan, Anne; Collins, Andrew R.; Irvine, D. Stewart (2001). “Effect of a phytoestrogen food supplement on reproductive health in normal males”. Clinical Science 100 (6): 613–8. doi:10.1042/CS20000212.PMID 11352776.

- Jump up^ Lutz, Werner K.; Tiedge, Oliver; Lutz, Roman W.; Stopper, Helga (2005). “Different Types of Combination Effects for the Induction of Micronuclei in Mouse Lymphoma Cells by Binary Mixtures of the Genotoxic Agents MMS, MNU, and Genistein”. Toxicological Sciences 86 (2): 318–23. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfi200. PMID 15901918.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Jin, Ying; Wu, Heng; Cohen, Eric M.; Wei, Jianning; Jin, Hong; Prentice, Howard; Wu, Jang-Yen (2007). “Genistein and daidzein induce neurotoxicity at high concentrations in primary rat neuronal cultures”. Journal of Biomedical Science 14 (2): 275–84.doi:10.1007/s11373-006-9142-2. PMID 17245525.

- Jump up^ Schmidt, Friederike; Knobbe, Christiane; Frank, Brigitte; Wolburg, Hartwig; Weller, Michael (2008). “The topoisomerase II inhibitor, genistein, induces G2/M arrest and apoptosis in human malignant glioma cell lines”. Oncology Reports 19 (4): 1061–6.doi:10.3892/or.19.4.1061. PMID 18357397.

- Jump up^ van Waalwijk van Doorn-Khosrovani, Sahar Barjesteh; Janssen, Jannie; Maas, Lou M.; Godschalk, Roger W. L.; Nijhuis, Jan G.; van Schooten, Frederik J. (2007). “Dietary flavonoids induce MLL translocations in primary human CD34+ cells”. Carcinogenesis 28(8): 1703–9. doi:10.1093/carcin/bgm102. PMID 17468513.

- Jump up^ Spector, Logan G.; Xie, Yang; Robison, Leslie L.; Heerema, Nyla A.; Hilden, Joanne M.; Lange, Beverly; Felix, Carolyn A.; Davies, Stella M.; Slavin, Joanne; Potter, John D.; Blair, Cindy K.; Reaman, Gregory H.; Ross, Julie A. (2005). “Maternal Diet and Infant Leukemia: The DNA Topoisomerase II Inhibitor Hypothesis: A Report from the Children’s Oncology Group”. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention 14 (3): 651–5. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0602. PMID 15767345.

- Jump up^ Azarova, Anna M.; Lin, Ren-Kuo; Tsai, Yuan-Chin; Liu, Leroy F.; Lin, Chao-Po; Lyu, Yi Lisa (2010). “Genistein induces topoisomerase IIbeta- and proteasome-mediated DNA sequence rearrangements: Implications in infant leukemia”. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 399 (1): 66–71. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.07.043.PMC 3376163. PMID 20638367.

- Jump up^ Piotrowska, Ewa; Jakóbkiewicz-Banecka, Joanna; Barańska, Sylwia; Tylki-Szymańska, Anna; Czartoryska, Barbara; Węgrzyn, Alicja; Węgrzyn, Grzegorz (2006). “Genistein-mediated inhibition of glycosaminoglycan synthesis as a basis for gene expression-targeted isoflavone therapy for mucopolysaccharidoses”. European Journal of Human Genetics 14(7): 846–52. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201623. PMID 16670689.

- Jump up^ Ballabio, A. (2009). “Disease pathogenesis explained by basic science: Lysosomal storage diseases as autophagocytic disorders”. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 47 (Suppl 1): S34–8. doi:10.5414/cpp47034.PMID 20040309.

- Jump up^ Settembre, Carmine; Fraldi, Alessandro; Jahreiss, Luca; Spampanato, Carmine; Venturi, Consuelo; Medina, Diego; de Pablo, Raquel; Tacchetti, Carlo; Rubinsztein, David C.; Ballabio, Andrea (2007). “A block of autophagy in lysosomal storage disorders”. Human Molecular Genetics 17 (1): 119–29. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddm289. PMID 17913701.

- Jump up^ Xu, Li; Farmer, Rebecca; Huang, Xiaoke; Pavese, Janet; Voll, Eric; Irene, Ogden; Biddle, Margaret; Nibbs, Antoinette; Valsecchi, Matias; Scheidt, Karl; Bergan, Raymond (2010). “Abstract B58: Discovery of a novel drug KBU2046 that inhibits conversion of human prostate cancer to a metastatic phenotype”. Cancer Prevention Research 3 (12 Supplement): B58. doi:10.1158/1940-6207.PREV-10-B58.

- Jump up^ “New Drug Stops Spread of Prostate Cancer” (Press release). Northwestern University. April 3, 2012. Retrieved September 27, 2014.

- Jump up^ Chen, Chun-Lin; Levine, Alexandra; Rao, Asha; O’Neill, Karen; Messinger, Yoav; Myers, Dorothea E.; Goldman, Frederick; Hurvitz, Carole; Casper, James T.; Uckun, Fatih M. (1999). “Clinical Pharmacokinetics of the CD19 Receptor-Directed Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor B43-Genistein in Patients with B-Lineage Lymphoid Malignancies”. The Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 39 (12): 1248–55. doi:10.1177/00912709922012051. PMID 10586390.

External links

- Compound Summary at NCBI PubChem

- Fact Sheet at Zerobreastcancer

- Information at Phytochemicals

- Chemical Compound Review at Wikigenes

- Information at Chemicalbook

- Description at SpringerReference

- Description at NCI Drug Dictionary

Development and scale-up of the synthetic process for genistein preparation are described. The process was designed with consideration for environmental and economical aspects and optimized in a laboratory scale. In a scale up, on every step quantity of the environmentally unfriendly substrates or solvents was reduced without compromising the quality of the final product, and the waste load was significantly diminished. The optimal duration times of the individual stages were determined, and the number of operations was reduced, leading to lowering of energy consumption. Elaborated process secures good yield and quality expected for pharmaceutical substances.

Technical Process for Preparation of Genistein

|

|

|

|

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

5,7-Dihydroxy-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)chromen-4-one

|

|

| Other names

4′,5,7-Trihydroxyisoflavone

|

|

| Identifiers | |

| 446-72-0 |

|

| ChEBI | CHEBI:28088 |

| ChEMBL | ChEMBL44 |

| ChemSpider | 4444448 |

| DrugBank | DB01645 |

| 2826 | |

| Jmol 3D model | Interactive image |

| KEGG | C06563 |

| PubChem | 5280961 |

| UNII | DH2M523P0H |

| Properties | |

| C15H10O5 | |

| Molar mass | 270.24 g·mol−1 |

|

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

|

|

Akiyama, T., et al.: J. Biol. Chem., 262, 5592 (1987), O’Dell, T.J., et al.: Nature, 353, 588 (1991), Aharonovits, O., et al.: Biochim Biophys. Acta, 1112, 181 (1992), Platanias, L.C., et al.: J. Biol. Chem., 267, 24053 (1992), Yoshida, H., et al.: Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1137, 321 (1992), Uckun, F.M., et al.: Science, 267, 886 (1995), Merck Index 12th ed. 4395, Huang, R.Q.; Fang, M.J.; Dillon, G.H., Mol. Brain Res. 67: 177-183 (1999)

//////BIO-300, G-2535, PTI-G-4660, SIPI-9764-I, PTIG-4660, SIPI-9764I, Genistein, phase 2, national cancer institute

Oc1ccc(cc1)C\3=C\Oc2cc(O)cc(O)c2C/3=O

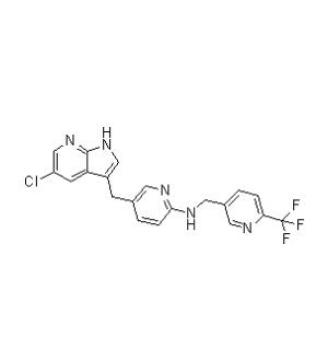

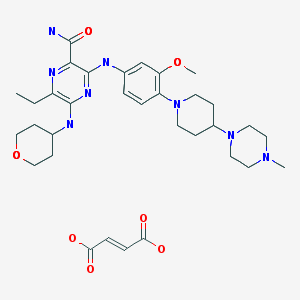

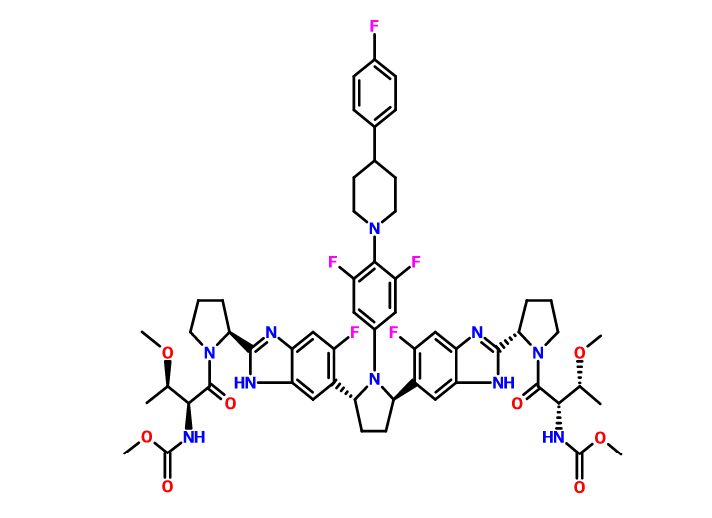

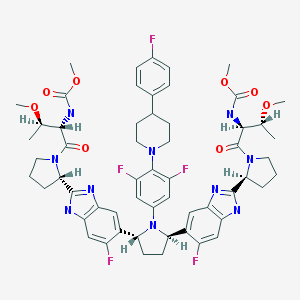

Pibrentasvir

Pibrentasvir