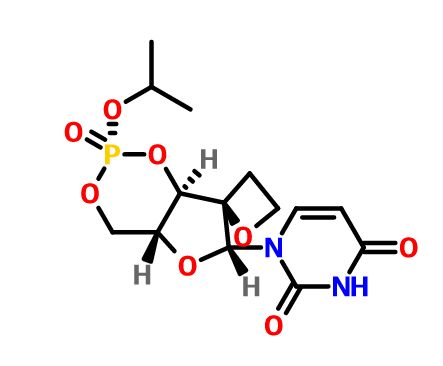

JNJ-54257099,

1-((2R,4aR,6R,7R,7aR)-2-Isopropoxy-2-oxidodihydro-4H,6H-spiro[furo[3,2-d][1,3,2]dioxaphosphinine-7,2′-oxetan]-6-yl)pyrimidine-2,4(1H,3H)-dione

MW 374.28, C14 H19 N2 O8 P

CAS 1491140-67-0

2,4(1H,3H)-Pyrimidinedione, 1-[(2R,2′R,4aR,6R,7aR)-dihydro-2-(1-methylethoxy)-2-oxidospiro[4H-furo[3,2-d]-1,3,2-dioxaphosphorin-7(6H),2′-oxetan]-6-yl]-

1-((2R,4aR,6R,7R,7aR)-2-Isopropoxy-2-oxidodihydro-4H,6H-spiro[furo[3,2-d][1,3,2]dioxaphos-phinine-7,2′-oxetan]-6-yl)pyrimidine-2,4(1H,3H)-dione

Janssen R&D Ireland INNOVATOR

Ioannis Nicolaos Houpis, Tim Hugo Maria Jonckers, Pierre Jean-Marie Bernard Raboisson, Abdellah Tahri,

Tim Jonckers was born in Antwerp in 1974. He studied Chemistry at the University of Antwerp and obtained his Ph.D. in organic chemistry in 2002. His Ph.D. work covered the synthesis of new necryptolepine derivatives which have potential antimalarial activity. Currently he works as a Senior Scientist at Tibotec, a pharmaceutical research and development company based in Mechelen, Belgium, that focuses on viral diseases mainly AIDS and hepatitis. The company was acquired by Johnson & Johnson in April 2002 and recently gained FDA approval for its HIV-protease inhibitor PREZISTA™.

Principal Scientist at Janssen, Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson and Johnson

DATA

Chiral SFC using the methods described(Method 1, Rt= 5.12 min, >99%; Method 2, Rt = 7.95 min, >99%).

1H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d) δ ppm 1.45 (dd, J = 7.53, 6.27 Hz, 6 H), 2.65–2.84 (m, 2 H), 3.98 (td, J = 10.29, 4.77 Hz, 1 H), 4.27 (t,J = 9.66 Hz, 1 H), 4.43 (ddd, J = 8.91, 5.77, 5.65 Hz, 1 H), 4.49–4.61 (m, 1 H), 4.65 (td, J = 7.78, 5.77 Hz, 1 H), 4.73 (d, J = 7.78 Hz, 1 H), 4.87 (dq, J = 12.74, 6.30 Hz, 1 H), 5.55 (br. s., 1 H), 5.82 (d, J = 8.03 Hz, 1 H), 7.20 (d, J = 8.03 Hz, 1 H), 8.78 (br. s., 1 H);

31P NMR (chloroform-d) δ ppm −7.13. LC-MS: 375 (M + H)+.

HCV is a single stranded, positive-sense R A virus belonging to the Flaviviridae family of viruses in the hepacivirus genus. The NS5B region of the RNA polygene encodes a RNA dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), which is essential to viral replication. Following the initial acute infection, a majority of infected individuals develop chronic hepatitis because HCV replicates preferentially in hepatocytes but is not directly cytopathic. In particular, the lack of a vigorous T-lymphocyte response and the high propensity of the virus to mutate appear to promote a high rate of chronic infection. Chronic hepatitis can progress to liver fibrosis, leading to cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease, and HCC (hepatocellular carcinoma), making it the leading cause of liver transplantations. There are six major HCV genotypes and more than 50 subtypes, which are differently distributed geographically. HCV genotype 1 is the predominant genotype in Europe and in the US. The extensive genetic heterogeneity of HCV has important diagnostic and clinical implications, perhaps explaining difficulties in vaccine development and the lack of response to current therapy.

Transmission of HCV can occur through contact with contaminated blood or blood products, for example following blood transfusion or intravenous drug use. The introduction of diagnostic tests used in blood screening has led to a downward trend in post-transfusion HCV incidence. However, given the slow progression to the end-stage liver disease, the existing infections will continue to present a serious medical and economic burden for decades.

Therapy possibilities have extended towards the combination of a HCV protease inhibitor (e.g. Telaprevir or boceprevir) and (pegylated) interferon-alpha (IFN-a) / ribavirin. This combination therapy has significant side effects and is poorly tolerated in many patients. Major side effects include influenza-like symptoms, hematologic

abnormalities, and neuropsychiatric symptoms. Hence there is a need for more effective, convenient and better-tolerated treatments.

The NS5B RdRp is essential for replication of the single-stranded, positive sense, HCV RNA genome. This enzyme has elicited significant interest among medicinal chemists. Both nucleoside and non-nucleoside inhibitors of NS5B are known. Nucleoside inhibitors can act as a chain terminator or as a competitive inhibitor, or as both. In order to be active, nucleoside inhibitors have to be taken up by the cell and converted in vivo to a triphosphate. This conversion to the triphosphate is commonly mediated by cellular kinases, which imparts additional structural requirements on a potential nucleoside polymerase inhibitor. In addition this limits the direct evaluation of nucleosides as inhibitors of HCV replication to cell-based assays capable of in situ phosphorylation.

Several attempts have been made to develop nucleosides as inhibitors of HCV RdRp, but while a handful of compounds have progressed into clinical development, none have proceeded to registration. Amongst the problems which HCV-targeted

nucleosides have encountered to date are toxicity, mutagenicity, lack of selectivity, poor efficacy, poor bioavailability, sub-optimal dosage regimes and ensuing high pill burden and cost of goods.

Spirooxetane nucleosides, in particular l-(8-hydroxy-7-(hydroxy- methyl)- 1,6-dioxaspiro[3.4]octan-5-yl)pyrimidine-2,4-dione derivatives and their use as HCV inhibitors are known from WO2010/130726, and WO2012/062869, including

CAS-1375074-52-4.

There is a need for HCV inhibitors that may overcome at least one of the disadvantages of current HCV therapy such as side effects, limited efficacy, the emerging of resistance, and compliance failures, or improve the sustained viral response.

The present invention concerns HCV-inhibiting uracyl spirooxetane derivatives with useful properties regarding one or more of the following parameters: antiviral efficacy towards at least one of the following genotypes la, lb, 2a, 2b, 3,4 and 6, favorable

profile of resistance development, lack of toxicity and genotoxicity, favorable pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics and ease of formulation and administration.

Such an HCV-inhibiting uracyl spirooxetane derivative is a compound with formula I

including any pharmaceutically acceptable salt or solvate thereof.

PATENT

WO 2015077966

https://www.google.com/patents/WO2015077966A1?cl=en

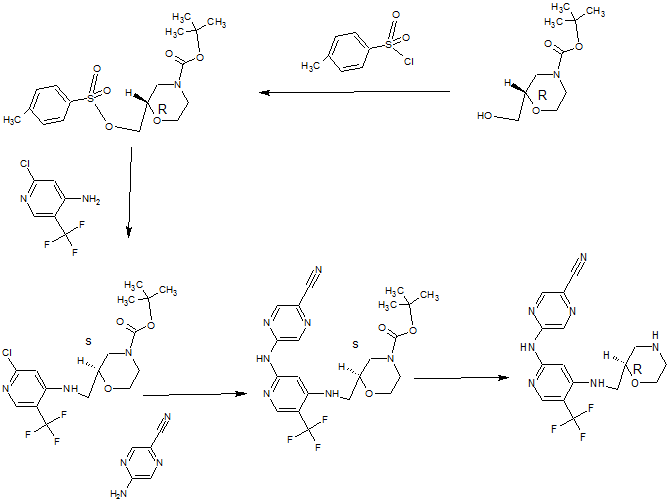

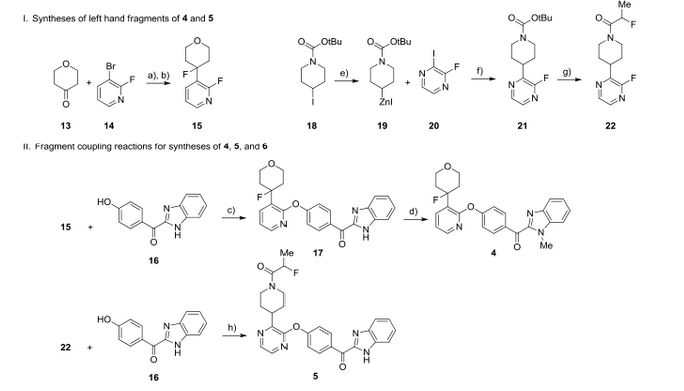

Synthesis of compound (I)

(5) (6a)

Synthesis of compound (6a)

A solution of isopropyl alcohol (3.86 mL,0.05mol) and triethylamine (6.983 mL, 0.05mol) in dichloromethane (50 mL) was added to a stirred solution of POCI3 (5)

(5.0 mL, 0.055 lmol) in DCM (50 mL) dropwise over a period of 25 min at -5°C. After the mixture stirred for lh, the solvent was evaporated, and the residue was suspended in ether (100 mL). The triethylamine hydrochloride salt was filtered and washed with ether (20 mL). The filtrate was concentrated, and the residue was distilled to give the (6) as a colorless liquid (6.1g, 69 %yield).

Synthesis of compound (4):

CAS 1255860-33-3 is dissolved in pyridine and 1,3-dichloro-l, 1,3,3-tetraisopropyldisiloxane is added. The reaction is stirred at room temperature until complete. The solvent is removed and the product redissolved in CH2CI2 and washed with saturated NaHC03 solution. Drying on MgSC^ and removal of the solvent gives compound (2). Compound (3) is prepared by reacting compound (2) with p-methoxybenzylchloride in the presence of DBU as the base in CH3CN. Compound (4) is prepared by cleavage of the bis-silyl protecting group in compound (3) using TBAF as the fluoride source.

Synthesis of compound (7a)

To a stirred suspension of (4) (2.0 g, 5.13 mmol) in dichloromethane (50 mL) was added triethylamine (2.07 g, 20.46 mmol) at room temperature. The reaction mixture was cooled to -20°C, and then (6a) (1.2 g, 6.78mmol) was added dropwise over a period of lOmin. The mixture was stirred at this temperature for 15min and then NMI was added (0.84 g, 10.23 mmol), dropwise over a period of 15 min. The mixture was stirred at -15°C for lh and then slowly warmed to room temperature in 20 h. The solvent was evaporated, the mixture was concentrated and purified by column chromatography using petroleum ether/EtOAc (10: 1 to 5: 1 as a gradient) to give (7a) as white solid (0.8 g, 32 % yield).

Synthesis of compound (I)

To a solution of (7a) in CH3CN (30 mL) and H20 (7 mL) was add CAN portion wise below 20° C. The mixture was stirred at 15-20° C for 5h under N2. Na2S03 (370 mL) was added dropwise into the reaction mixture below 15°C, and then Na2C03 (370 mL) was added. The mixture was filtered and the filtrate was extracted with CH2C12

(100 mL*3). The organic layer was dried and concentrated to give the residue. The residue was purified by column chromatography to give the target compound (8a) as white solid. (Yield: 55%)

1H NMR (400 MHz, CHLOROFORM- ) δ ppm 1.45 (dd, J=7.53, 6.27 Hz, 6 H), 2.65 -2.84 (m, 2 H), 3.98 (td, J=10.29, 4.77 Hz, 1 H), 4.27 (t, J=9.66 Hz, 1 H), 4.43 (ddd, J=8.91, 5.77, 5.65 Hz, 1 H), 4.49 – 4.61 (m, 1 H), 4.65 (td, J=7.78, 5.77 Hz, 1 H), 4.73 (d, J=7.78 Hz, 1 H), 4.87 (dq, J=12.74, 6.30 Hz, 1 H), 5.55 (br. s., 1 H), 5.82 (d, J=8.03 Hz, 1 H), 7.20 (d, J=8.03 Hz, 1 H), 8.78 (br. s., 1 H); 31P NMR (CHLOROFORM-^) δ ppm -7.13; LC-MS: 375 (M+l)+

PATENT

https://www.google.co.in/patents/WO2013174962A1?cl=en

The starting material l-[(4R,5R,7R,8R)-8-hydroxy-7-(hydroxymethyl)-l,6-dioxa- spiro[3.4]octan-5-yl]pyrimidine-2,4(lH,3H)-dione (1) can be prepared as exemplified in WO2010/130726. Compound (1) is converted into compounds of the present invention via a p-methoxybenzyl protected derivative (4) as exemplified in the following Scheme 1. cheme 1

Examples

Scheme 2

Synthesis of compound (8a)

Synthesis of compound (2)

Compound (2) can be prepared by dissolving compound (1) in pyridine and adding l,3-dichloro-l,l,3,3-tetraisopropyldisiloxane. The reaction is stirred at room temperature until complete. The solvent is removed and the product redissolved in CH2CI2and washed with saturated NaHC03 solution. Drying on MgSC^ and removal of the solvent gives compound (2).

Synthesis of compound (3)

Compound (3) is prepared by reacting compound (2) with p-methoxybenzylchloride in the presence of DBU as the base in CH3CN.

Synthesis of compound (4)

Compound (4) is prepared by cleavage of the bis-silyl protecting group in compound (3) using TBAF as the fluoride source.

Synthesis of compound (6a)

A solution of isopropyl alcohol (3.86 mL,0.05mol) and triethylamine (6.983 mL, 0.05mol) in dichloromethane (50 mL) was added to a stirred solution of POCl3 (5) (5.0 mL, 0.055 lmol) in DCM (50 mL) dropwise over a period of 25 min at -5°C. After the mixture stirred for lh, the solvent was evaporated, and the residue was suspended in ether (100 mL). The triethylamine hydrochloride salt was filtered and washed with ether (20 mL). The filtrate was concentrated, and the residue was distilled to give the (6) as a colorless liquid (6.1g, 69 %yield).

Synthesis of compound (7a)

To a stirred suspension of (4) (2.0 g, 5.13 mmol) in dichloromethane (50 mL) was added triethylamine (2.07 g, 20.46 mmol) at room temperature. The reaction mixture was cooled to -20°C, and then (6a) (1.2 g, 6.78mmol) was added dropwise over a period of lOmin. The mixture was stirred at this temperature for 15min and then NMI was added (0.84 g, 10.23 mmol), dropwise over a period of 15 min. The mixture was stirred at -15°C for lh and then slowly warmed to room temperature in 20 h. The solvent was evaporated, the mixture was concentrated and purified by column chromatography using petroleum ether/EtOAc (10:1 to 5: 1 as a gradient) to give (7a) as white solid (0.8 g, 32 % yield).

Synthesis of compound (8a)

To a solution of (7a) in CH3CN (30 mL) and H20 (7 mL) was add CAN portion wise below 20°C. The mixture was stirred at 15-20°C for 5h under N2. Na2S03 (370 mL) was added dropwise into the reaction mixture below 15°C, and then Na2C03 (370 mL) was added. The mixture was filtered and the filtrate was extracted with CH2C12

(100 mL*3). The organic layer was dried and concentrated to give the residue. The residue was purified by column chromatography to give the target compound (8a) as white solid. (Yield: 55%)

1H NMR (400 MHz, CHLOROFORM- ) δ ppm 1.45 (dd, J=7.53, 6.27 Hz, 6 H), 2.65 – 2.84 (m, 2 H), 3.98 (td, J=10.29, 4.77 Hz, 1 H), 4.27 (t, J=9.66 Hz, 1 H), 4.43 (ddd, J=8.91, 5.77, 5.65 Hz, 1 H), 4.49 – 4.61 (m, 1 H), 4.65 (td, J=7.78, 5.77 Hz, 1 H), 4.73 (d, J=7.78 Hz, 1 H), 4.87 (dq, J=12.74, 6.30 Hz, 1 H), 5.55 (br. s., 1 H), 5.82 (d, J=8.03 Hz, 1 H), 7.20 (d, J=8.03 Hz, 1 H), 8.78 (br. s., 1 H); 31P NMR (CHLOROFORM-^) δ ppm -7.13; LC-MS: 375 (M+l)+ Scheme 3

Synthesis of compound (VI)

Step 1: Synthesis of compound (9)Compound (1), CAS 1255860-33-3 ( 1200 mg, 4.33 mmol ) and l,8-bis(dimethyl- amino)naphthalene (3707 mg, 17.3 mmol) were dissolved in 24.3 mL of

trimethylphosphate. The solution was cooled to 0°C. Compound (5) (1.21 mL, 12.98 mmol) was added, and the mixture was stirred well maintaining the temperature at 0°C for 5 hours. The reaction was quenched by addition of 120 mL of tetraethyl- ammonium bromide solution (1M) and extracted with CH2CI2 (2×80 mL). Purification was done by preparative HPLC (Stationary phase: RP XBridge Prep CI 8 ΟΒϋ-10μιη, 30x150mm, mobile phase: 0.25% NH4HCO3 solution in water, CH3CN) , yielding two fractions. The purest fraction was dissolved in water (15 mL) and passed through a manually packed Dowex (H+) column by elution with water. The end of the elution was determined by checking UV absorbance of eluting fractions. Combined fractions were frozen at -78°C and lyophilized. Compound (9) was obtained as a white fluffy solid (303 mg, (0.86 mmol, 20%> yield), which was used immediately in the following reaction. Step 2: Preparation of compound (VI)

Compound (9) (303 mg, 0.86 mmol) was dissolved in 8 mL water and to this solution was added N . N’- D ic y c ! he y !-4- mo rph line carboxamidine (253.8 mg, 0.86 mmol) dissolved in pyridine (8.4 mi.). The mixture was kept for 5 minutes and then

evaporated to dryness, dried overnight in vacuo overnight at 37°C. The residu was dissolved in pyridine (80 mL). This solution was added dropwise to vigorously stirred DCC (892.6 mg, 4.326 mmol) in pyridine (80 mL) at reflux temperature. The solution was kept refluxing for 1.5h during which some turbidity was observed in the solution. The reaction mixture was cooled and evaporated to dryness. Diethylether (50 mL) and water (50 mL) were added to the solid residu. N’N-dicyclohexylurea was filtered off, and the aqueous fraction was purified by preparative HPLC (Stationary phase: RP XBridge Prep C18 OBD-ΙΟμιη, 30x150mm, mobile phase: 0.25% NH4HCO3 solution in water, CH3CN) , yielding a white solid which was dried overnight in vacuo at 38°C. (185 mg, 0.56 mmol, 65% yield). LC-MS: (M+H)+: 333.

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) d ppm 2.44 – 2.59 (m, 2 H) signal falls under DMSO signal, 3.51 (td, J=9.90, 5.50 Hz, 1 H), 3.95 – 4.11 (m, 2 H), 4.16 (d, J=10.34 Hz, 1 H), 4.25 – 4.40 (m, 2 H), 5.65 (d, J=8.14 Hz, 1 H), 5.93 (br. s., 1 H), 7.46 (d, J=7.92 Hz, 1 H), 2H’s not observed

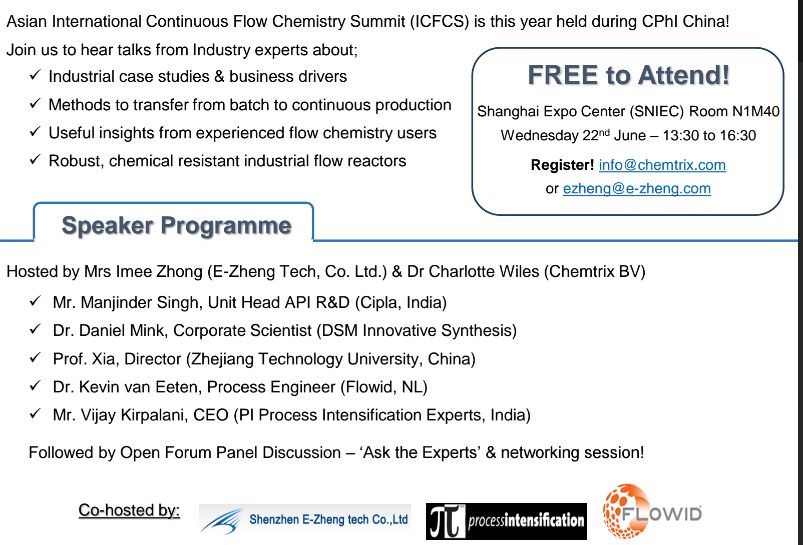

Paper

http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00382,

Discovery of 1-((2R,4aR,6R,7R,7aR)-2-Isopropoxy-2-oxidodihydro-4H,6H-spiro[furo[3,2-d][1,3,2]dioxaphosphinine-7,2′-oxetan]-6-yl)pyrimidine-2,4(1H,3H)-dione (JNJ-54257099), a 3′-5′-Cyclic Phosphate Ester Prodrug of 2′-Deoxy-2′-Spirooxetane Uridine Triphosphate Useful for HCV Inhibition

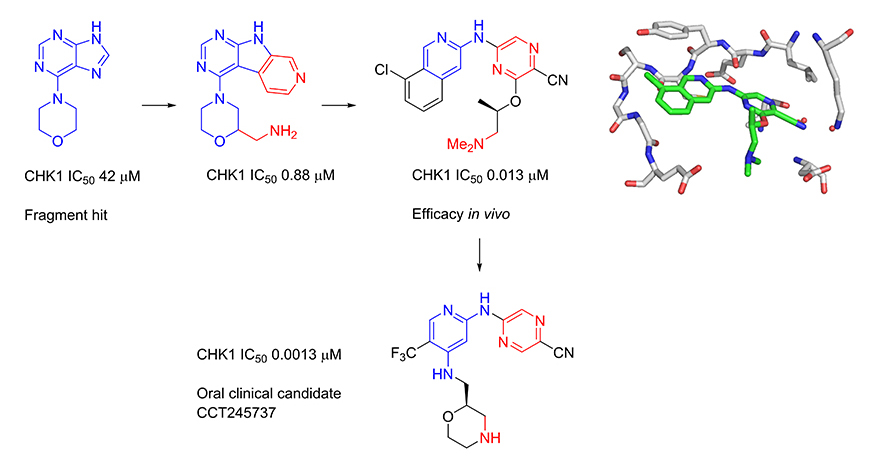

JNJ-54257099 (9) is a novel cyclic phosphate ester derivative that belongs to the class of 2′-deoxy-2′-spirooxetane uridine nucleotide prodrugs which are known as inhibitors of the HCV NS5B RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp). In the Huh-7 HCV genotype (GT) 1b replicon-containing cell line 9 is devoid of any anti-HCV activity, an observation attributable to inefficient prodrug metabolism which was found to be CYP3A4-dependent. In contrast, in vitro incubation of 9 in primary human hepatocytes as well as pharmacokinetic evaluation thereof in different preclinical species reveals the formation of substantial levels of 2′-deoxy-2′-spirooxetane uridine triphosphate (8), a potent inhibitor of the HCV NS5B polymerase. Overall, it was found that 9 displays a superior profile compared to its phosphoramidate prodrug analogues (e.g., 4) described previously. Of particular interest is the in vivo dose dependent reduction of HCV RNA observed in HCV infected (GT1a and GT3a) human hepatocyte chimeric mice after 7 days of oral administration of 9

////////////JNJ-54257099, 1491140-67-0, JNJ54257099, JNJ 54257099

O=C(C=C1)NC(N1[C@H]2[C@]3(OCC3)[C@H](O4)[C@@H](CO[P@@]4(OC(C)C)=O)O2)=O

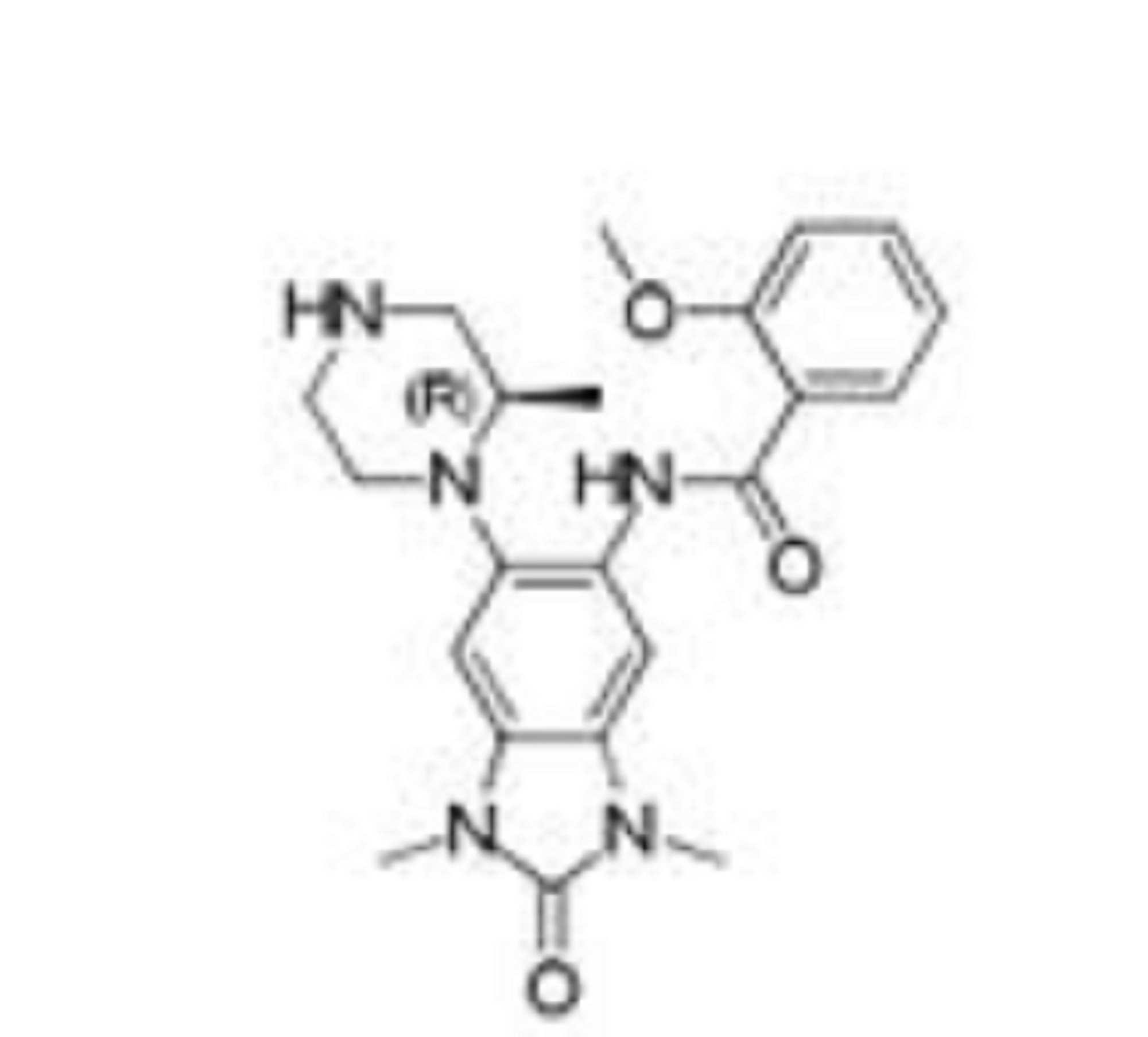

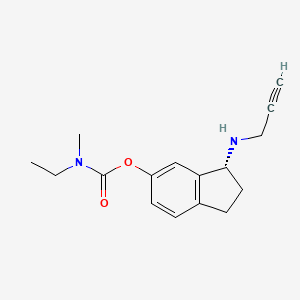

(R)-3-(Prop-2-ynylamino)-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-5-yl ethyl(methyl)carbamate

(R)-3-(Prop-2-ynylamino)-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-5-yl ethyl(methyl)carbamate

(R)-3-(Prop-2-ynylamino)-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-5-yl ethyl(methyl)carbamate hemi((2R,3R)-2,3-dihydroxysuccinate)

(R)-3-(Prop-2-ynylamino)-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-5-yl ethyl(methyl)carbamate hemi((2R,3R)-2,3-dihydroxysuccinate)