Vote

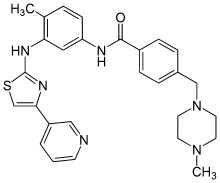

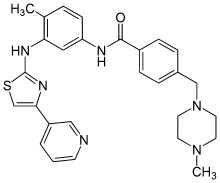

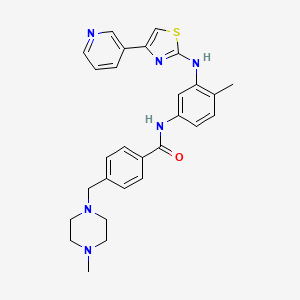

Masitinib

Masitinib; 790299-79-5; Masivet; AB1010; AB-1010;

TARGET:KIT (a stem cell factor, also called c-KIT) receptor as well as select other tyrosine kinases

COMMERCIAL:Under development by AB Science..

Ab Science

4-((4-Methylpiperazin-1-yl)methyl)-N-(4-methyl-3-((4-(pyridin-3-yl)-1,3-thiazol-2-yl)amino)phenyl)benzamide

AB 1010

UNII-M59NC4E26P

4-((4-Methylpiperazin-1-yl)methyl)-N-(4-methyl-3-((4-(pyridin-3-yl)-1,3-thiazol-2-yl)amino)phenyl)benzamide

Regulatory and Commercial Status

HIGHEST STATUS ACHIEVED (FOR ANY CONDITION):

Marketing Authorization Application for the treatment of pancreatic cancer has been filed with the European Medicines Agency (16 October 2012)

Marketing Authorization Application for the conditional approval in the treatment of pancreatic cancer has been accepted by the European Medicines Agency (30 October 2012)

Masitinib is a tyrosine-kinase inhibitor used in the treatment of mast cell tumors in animals, specifically dogs.[1][2] Since its introduction in November 2008 it has been distributed under the commercial name Masivet. It has been available in Europe since the second part of 2009. In the USA it is distributed under the name Kinavet and has been available for veterinaries since 2011.

Masitinib is being studied for several human conditions including cancers. It is used in Europe to fight orphan diseases.[3]

Mechanism of action

Masitinib inhibits the receptor tyrosine kinase c-Kit which is displayed by various types of tumour.[2] It also inhibits the platelet derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) and fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR).

……………………..

http://www.google.com/patents/US7423055

Compound Synthesis

General: All chemicals used were commercial reagent grade products. Dimethylformamide (DMF), methanol (MeOH) were of anhydrous commercial grade and were used without further purification. Dichloromethane and tetrahydrofuran (THF) were freshly distilled under a stream of argon before use. The progress of the reactions was monitored by thin layer chromatography using precoated silica gel 60F 254, Fluka TLC plates, which were visualized under UV light. Multiplicities in 1H NMR spectra are indicated as singlet (s), broad singlet (br s), doublet (d), triplet (t), quadruplet (q), and multiplet (m) and the NMR spectrum were realized on a 300 MHz Bruker spectrometer.

3-Bromoacetyl-pyridine, HBr Salt

Dibromine (17.2 g, 108 mmol) was added dropwise to a cold (0° C.) solution of 3-acetyl-pyridine (12 g, 99 mmol) in acetic acid containing 33% of HBr (165 mL) under vigourous stirring. The vigorously stirred mixture was warmed to 40° C. for 2 h and then to 75° C. After 2 h at 75° C., the mixture was cooled and diluted with ether (400 mL) to precipitate the product, which was recovered by filtration and washed with ether and acetone to give white crystals (100%). This material may be recrystallised from methanol and ether.

IR (neat): 3108, 2047, 2982, 2559, 1709, 1603, 1221, 1035, 798 cm−1—−1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ=5.09 (s, 2H, CH2Br); 7.88 (m, 1H, pyridyl-H); 8.63 (m, 1H, pyridyl-H); 8.96 (m, 1H, pyridyl-H); 9.29 (m, 1H, pyridyl-H).

Methyl-[4-(1-N-methyl-piperazino)-methyl]-benzoate

To methyl-4-formyl benzoate (4.92 g, 30 mmol) and N-methyl-piperazine (3.6 mL, 32 mmol) in acetonitrile (100 mL) was added dropwise 2.5 mL of trifluoroacetic acid. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 h. After slow addition of sodium cyanoborohydride (2 g, 32 mmol), the solution was left stirring overnight at room temperature. Water (10 mL) was then added to the mixture, which was further acidified with 1N HCl to pH=6-7. The acetonitrile was removed under reduced pressure and the residual aqueous solution was extracted with diethyl ether (4×30 mL). These extracts were discarded. The aqueous phase was then basified (pH>12) by addition of 2.5N aqueous sodium hydroxyde solution. The crude product was extracted with ethyl acetate (4×30 mL). The combined organic layers were dried over MgSO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure to afford a slightly yellow oil which became colorless after purification by Kugelrohr distillation (190° C.) in 68% yield.

IR(neat): 3322, 2944, 2802, 1721, 1612, 1457, 1281, 1122, 1012—1H NMR(CDCl3) δ=2.27 (s, 3H, NCH3); 2.44 (m, 8H, 2×NCH2CH2N); 3.53 (s, 2H, ArCH2N); 3.88 (s, 3H, OCH3); 7.40 (d, 2H, J=8.3 Hz, 2×ArH); 7.91 (d, 2H, J=8.3 Hz, 2×ArH)—3C NMR (CDCl3) δ=45.8 (NCH3); 51.8 (OCH3); 52.9 (2×CH2N); 54.9 (2×CH2N); 62.4 (ArCH2N); 128.7 (2×ArC); 129.3 (2×ArC); 143.7 (ArC); 166.7 (ArCO2CH3)-MS CI (m/z) (%) 249 (M+1, 100%).

2-Methyl-5-tert-butoxycarbonylamino-aniline

A solution of di-tert-butyldicarbonate (70 g, 320 mmol) in methanol (200 mL) was added over 2 h to a cold (−10° C.) solution of 2,4-diaminotoluene (30 g, 245 mmol) and triethylamine (30 mL) in methanol (15 mL). The reaction was followed by thin layer chromatography (hexane/ethyl acetate, 3:1) and stopped after 4 h by adding 50 mL of water. The mixture was concentrated in vacuo and the residue was dissolved in 500 mL of ethyl acetate. This organic phase was washed with water (1×150 mL) and brine (2×150 mL), dried over MgSO4, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The resulting light brown solid was washed with small amounts of diethyl ether to give off-white crystals of 2-methyl-5-tert-butoxycarbonylamino-aniline in 67% yield.

IR (neat): 3359; 3246; 2970; 1719; 1609; 1557; 1173; 1050 cm−1—1H NMR (CDCl3): δ=1.50 (s, 9H, tBu); 2.10 (s, 3H, ArCH3); 3.61 (br s, 2H, NH2); 6.36 (br s, 1H, NH); 6.51 (dd, 1H, J=7.9 Hz, 2.3 Hz, ArH); 6.92 (d, 1H, J=7.9 Hz, ArH); 6.95 (s, 1H, ArH)—13C NMR (CDCl3) δ=16.6 (ArCH3); 28.3 (C(CH3)3); 80.0 (C(CH3)3); 105.2 (ArC); 108.6 (ArC); 116.9 (ArC); 130.4 (ArC—CH3); 137.2 (ArC—NH); 145.0 (ArC—NH2); 152.8 (COOtBu) MS ESI (m/z) (%): 223 (M+1), 167 (55, 100%).

N-(2-methyl-5-tert-butoxycarbonylamino)phenyl-thiourea

Benzoyl chloride (5.64 g, 80 mmol) was added dropwise to a well-stirred solution of ammonium thiocyanate (3.54 g, 88 mmol) in acetone (50 mL). The mixture was refluxed for 15 min, then, the hydrobromide salt of 2-methyl-5-tert-butoxycarbonylamino-aniline (8.4 g, 80 mmol) was added slowly portionswise. After 1 h, the reaction mixture was poured into ice-water (350 mL) and the bright yellow precipitate was isolated by filtration. This crude solid was then refluxed for 45 min in 70 mL of 2.5 N sodium hydroxide solution. The mixture was cooled down and basified with ammonium hydroxide. The precipitate of crude thiourea was recovered by filtration and dissolved in 150 mL of ethyl acetate. The organic phase was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by column chromatography (hexane/ethyl acetate, 1:1) to afford 63% of N-(2-methyl-5-tert-butoxycarbonylamino)phenyl-thiourea as a white solid.

IR (neat): 3437, 3292, 3175, 2983, 1724, 1616, 1522, 1161, 1053 cm−1— 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ=1.46 (s, 9H, tBu); 2.10 (s, 3H, ArCH3); 3.60 (br s, 2H, NH2); 7.10 (d, 1H, J=8.29 Hz, ArH); 7.25 (d, 1H, J=2.23 Hz, ArH); 7.28 (d, 1H, J=2.63 Hz, ArH); 9.20 (s, 1H, ArNH); 9.31 (s, 1H, ArNH)—13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ=25.1 (ArCH3); 28.1 (C(CH3)3); 78.9 (C(CH3)3); 16.6 (ArC); 117.5 (ArC); 128.0 (ArC); 130.4 (ArC—CH3); 136.5 (ArC—NH); 137.9 (ArC—NH); 152.7 (COOtBu); 181.4 (C═S)—MS CI(m/z): 282 (M+1, 100%); 248 (33); 226 (55); 182 (99); 148 (133); 93 (188).

2-(2-methyl-5-tert-butoxycarbonylamino)phenyl-4-(3-pyridyl)-thiazole

A mixture of 3-bromoacetyl-pyridine, HBr salt (0.81 g, 2.85 mmol), N-(2-methyl-5-tert-butoxycarbonylamino)phenyl-thiourea (0.8 g, 2.85 mmol) and KHCO3 (˜0.4 g) in ethanol (40 mL) was heated at 75° C. for 20 h. The mixture was cooled, filtered (removal of KHCO3) and evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was dissolved in CHCl3 (40 mL) and washed with saturated aqueous sodium hydrogen carbonate solution and with water. The organic layer was dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated. Colum chromatographic purification of the residue (hexane/ethyl acetate, 1:1) gave the desired thiazole in 70% yield as an orange solid

IR(neat): 3380, 2985, 2942, 1748, 1447, 1374, 1239, 1047, 938—1H NMR (CDCl3) δ=1.53 (s, 9H, tBu); 2.28 (s, 3H, ArCH3); 6.65 (s, 1H, thiazole-H); 6.89 (s, 1H); 6.99 (dd, 1H, J=8.3 Hz, 2.3 Hz); 7.12 (d, 2H, J=8.3 Hz); 7.35 (dd, 1H, J=2.6 Hz, 4.9 Hz); 8.03 (s, 1H); 8.19 (dt, 1H, J=1.9 Hz, 7.9 Hz); 8.54 (br s, 1H, NH); 9.09 (s, 1H, NH)—13C NMR (CDCl3) δ=18.02 (ArCH3); 29.2 (C(CH3)3); 81.3 (C(CH3)3); 104.2 (thiazole-C); 111.6; 115.2; 123.9; 124.3; 131.4; 132.1; 134.4; 139.5; 148.2; 149.1; 149.3; 153.6; 167.3 (C═O)—MS Cl (m/z) (%): 383 (M+1, 100%); 339 (43); 327 (55); 309 (73); 283 (99); 71 (311).

2-(2-methyl-5-amino)phenyl-4-(3-pyridyl)-thiazole

2-(2-methyl-5-tert-butoxycarbonylamino)phenyl-4-(3-pyridyl)-thiazole (0.40 g, 1.2 mmol) was dissolved in 10 mL of 20% TFA/CH2Cl2. The solution was stirred at rool temperature for 2 h, then it was evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was dissolved in ethyl acetate. The organic layer was washed with aqueous 1N sodium hydroxide solution, dried over MgSO4, and concentrated to afford 2-(2-methyl-5-amino)phenyl-4-(3-pyridyl)-thiazole as a yellow-orange solid in 95% yield. This crude product was used directly in the next step.

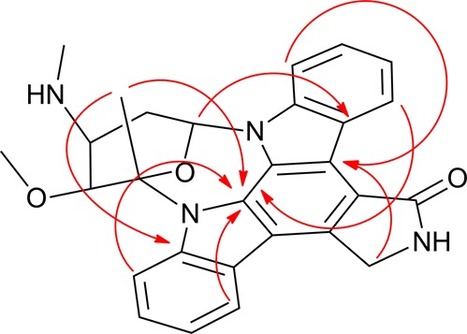

A 2M solution of trimethyl aluminium in toluene (2.75 mL) was added dropwise to a cold (0° C.) solution of 2-(2-methyl-5-amino)phenyl-4-(3-pyridyl)-thiazole (0.42 g, 1.5 mmol) in anhydrous dichloromethane (10 mL) under argon atmosphere. The mixture was warmed to room temperature and stirred at room temperature for 30 min. A solution of methyl-4-(1-N-methyl-piperazino)-methyl benzoate (0.45 g, 1.8 mmol) in anhydrous dichloromethane (1 mL) and added slowly, and the resulting mixture was heated at reflux for 5 h. The mixture was cooled to 0° C. and quenched by dropwise addition of a 4N aqueous sodium hydroxide solution (3 mL). The mixture was extracted with dichloromethane (3×20 mL). The combined organic layers were washed with brine (3×20 mL) and dried over anhydrous MgSO4. (2-(2-methyl-5-amino)phenyl-4-(3-pyridyl)-thiazole) is obtained in 72% after purification by column chromatography (dichloromethane/methanol, 3:1)

IR (neat): 3318, 2926, 1647, 1610, 1535, 1492, 1282, 1207, 1160, 1011, 843—

1H NMR (CDCl3) δ=2.31 (br s, 6H, ArCH3+NCH3); 2.50 (br s, 8H, 2×NCH2CH2N); 3.56 (s, 2H, ArCH2N); 6.89 (s, 1H, thiazoleH); 7.21-7.38 (m, 4H); 7.45 (m, 2H); 7.85 (d, 2H, J=8.3 Hz); 8.03 (s, 1H); 8.13 (s, 1H); 8.27 (s, 1H); 8.52 (br s, 1H); 9.09 (s, 1H, NH)—

13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 17.8 (ArCH3); 46.2 (NCH3); 53.3 (NCH2); 55.3 (NCH2); 62.8 (ArCH2N); 99.9 (thiazole-C); 112.5; 123.9; 125.2; 127.5; 129.6; 131.6; 133.7; 134.0; 137.6; 139.3; 142.9; 148.8; 149.1; 166.2 (C═O); 166.7 (thiazoleC-NH)—

MS CI (m/z) (%): 499 (M+H, 100%); 455 (43); 430 (68); 401 (97); 374 (124); 309 (189); 283 (215); 235 (263); 121 (377); 99 (399).

………………………

http://www.google.com/patents/WO2012136732A1?cl=en

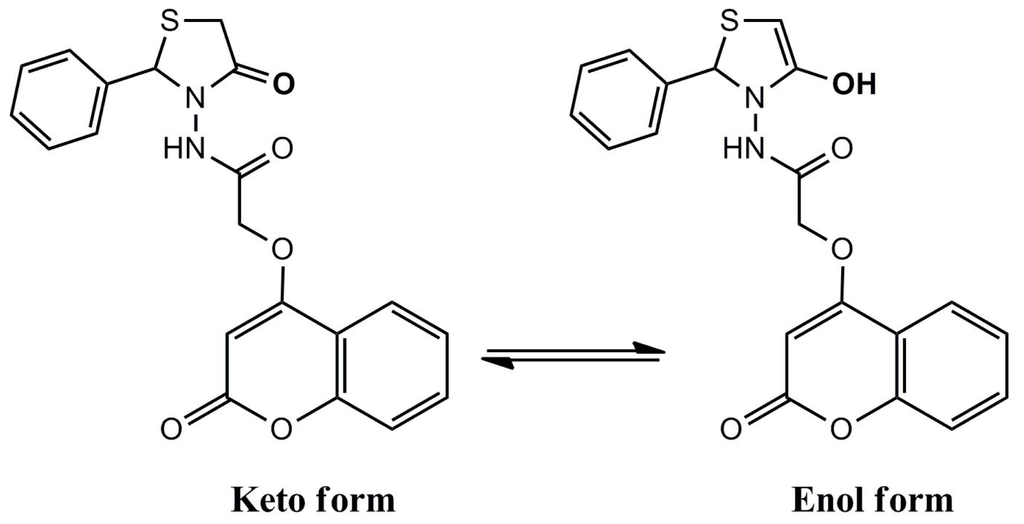

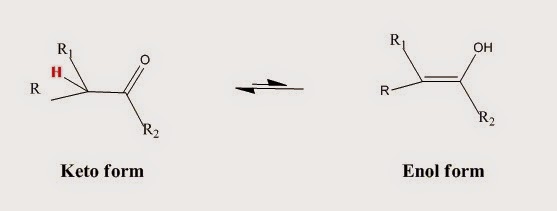

In a preferred embodiment of the above-depicted treatment, the active ingredient masitinib is administered in the form of masitinib mesilate; which is the orally bioavailable mesylate salt of masitinib – CAS 1048007-93-7 (MsOH); C28H30N6OS.CH3SO3H; MW 594.76:

http://www.google.com/patents/WO2004014903A1?cl=en

003 : 4-(4-Methyl-piperazin-l-ylmethyl)-N-[3-(4-pyridin-3-yl-thiazol-2-ylamino)- phenyl] -benzamide

4-(4-Methyl-piperazin-l-yl)-N-[4-methyl-3-(4-pyridin-3-yl-thiazol-2-ylmethyl)- phenyl] -benzamide

beige brown powder mp : 128-130°C

1H RMN (DMSO-d6) δ = 2.15 (s, 3H) ; 2.18 (s, 3H) ; 2.35-2.41 (m, 4H) ; 3.18-3.3.24 (m, 4H) ; 6.94 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H) ; 7.09 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, IH) ; 7.28-7.38 (m, 3H) ; 7.81 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H) ; 8.20-8.25 (m, IH) ; 8.40 (dd, J = 1.6 Hz, J = 4.7 , IH) ; 8.48 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, IH) ; 9.07 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, IH) ; 9.35 (s, IH) ; 9.84 (s, IH)

……………

http://www.google.com/patents/WO2008098949A2?cl=en

EXAMPLE 4 N- [4-Methyl-3 -(4-pyridin-3 -yl-thiazol-2-ylamino)-phenyl] -benzamide derivatives

Method A In a reactor and under low nitrogen pressure, add 4-Methyl-N3-(4-pyridin-3-yl-thiazol- 2-yl)-benzene-l,3-diamine (95 g, 336.45 mmol), dichloromethane (2 L). To this suspension cooled to temperature of 5°C was added dropwise 2M/n-hexane solution of trimethylaluminium (588 mL). The reaction mixture was brought progressively to 15°C, and maintained for 2 h under stirring. 4-(4-Methyl-piperazin-l-ylmethyl)-benzoic acid methyl ester (100 g, 402.71 mmol) in dichloromethane (200 mL) was added for 10 minutes. After 1 h stirring at room temperature, the reaction mixture was heated to reflux for 20 h and cooled to room temperature. This solution was transferred dropwise via a cannula to a reactor containing 2N NaOH (2.1 L) cooled to 5°C. After stirring for 3 h at room temperature, the precipitate was filtered through Celite. The solution was extracted with dichloromethane and the organic layer was washed with water and saturated sodium chloride solution, dried over MgSO4 and concentrated under vacuum. The brown solid obtained was recrystallized from /-Pr2O to give 130.7 g (78%) of a beige powder.

Method B Preparation of the acid chloride

To a mixture of 4-(4-Methyl-piperazin-l-ylmethyl)-benzoic acid dihydrochloride (1.0 eq), dichloromethane (7 vol) and triethylamine (2.15 eq), thionyl chloride (1.2 eq) was added at 18-28°C . The reaction mixture was stirred at 28-32°C for 1 hour. Coupling of acid chloride with amino thiazole To a chilled (0-50C) suspension of 4-Methyl-N3-(4-pyridin-3-yl-thiazol-2-yl)-benzene- 1,3-diamine (0.8 eq) and thiethylamine (2.2 eq) in dichloromethane (3 vol), the acid chloride solution (prepared above) was maintaining the temperature below 5°C. The reaction mixture was warmed to 25-300C and stirred at the same temperature for 1O h. Methanol (2 vol) and water (5 vol) were added to the reaction mixture and stirred. After separating the layers, methanol (2 vol), dihloromethane (5 vol) and sodium hydroxide solution (aqueous, 10%, till pH was 9.5-10.0) were added to the aqueous layer and stirred for 10 minutes. The layers were separated. The organic layer was a washed with water and saturated sodium chloride solution. The organic layer was concentrated and ethanol (2 vol) was added and stirred. The mixture was concentrated. Ethanol was added to the residue and stirred. The product was filtered and dried at 50-550C in a vaccum tray drier. Yield = 65-75%.

Method C

To a solution of 4-methyl-N3-(4-pyridin-3-yl-thiazol-2-yl)-benzene-l,3-diamine (1.0 eq) in DMF (20 vol) were added successively triethylamine (5 eq), 2-chloro-l- methylpyridinium iodide (2 eq) and 4-(4-methyl-piperazin-l-ylmethyl)-benzoic acid (2 eq). The reaction mixture was stirred for 7 h at room temperature. Then, the mixture was diluted in diethyl ether and washed with water and saturated aqueous NaHCO3, dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated. The crude product was purified by column chromatography using an elution of 100% EtOAc to give a yellow solid.

Yield = 51%.

1H NMR (CDCl3) : δ = 9.09 (IH, s, NH); 8.52 (IH, br s); 8.27 (IH, s); 8.13 (IH, s);

8.03 (IH, s); 7.85 (2H, d, J= 8.3Hz); 7.45 (2H, m); 7.21-7.38 (4H, m); 6.89 (IH, s);

3.56 (2H, s); 2.50 (8H, br s); 2.31 (6H, br s).

MS (CI) m/z = 499 (M+H)+.

An additional aspect of the present invention relates to a particular polymorph of the methanesulfonic acid salt of N-[4-Methyl-3-(4-pyridin-3-yl-thiazol-2-ylamino)-phenyl]- benzamide of formula (IX).

(VI)

Hereinafter is described the polymorph form of (IX) which has the most advantageous properties concerning processability, storage and formulation. For example, this form remains, dry at 80% relative humidity and thermodynamically stable at temperatures below 2000C.

The polymorph of this form is characterized by an X-ray diffraction pattern illustrated in FIG.I, comprising characteristic peaks approximately 7.269, 9.120, 11.038, 13.704, 14.481, 15.483, 15.870, 16.718, 17.087, 17.473, 18.224, 19.248, 19.441, 19.940, 20.441, 21.469, 21.750, 22.111, 23.319, 23.763, 24.120, 24.681, 25.754, 26.777, 28.975, 29.609, 30.073 degrees θ, and is also characterized by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) illustrated in FIG.II, which exhibit a single maximum value at approximately 237.49 ± 0.3 0C. X-ray diffraction pattern is measured using a Bruker AXS (D8 advance). Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) is measured using a Perking Elmer Precisely (Diamond DSC).

This polymorph form can be obtained by treatement of 4-(4-Methyl-piperazin-l- ylmethyl)-N-[4-methyl-3-(4-pyridin-3-yl-thiazol-2-ylamino)-phenyl]-benzamide with 1.0 to 1.2 equivalent of methanesulfonic acid, at a suitable temperature, preferably between 20-800C.

The reaction is performed in a suitable solvent especially polar solvent such as methanol or ethanol, or ketone such as acetone, or ether such as diethylether or dioxane, or a mixture therof. This invention is explained in example given below which is provided by way of illustration only and therefore should not be construed to limit the scope of the invention. Preparation of the above-mentioned polymorph form of 4-(4-Methyl-piperazin-l- ylmethyl)-N- [4-methyl-3 -(4-pyridin-3 -yl-thiazol-2-ylamino)-phenyl] -benzamide methanesulfonate .

4-(4-Methyl-piperazin- 1 -ylmethyl)-N- [4-methyl-3 -(4-pyridin-3 -yl-thiazol-2-ylamino) phenyl] -benzamide (1.0 eq) was dissolved in ethanol (4.5 vol) at 65-700C. Methanesulfonic acid (1.0 eq) was added slowly at the same temperature. The mixture was cooled to 25-300C and maintained for 6 h. The product was filtered and dried in a vacuum tray drier at 55-600C. Yield = 85-90%. Starting melting point Smp = 236°C.

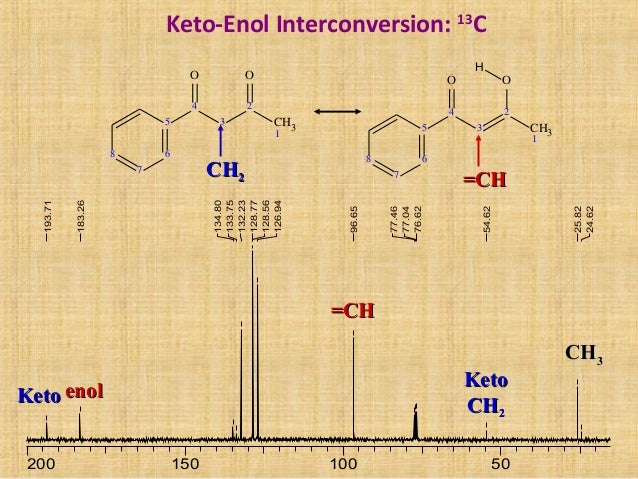

NMR PREDICT

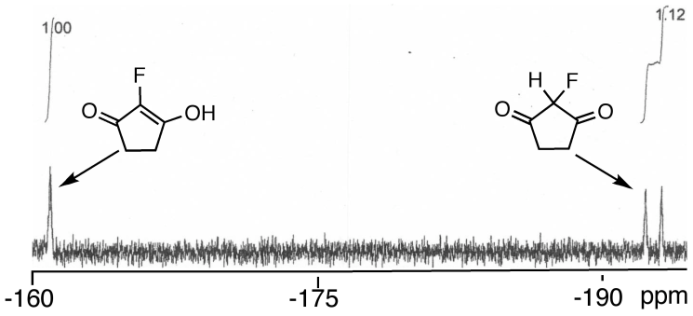

CAS NO. 1048007-93-7, methanesulfonic acid,4-[(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)methyl]-N-[4-methyl-3-[(4-pyridin-3-yl-1,3-thiazol-2-yl)amino]phenyl]benzamide H-NMR spectral analysis

![methanesulfonic acid,4-[(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)methyl]-N-[4-methyl-3-[(4-pyridin-3-yl-1,3-thiazol-2-yl)amino]phenyl]benzamide NMR spectra analysis, Chemical CAS NO. 1048007-93-7 NMR spectral analysis, methanesulfonic acid,4-[(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)methyl]-N-[4-methyl-3-[(4-pyridin-3-yl-1,3-thiazol-2-yl)amino]phenyl]benzamide H-NMR spectrum](http://pic11.molbase.net/nmr/nmr_image/2015-01-15/001/603/1603135_1h.png)

![methanesulfonic acid,4-[(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)methyl]-N-[4-methyl-3-[(4-pyridin-3-yl-1,3-thiazol-2-yl)amino]phenyl]benzamide NMR spectra analysis, Chemical CAS NO. 1048007-93-7 NMR spectral analysis, methanesulfonic acid,4-[(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)methyl]-N-[4-methyl-3-[(4-pyridin-3-yl-1,3-thiazol-2-yl)amino]phenyl]benzamide C-NMR spectrum](http://pic11.molbase.net/nmr/nmr_image/2015-01-15/001/603/1603135_13c.png)

CAS NO. 1048007-93-7, methanesulfonic acid,

4-[(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)methyl]-N-[4-methyl-3-[(4-pyridin-3-yl-1,3-thiazol-2-yl)amino]phenyl]benzamide C-NMR spectral analysisPREDICT

References

- Hahn, K.A.; Oglivie, G.; Rusk, T.; Devauchelle, P.; Leblanc, A.; Legendre, A.; Powers, B.; Leventhal, P.S.; Kinet, J.-P.; Palmerini, F.; Dubreuil, P.; Moussy, A.; Hermine, O. (2008). “Masitinib is Safe and Effective for the Treatment of Canine Mast Cell Tumors”. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 22 (6): 1301–1309. doi:10.1111/j.1939-1676.2008.0190.x. ISSN 0891-6640.

- Information about Masivet at the European pharmacy agency website

- Orphan designation for Masitinib at the European pharmacy agency website

| WO2004014903A1 |

Jul 31, 2003 |

Feb 19, 2004 |

Ab Science |

2-(3-aminoaryl)amino-4-aryl-thiazoles and their use as c-kit inhibitors |

| WO2008098949A2 |

Feb 13, 2008 |

Aug 21, 2008 |

Ab Science |

Process for the synthesis of 2-aminothiazole compounds as kinase inhibitors |

| EP1525200B1 |

Jul 31, 2003 |

Oct 10, 2007 |

AB Science |

2-(3-aminoaryl)amino-4-aryl-thiazoles and their use as c-kit inhibitors |

| US7423055 |

Aug 1, 2003 |

Sep 9, 2008 |

Ab Science |

2-(3-Aminoaryl)amino-4-aryl-thiazoles for the treatment of diseases |

| US20080207572 * |

Jul 13, 2006 |

Aug 28, 2008 |

Ab Science |

Use of Dual C-Kit/Fgfr3 Inhibitors for Treating Multiple Myeloma |

| Patent |

Submitted |

Granted |

| 2-(3-Aminoaryl)amino-4-aryl-thiazoles for the treatment of diseases [US7423055] |

2004-06-10 |

2008-09-09 |

| 2-(3-aminoaryl)amino-4-aryl-thiazoles and their use as c-kit inhibitors [US2005239852] |

2005-10-27 |

|

| Use of C-Kit Inhibitors for Treating Fibrosis [US2007225293] |

2007-09-27 |

|

| Use of Mast Cells Inhibitors for Treating Patients Exposed to Chemical or Biological Weapons [US2007249628] |

2007-10-25 |

|

| Use of c-kit inhibitors for treating type II diabetes [US2007032521] |

2007-02-08 |

|

| Use of tyrosine kinase inhibitors for treating cerebral ischemia [US2007191267] |

2007-08-16 |

|

| Use of C-Kit Inhibitors for Treating Plasmodium Related Diseases [US2008004279] |

2008-01-03 |

|

| Tailored Treatment Suitable for Different Forms of Mastocytosis [US2008025916] |

2008-01-31 |

|

| 2-(3-AMINOARYL) AMINO-4-ARYL-THIAZOLES AND THEIR USE AS C-KIT INHIBITORS [US2008255141] |

2008-10-16 |

|

| Use Of C-Kit Inhibitors For Treating Inflammatory Muscle Disorders Including Myositis And Muscular Dystrophy [US2008146585] |

2008-06-19 |

| Patent |

Submitted |

Granted |

| Aminothiazole compounds as kinase inhibitors and methods of using the same [US8940894] |

2013-05-10 |

2015-01-27 |

| Aminothiazole compounds as kinase inhibitors and methods of using the same [US8492545] |

2012-03-08 |

2013-07-23 |

| Patent |

Submitted |

Granted |

| Use of Dual C-Kit/Fgfr3 Inhibitors for Treating Multiple Myeloma [US2008207572] |

2008-08-28 |

| PROCESS FOR THE SYNTHESIS OF 2-AMINOTHIAZOLE COMPOUNDS AS KINASE INHIBITORS [US8153792] |

2010-05-13 |

2012-04-10 |

| COMBINATION TREATMENT OF SOLID CANCERS WITH ANTIMETABOLITES AND TYROSINE KINASE INHIBITORS [US8227470] |

2010-04-15 |

2012-07-24 |

| Anti-IGF antibodies [US8580254] |

2008-06-19 |

2013-11-12 |

| COMBINATIONS FOR THE TREATMENT OF B-CELL PROLIFERATIVE DISORDERS [US2009047243] |

2008-07-17 |

2009-02-19 |

| TREATMENTS OF B-CELL PROLIFERATIVE DISORDERS [US2009053168] |

2008-07-17 |

2009-02-26 |

| Anti-IGF antibodies [US8318159] |

2009-12-11 |

2012-11-27 |

| SURFACE TOPOGRAPHIES FOR NON-TOXIC BIOADHESION CONTROL [US2010226943] |

2009-08-31 |

2010-09-09 |

| EGFR/NEDD9/TGF-BETA INTERACTOME AND METHODS OF USE THEREOF FOR THE IDENTIFICATION OF AGENTS HAVING EFFICACY IN THE TREATMENT OF HYPERPROLIFERATIVE DISORDERS [US2010239656] |

2010-05-10 |

2010-09-23 |

| ANTI CD37 ANTIBODIES [US2010189722] |

2008-08-08 |

2010-07-29 |

United States National Library of Medicine

Note: Compound name must be entered under “Substance Identification” and then “Names and Synonyms” selected to view synonyms.

Dubreuil P, Letard S, Ciufolini M, Gros L, Humbert M, Castéran N, Borge L, Hajem B, Lermet A, Sippl W, et al.

PLoS One. 2009; 4(9):e7258. Epub 2009 Sep 30. PMID: 19789626.

Abstract

Food and Drug Administration, 15 Dec 2010

European Medicines Agency, Nov 2008

Piette F, Belmin J, Vincent H, Schmidt N, Pariel S, Verny M, Marquis C, Mely J, Hugonot-Diener L, Kinet J-P, et al.

Alzheimers Res Ther. 2011; 3(2):16. Epub 2011 Apr 19. PMID: 21504563.

Abstract

Tebib J, Mariette X, Bourgeois P, Flipo R-M, Gaudin P, Le Loët X, Gineste P, Guy L, Mansfield CD, Moussy A, et al.

Arthritis Res Ther. 2009; 11(3):R95. Epub 2009 Jun 23. PMID: 19549290.

Abstract

Businesswire.com, 6 Sep 2011

ClinicalTrials.gov, 13 Sep 2011

ClinicalTrials.gov, 10 Oct 2011

Le Cesne A, Blay J-Y, Bui B N, Bouché O, Adenis A, Domont J, Cioffi A, Ray-Coquard I, Lassau N, Bonvalot S, et al.

Eur J Cancer. 2010 May; 46(8):1344-51. Epub 2010 Mar 06. PMID: 20211560.

Abstract

Editors’ Pick

Vermersch P, Benrabah R, Schmidt N, Zéphir H, Clavelou P, Vongsouthi C, Dubreuil P, Moussy A, Hermine O

BMC Neurol. 2012 Jun 12; 12(1):36. PMID: 22691628.

Abstract

The Wall Street Journal, 4 Nov 2013

Kocic I, Kowianski P, Rusiecka I, Lietzau G, Mansfield C, Moussy A, Hermine O, Dubreuil P

Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2014 Oct 26. Epub 2014 Oct 26. PMID: 25344204.

Abstract

AB SCIENCE HEADQUARTER

AB SCIENCE HEADQUARTER

3, Avenue George V

75008 PARIS – FRANCE

Tel. : +33 (0)1 47 20 00 14

Fax. : +33 (0)1 47 20 24 11

P.S. : The views expressed are my personal and in no-way suggest the views of the professional body or the company that I represent.

P.S. : The views expressed are my personal and in no-way suggest the views of the professional body or the company that I represent.

P.S. : The views expressed are my personal and in no-way suggest the views of the professional body or the company that I represent.

TAJIKISTAN

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tajikistan

The territory that now constitutes Tajikistan was previously home to several ancient cultures, including the city of Sarazm of the Neolithic and the Bronze Age, …

.

The nature of Tajikistan. Nurek

Tajikistan. Pamiro-Alay.Zeravshan mountain range. Guzn village. Local people

Dushanbe, Tajikistan

Women carry water canisters near Gargara village, 110km south of Tajikistan’s capital, Dushanbe

Ancient Buddhist ruins, Ajina Teppa, Tajikistan

///////////

Share this:

.

.

DRUG APPROVALS BY DR ANTHONY MELVIN CRASTO …..

DRUG APPROVALS BY DR ANTHONY MELVIN CRASTO …..

.

.

.

.

ISKCON

ISKCON

.jpg)

.

.

Winners of the 2014 Elsevier Foundation Awards for Early Career Women Scientists in Developing Countries:

Winners of the 2014 Elsevier Foundation Awards for Early Career Women Scientists in Developing Countries:

.

. .

.

.

. .

. .

. .

. .

.

.

. .

.

10000 devout Hindus were present for the Hindu Dharmajagruti Sabha at Amalner, Maharashtra

10000 devout Hindus were present for the Hindu Dharmajagruti Sabha at Amalner, Maharashtra

![methanesulfonic acid,4-[(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)methyl]-N-[4-methyl-3-[(4-pyridin-3-yl-1,3-thiazol-2-yl)amino]phenyl]benzamide NMR spectra analysis, Chemical CAS NO. 1048007-93-7 NMR spectral analysis, methanesulfonic acid,4-[(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)methyl]-N-[4-methyl-3-[(4-pyridin-3-yl-1,3-thiazol-2-yl)amino]phenyl]benzamide H-NMR spectrum](http://pic11.molbase.net/nmr/nmr_image/2015-01-15/001/603/1603135_1h.png)

![methanesulfonic acid,4-[(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)methyl]-N-[4-methyl-3-[(4-pyridin-3-yl-1,3-thiazol-2-yl)amino]phenyl]benzamide NMR spectra analysis, Chemical CAS NO. 1048007-93-7 NMR spectral analysis, methanesulfonic acid,4-[(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)methyl]-N-[4-methyl-3-[(4-pyridin-3-yl-1,3-thiazol-2-yl)amino]phenyl]benzamide C-NMR spectrum](http://pic11.molbase.net/nmr/nmr_image/2015-01-15/001/603/1603135_13c.png)

In 1918-1919 between 50 and 100 million people worldwide died from the flu. The “Spanish Flu” spread to nearly every part of the world with amazing speed, helped perhaps by the thousands of soldiers returning from Europe after the end of World War I. There was little that could be done to help the sick, and often people who were healthy one day were dead the next. The Spanish Flu was remarkable at the time in that it primarily killed young healthy adults, whereas most often it is very young children and elderly people who die from infectious disease.

In 1918-1919 between 50 and 100 million people worldwide died from the flu. The “Spanish Flu” spread to nearly every part of the world with amazing speed, helped perhaps by the thousands of soldiers returning from Europe after the end of World War I. There was little that could be done to help the sick, and often people who were healthy one day were dead the next. The Spanish Flu was remarkable at the time in that it primarily killed young healthy adults, whereas most often it is very young children and elderly people who die from infectious disease.

SUVA

SUVA

The Treasure Island Resort Lunch Tour is a great option for your next Fiji itinerary.

The Treasure Island Resort Lunch Tour is a great option for your next Fiji itinerary.