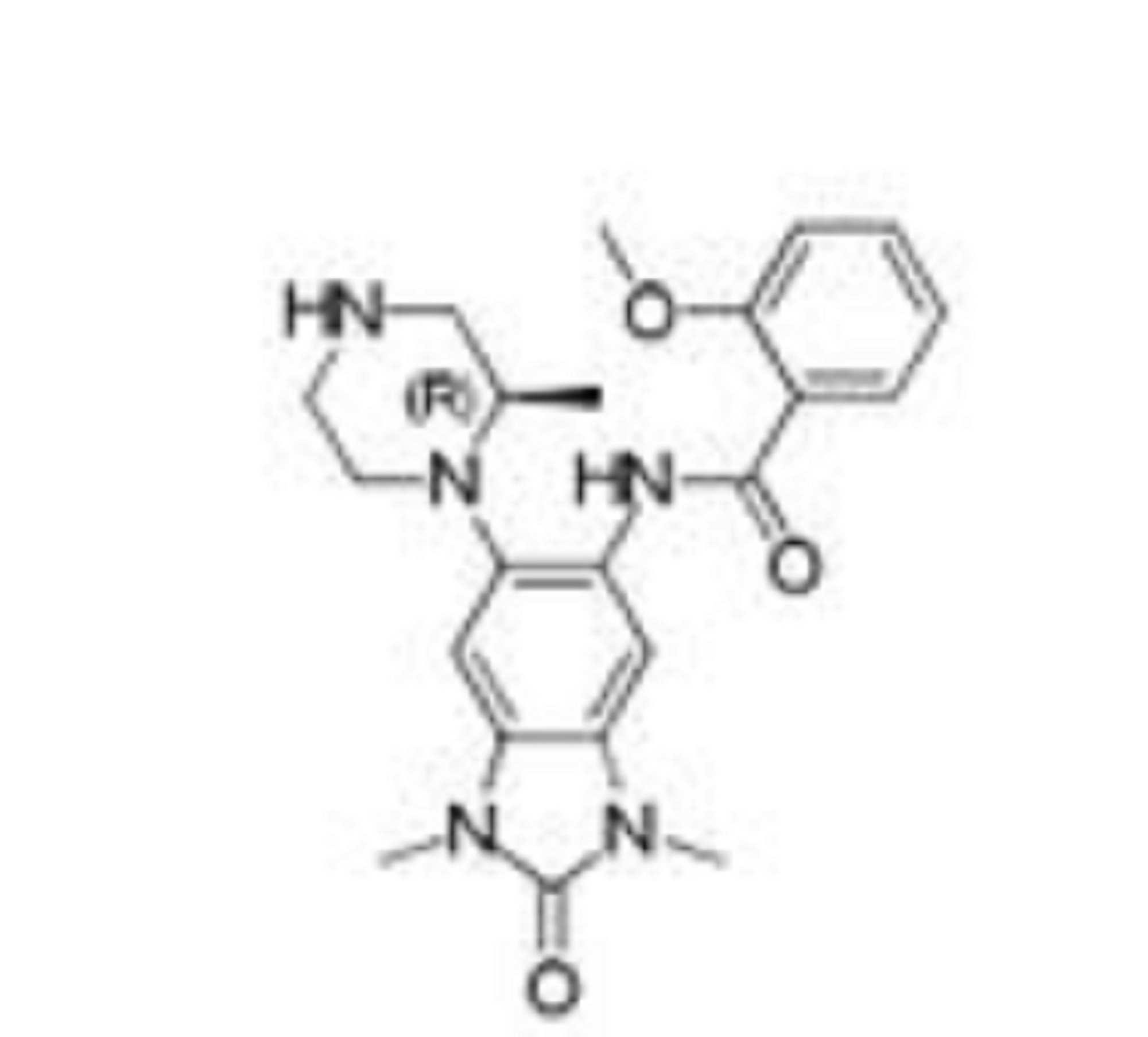

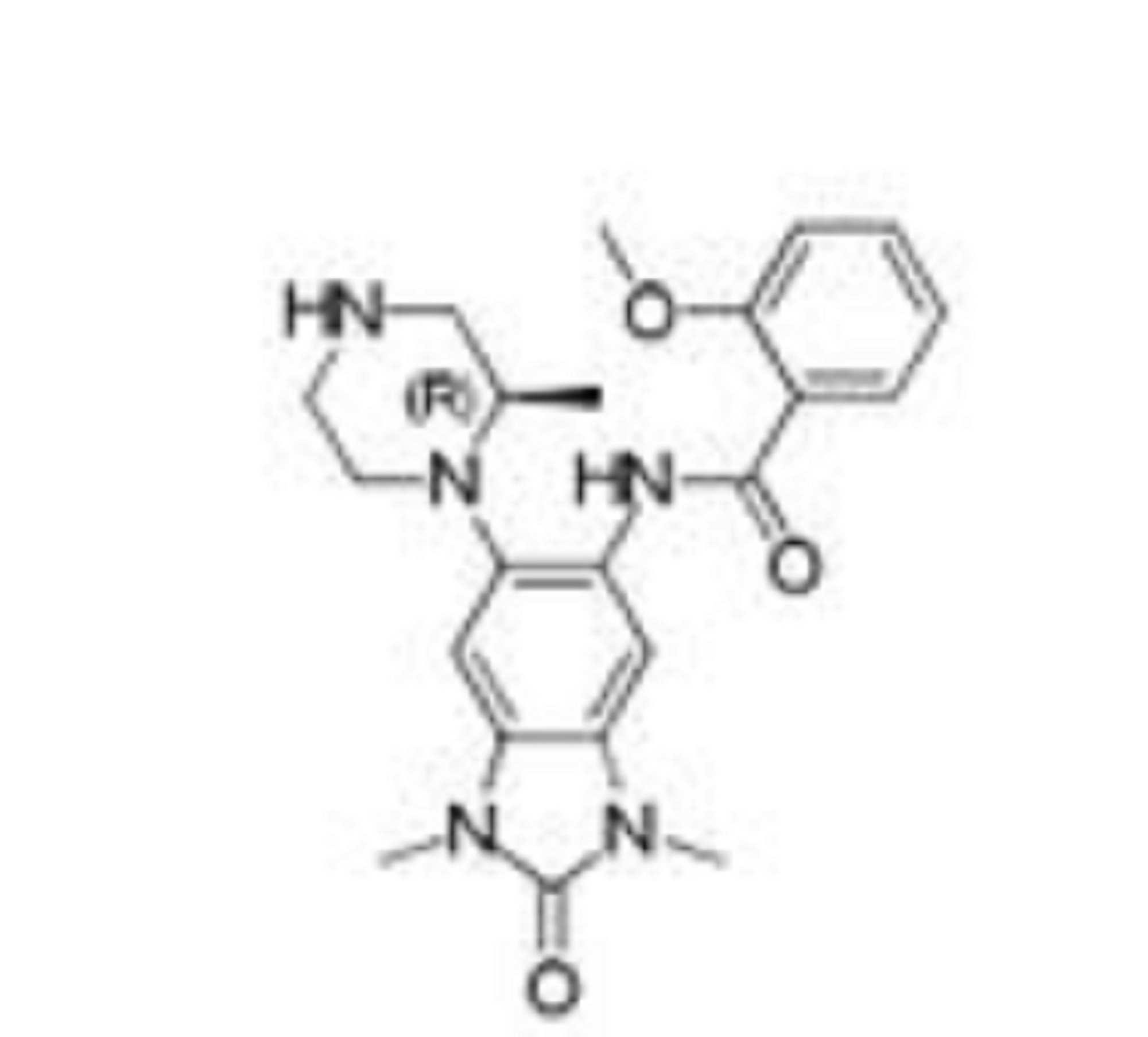

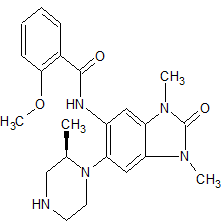

GSK 6853

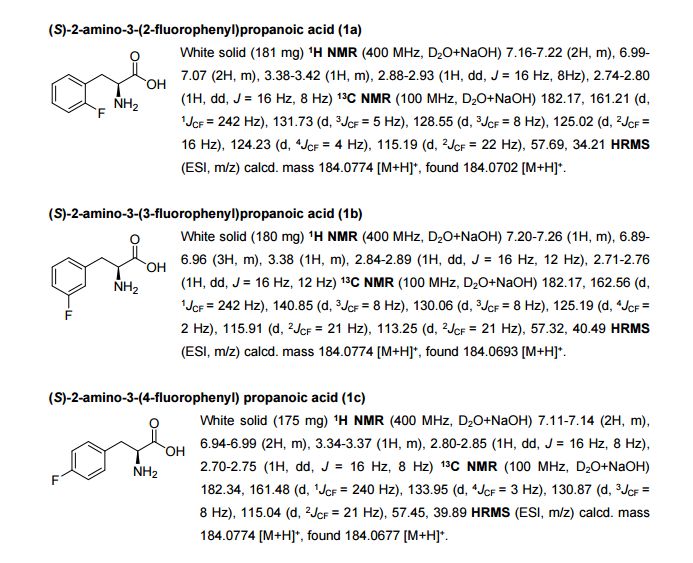

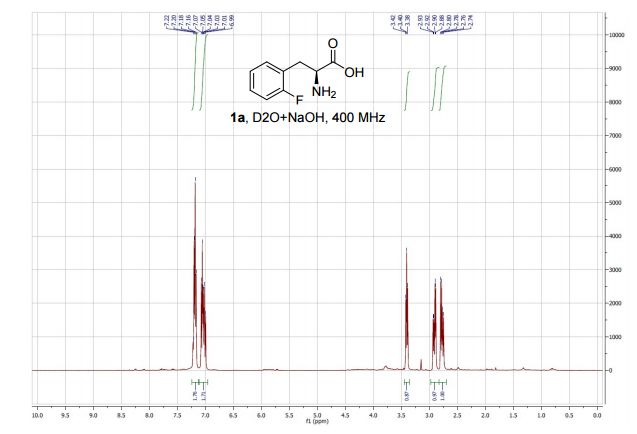

CAS 1910124-24-1

C22 H27 N5 O3, 409.48

Benzamide, N-[2,3-dihydro-1,3-dimethyl-6-[(2R)-2-methyl-1-piperazinyl]-2-oxo-1H-benzimidazol-5-yl]-2-methoxy-

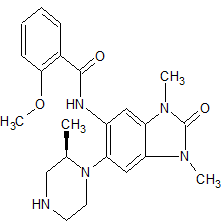

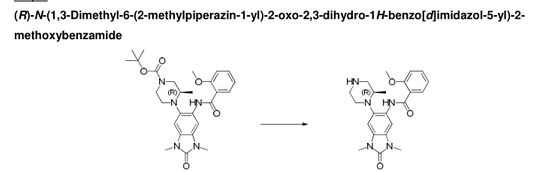

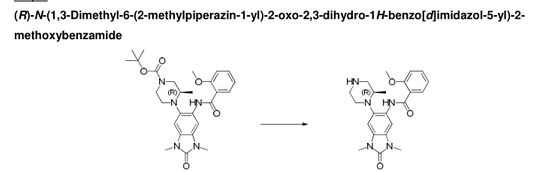

(R)-N-(1 ,3- dimethyl-6-(2-methylpiperazin-1 -yl)-2-oxo-2,3-dihydro-1 H-benzo[d]imidazol-5-yl)-2- methoxybenzamide

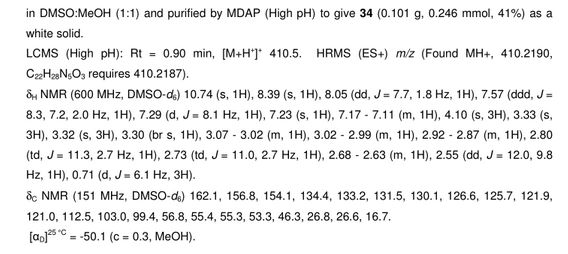

A white solid.

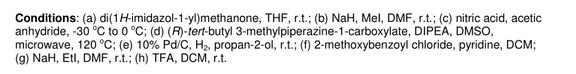

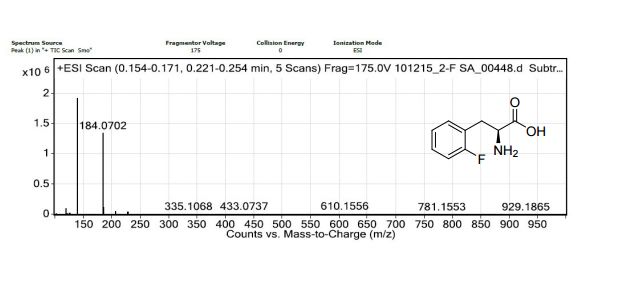

LCMS (high pH): Rt = 0.90 min, [M+H+]+ 410.5.

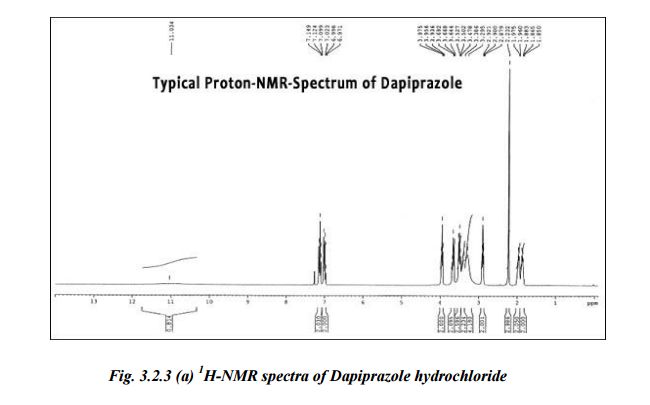

δΗ NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) ppm 10.74 (s, 1 H), 8.39 (s, 1 H), 8.05 (dd, J = 7.7, 1.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.57 (ddd, J = 8.3, 7.2, 2.0 Hz, 1 H), 7.29 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1 H), 7.23 (s, 1 H), 7.17-7.1 1 (m, 1 H), 4.10 (s, 3H), 3.33 (s, 3H), 3.32 (s, 3H), 3.30 (br s, 1 H), 3.07-3.02 (m, 1 H), 3.02-2.99 (m, 1 H), 2.92-2.87 (m, 1 H), 2.80 (td, J = 1 1.3, 2.7 Hz, 1 H), 2.73 (td, J = 1 1 .0, 2.7 Hz, 1 H), 2.68-2.63 (m, 1 H), 2.55 (dd, J = 12.0, 9.8 Hz, 1 H), 0.71 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 3H).

δ0 NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) ppm 162.1 , 156.8, 154.1 , 134.4, 133.2, 131.5, 130.1 , 126.6, 125.7, 121.9, 121.0, 1 12.5, 103.0, 99.4, 56.8, 55.4, 55.3, 53.3, 46.3, 26.8, 26.6, 16.7.

[aD]25 °c = -50.1 (c = 0.3, MeOH).

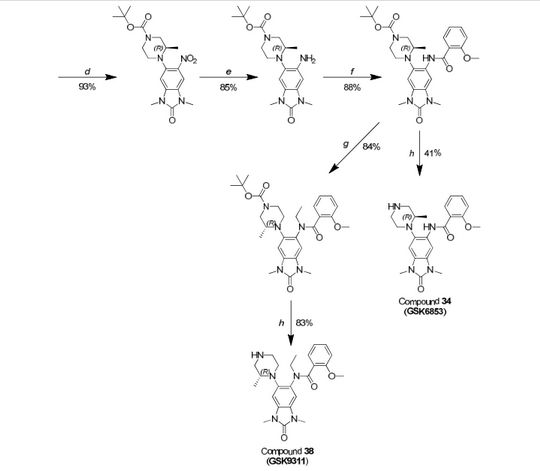

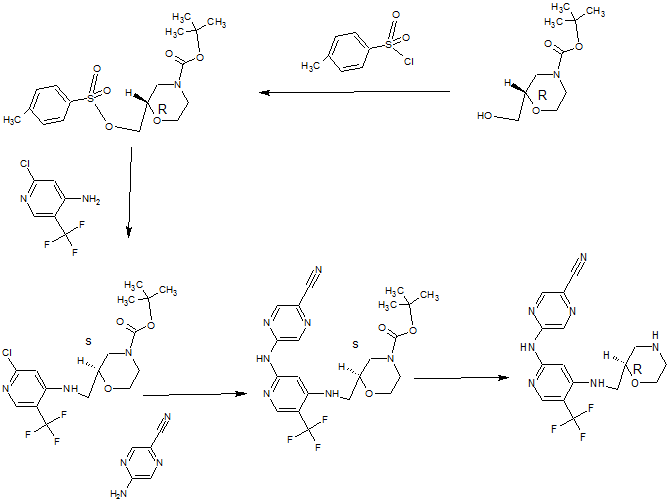

Scheme 1

The genomes of eukaryotic organisms are highly organised within the nucleus of the cell. The long strands of duplex DNA are wrapped around an octomer of histone proteins (most usually comprising two copies of histones H2A, H2B, H3 and H4) to form a

nucleosome. This basic unit is then further compressed by the aggregation and folding of nucleosomes to form a highly condensed chromatin structure. A range of different states of condensation are possible, and the tightness of this structure varies during the cell cycle, being most compact during the process of cell division. Chromatin structure plays a critical role in regulating gene transcription, which cannot occur efficiently from highly condensed chromatin. The chromatin structure is controlled by a series of post-translational

modifications to histone proteins, notably histones H3 and H4, and most commonly within the histone tails which extend beyond the core nucleosome structure. These modifications include acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitinylation, SUMOylation and numerous others. These epigenetic marks are written and erased by specific enzymes, which place the tags on specific residues within the histone tail, thereby forming an epigenetic code, which is then interpreted by the cell to allow gene specific regulation of chromatin structure and thereby transcription.

Histone acetylation is usually associated with the activation of gene transcription, as the modification loosens the interaction of the DNA and the histone octomer by changing the electrostatics. In addition to this physical change, specific proteins bind to acetylated lysine residues within histones to read the epigenetic code. Bromodomains are small (=1 10 amino acid) distinct domains within proteins that bind to acetylated lysine residues commonly but not exclusively in the context of histones. There is a family of around 50 proteins known to contain bromodomains, and they have a range of functions within the cell.

BRPF1 (also known as peregrin or Protein Br140) is a bromodomain-containing protein that has been shown to bind to acetylated lysine residues in histone tails, including H2AK5ac, H4K12ac and H3K14ac (Poplawski et al, J. Mol. Biol., 2014 426: 1661-1676). BRPF1 also contains several other domains typically found in chromatin-associated factors, including a double plant homeodomain (PHD) and zinc finger (ZnF) assembly (PZP), and a chromo/Tudor-related Pro-Trp-Trp-Pro (PWWP) domain. BRPF1 forms a tetrameric complex with monocytic leukemia zinc-finger protein (MOZ, also known as KAT6A or MYST3) inhibitor of growth 5 (ING5) and homolog of Esa1 -associated factor (hEAF6). In humans, the t(8;16)(p1 1 ;p13) translocation of MOZ (monocytic leukemia zinc-finger protein, also known as KAT6A or MYST3) is associated with a subtype of acute myeloid leukemia and

contributes to the progression of this disease (Borrow et al, Nat. Genet., 1996 14: 33-41 ). The BRPF1 bromodomain contributes to recruiting the MOZ complex to distinct sites of active chromatin and hence is considered to play a role in the function of MOZ in regulating transcription, hematopoiesis, leukemogenesis, and other developmental processes (Ullah et al, Mol. Cell. Biol., 2008 28: 6828-6843; Perez-Campo et al, Blood, 2009 1 13: 4866-4874). Demont et al, ACS Med. Chem. Lett., (2014) (dx.doi.org/10.1021/ml5002932), discloses certain 1 ,3-dimethyl benzimidazolones as potent, selective inhibitors of the BRPF1 bromodomain.

BRPF1 bromodomain inhibitors, and thus are believed to have potential utility in the treatment of diseases or conditions for which a bromodomain inhibitor is indicated. Bromodomain inhibitors are believed to be useful in the treatment of a variety of diseases or conditions related to systemic or tissue inflammation, inflammatory responses to infection or hypoxia, cellular activation and proliferation, lipid metabolism, fibrosis and in the prevention and treatment of viral infections. Bromodomain inhibitors may be useful in the treatment of a wide variety of chronic autoimmune and inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, psoriasis, systemic lupus erythematosus, multiple sclerosis, inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis), asthma, chronic obstructive airways disease, pneumonitis, myocarditis, pericarditis, myositis, eczema, dermatitis (including atopic dermatitis), alopecia, vitiligo, bullous skin diseases, nephritis, vasculitis, atherosclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, depression, Sjogren’s syndrome, sialoadenitis, central retinal vein occlusion, branched retinal vein occlusion, Irvine-Gass syndrome (post-cataract and post-surgical), retinitis pigmentosa, pars planitis, birdshot retinochoroidopathy, epiretinal membrane, cystic macular edema, parafoveal telengiectasis, tractional maculopathies, vitreomacular traction syndromes, retinal detachment,

neuroretinitis, idiopathic macular edema, retinitis, dry eye (kerartoconjunctivitis Sicca), vernal keratoconjunctivitis, atopic keratoconjunctivitis, uveitis (such as anterior uveitis, pan uveitis, posterior uveits, uveitis-associated macula edema), scleritis, diabetic retinopathy, diabetic macula edema, age-related macula dystrophy, hepatitis, pancreatitis, primary biliary cirrhosis, sclerosing cholangitis, Addison’s disease, hypophysitis, thyroiditis, type I diabetes, type 2 diabetes and acute rejection of transplanted organs. Bromodomain inhibitors may be useful in the treatment of a wide variety of acute inflammatory conditions such as acute gout, nephritis including lupus nephritis, vasculitis with organ involvement such as

glomerulonephritis, vasculitis including giant cell arteritis, Wegener’s granulomatosis, Polyarteritis nodosa, Behcet’s disease, Kawasaki disease, Takayasu’s Arteritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, vasculitis with organ involvement and acute rejection of transplanted organs. Bromodomain inhibitors may be useful in the treatment of diseases or conditions which involve inflammatory responses to infections with bacteria, viruses, fungi, parasites or their toxins, such as sepsis, sepsis syndrome, septic shock, endotoxaemia, systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), multi-organ dysfunction syndrome, toxic shock syndrome, acute

lung injury, ARDS (adult respiratory distress syndrome), acute renal failure, fulminant hepatitis, burns, acute pancreatitis, post-surgical syndromes, sarcoidosis, Herxheimer reactions, encephalitis, myelitis, meningitis, malaria and SIRS associated with viral infections such as influenza, herpes zoster, herpes simplex and coronavirus. Bromodomain inhibitors may be useful in the treatment of conditions associated with ischaemia-reperfusion injury such as myocardial infarction, cerebro-vascular ischaemia (stroke), acute coronary syndromes, renal reperfusion injury, organ transplantation, coronary artery bypass grafting, cardio-pulmonary bypass procedures, pulmonary, renal, hepatic, gastro-intestinal or peripheral limb embolism. Bromodomain inhibitors may be useful in the treatment of disorders of lipid metabolism via the regulation of APO-A1 such as hypercholesterolemia, atherosclerosis and Alzheimer’s disease. Bromodomain inhibitors may be useful in the treatment of fibrotic conditions such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, renal fibrosis, postoperative stricture, keloid scar formation, scleroderma (including morphea) and cardiac fibrosis. Bromodomain inhibitors may be useful in the treatment of a variety of diseases associated with bone remodelling such as osteoporosis, osteopetrosis, pycnodysostosis, Paget’s disease of bone, familial expanile osteolysis, expansile skeletal hyperphosphatasia, hyperososis corticalis deformans Juvenilis, juvenile Paget’s disease and Camurati

Engelmann disease. Bromodomain inhibitors may be useful in the treatment of viral infections such as herpes virus, human papilloma virus, adenovirus and poxvirus and other DNA viruses. Bromodomain inhibitors may be useful in the treatment of cancer, including hematological (such as leukaemia, lymphoma and multiple myeloma), epithelial including lung, breast and colon carcinomas, midline carcinomas, mesenchymal, hepatic, renal and neurological tumours. Bromodomain inhibitors may be useful in the treatment of one or more cancers selected from brain cancer (gliomas), glioblastomas, Bannayan-Zonana syndrome, Cowden disease, Lhermitte-Duclos disease, breast cancer, inflammatory breast cancer, colorectal cancer, Wilm’s tumor, Ewing’s sarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, ependymoma, medulloblastoma, colon cancer, head and neck cancer, kidney cancer, lung cancer, liver cancer, melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma, ovarian cancer, pancreatic cancer, prostate cancer, sarcoma cancer, osteosarcoma, giant cell tumor of bone, thyroid cancer,

lymphoblastic T-cell leukemia, chronic myelogenous leukemia, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, hairy-cell leukemia, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, acute myelogenous leukemia, chronic neutrophilic leukemia, acute lymphoblastic T-cell leukemia, acute myeloid leukemia, plasmacytoma, immunoblastic large cell leukemia, mantle cell leukemia, multiple myeloma, megakaryoblastic leukemia, acute megakaryocytic leukemia, promyelocytic leukemia, mixed lineage leukaemia, erythroleukemia, malignant lymphoma, Hodgkins lymphoma, non-Hodgkins lymphoma, lymphoblastic T-cell lymphoma, Burkitt’s lymphoma, follicular lymphoma, neuroblastoma, bladder cancer, urothelial cancer, vulval cancer, cervical cancer, endometrial cancer, renal cancer, mesothelioma, esophageal cancer, salivary gland cancer, hepatocellular cancer, gastric cancer, nasopharangeal cancer, buccal cancer, cancer of the mouth, GIST (gastrointestinal stromal tumor) and testicular cancer. In one embodiment the cancer is a leukaemia, for example a leukaemia selected from acute monocytic leukemia, acute myelogenous leukemia, chronic myelogenous leukemia, chronic lymphocytic leukemia,

acute myeloid leukemia and mixed lineage leukaemia (MLL). In another embodiment the cancer is multiple myeloma. In another embodiment the cancer is a lung cancer such as small cell lung cancer (SCLC). In another embodiment the cancer is a neuroblastoma. In another embodiment the cancer is Burkitt’s lymphoma. In another embodiment the cancer is cervical cancer. In another embodiment the cancer is esophageal cancer. In another embodiment the cancer is ovarian cancer. In another embodiment the cancer is breast cancer. In another embodiment the cancer is colarectal cancer. In one embodiment the disease or condition for which a bromodomain inhibitor is indicated is selected from diseases associated with systemic inflammatory response syndrome, such as sepsis, burns, pancreatitis, major trauma, haemorrhage and ischaemia. In this embodiment the

bromodomain inhibitor would be administered at the point of diagnosis to reduce the incidence of: SIRS, the onset of shock, multi-organ dysfunction syndrome, which includes the onset of acute lung injury, ARDS, acute renal, hepatic, cardiac or gastro-intestinal injury and mortality. In another embodiment the bromodomain inhibitor would be administered prior to surgical or other procedures associated with a high risk of sepsis, haemorrhage, extensive tissue damage, SIRS or MODS (multiple organ dysfunction syndrome). In a particular embodiment the disease or condition for which a bromodomain inhibitor is indicated is sepsis, sepsis syndrome, septic shock and endotoxaemia. In another embodiment, the bromodomain inhibitor is indicated for the treatment of acute or chronic pancreatitis. In another embodiment the bromodomain is indicated for the treatment of burns. In one embodiment the disease or condition for which a bromodomain inhibitor is indicated is selected from herpes simplex infections and reactivations, cold sores, herpes zoster infections and reactivations, chickenpox, shingles, human papilloma virus, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), cervical neoplasia, adenovirus infections, including acute respiratory disease, poxvirus infections such as cowpox and smallpox and African swine fever virus. In one particular embodiment a bromodomain inhibitor is indicated for the treatment of Human papilloma virus infections of skin or cervical epithelia. In one embodiment the bromodomain inhibitor is indicated for the treatment of latent HIV infection.

PATENT

WO 2016062737

http://www.google.com/patents/WO2016062737A1?cl=en

Scheme 1

Example 1

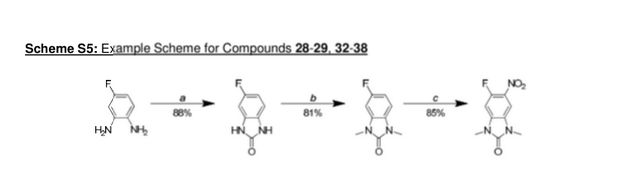

Step 1

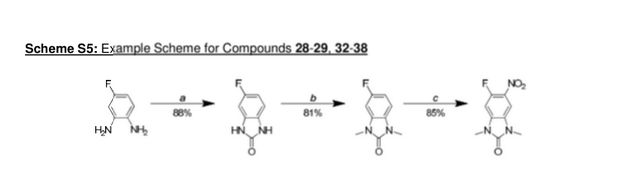

5-fluoro-1 H-benzordlimidazol-2(3H)-one

A stirred solution of 4-fluorobenzene-1 ,2-diamine (15.1 g, 120 mmol) in THF (120 mL) under nitrogen was cooled using an ice-bath and then was treated with di(1 -/-imidazol-1 -yl)methanone (23.4 g, 144 mmol) portion-wise over 15 min. The resulting mixture was slowly warmed to room temperature then was concentrated in vacuo after 2.5 h. The residue was suspended in a mixture of water and DCM (250 mL each) and filtered off. This residue was then washed with water (50 mL) and DCM (50 mL), before being dried at 40 °C under vacuum for 16 h to give the title compound (16.0 g, 105 mmol, 88%) as a brown solid.

LCMS (high pH): Rt 0.57 min; [M-H+]“ = 151.1

δΗ NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) ppm 10.73 (br s, 1 H), 10.61 (br s, 1 H), 6.91-6.84 (m, 1 H), 6.78-6.70 (m, 2H).

Step 2

5-fluoro-1 ,3-dimethyl-1 /-/-benzo[dlimidazol-2(3/-/)-one

A solution of 5-fluoro-1 H-benzo[d]imidazol-2(3H)-one (16.0 g, 105 mmol) in DMF (400 mL) under nitrogen was cooled with an ice-bath, using a mechanical stirrer for agitation. It was then treated over 10 min with sodium hydride (60% w/w in mineral oil, 13.1 g, 327 mmol) and the resulting mixture was stirred at this temperature for 30 min before being treated with iodomethane (26.3 mL, 422 mmol) over 30 min. The resulting mixture was then allowed to warm to room temperature and after 1 h was carefully treated with water (500 mL). The aqueous phase was extracted with EtOAc (3 x 800 mL) and the combined organics were washed with brine (1 L), dried over MgS04 and concentrated in vacuo. Purification of the brown residue by flash chromatography on silica gel (SP4, 1.5 kg column, gradient: 0 to 25% (3: 1 EtOAc/EtOH) in cyclohexane) gave the title compound (15.4 g, 86 mmol, 81 %) as a pink solid.

LCMS (high pH): Rt 0.76 min; [M+H+]+ = 181.1

δΗ NMR (400 MHz, CDCI3) ppm 6.86-6.76 (m, 2H), 6.71 (dd, J = 8.3, 2.3 Hz, 1 H), 3.39 (s, 3H), 3.38 (s, 3H).

Step 3

5-fluoro-1 ,3-dimethyl-6-nitro-1 /-/-benzordlimidazol-2(3/-/)-one

A stirred solution of 5-fluoro-1 ,3-dimethyl-1 H-benzo[d]imidazol-2(3/-/)-one (4.55 g, 25.3 mmol) in acetic anhydride (75 mL) under nitrogen was cooled to -30 °C and then was slowly treated with fuming nitric acid (1 .13 mL, 25.3 mmol) making sure that the temperature was kept below -25°C. The solution turned brown once the first drop of acid was added and a thick brown precipitate formed after the addition was complete. The mixture was allowed to slowly warm up to 0 °C then was carefully treated after 1 h with ice-water (100 mL). EtOAc (15 mL) was then added and the resulting mixture was stirred for 20 min. The precipitate formed was filtered off, washed with water (10 mL) and EtOAc (10 mL), and then was dried under vacuum at 40 °C for 16 h to give the title compound (4.82 g, 21 .4mmol, 85%) as a yellow solid.

LCMS (high pH): Rt 0.76 min; [M+H+]+ not detected

δΗ NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) ppm 7.95 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 1 H, (H-7)), 7.48 (d, J = 1 1.7 Hz, 1 H, (H-4)), 3.38 (s, 3H, (H-10)), 3.37 (s, 3H, (H-12)).

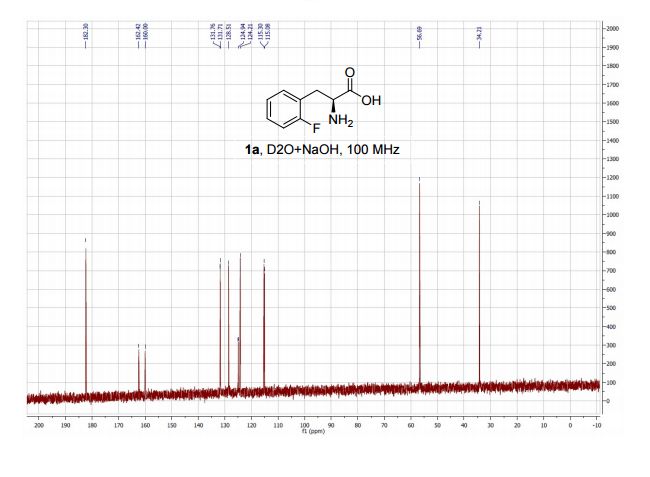

δ0 NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) ppm 154.3 (s, 1 C, (C-2)), 152.3 (d, J = 254.9 Hz, 1 C, (C-5)), 135.5 (d, J = 13.0 Hz, 1 C, (C-9)), 130.1 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1 C, (C-6)), 125.7 (s, 1 C, (C-8)), 104.4 (s, 1 C, (C-7)), 97.5 (d, J = 28.5 Hz, 1 C, (C-4)), 27.7 (s, 1 C, (C-12)), 27.4 (s, 1 C, (C-10)).

Step 4

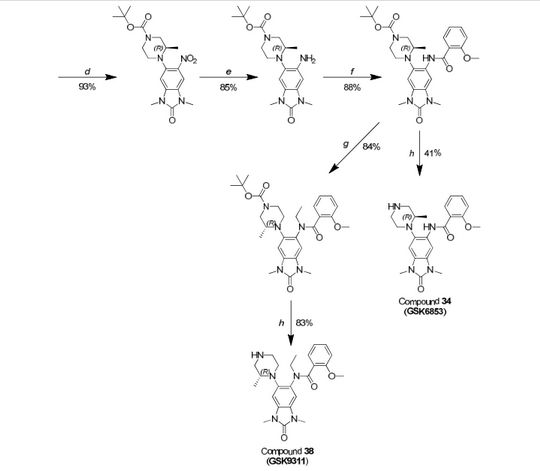

(R)-tert-but \ 4-( 1 ,3-dimethyl-6-nitro-2-oxo-2,3-dihydro-1 H-benzordlimidazol-5-yl)-3-methylpiperazine-1-carboxylate

A stirred suspension of 5-fluoro-1 ,3-dimethyl-6-nitro-1 H-benzo[d]imidazol-2(3/-/)-one (0.924 g, 4.10 mmol), (R)-ie f-butyl 3-methylpiperazine-1 -carboxylate (1.23 g, 6.16 mmol), and DI PEA (1 .43 mL, 8.21 mmol) in DMSO (4 mL) was heated to 120 °C in a Biotage Initiator microwave reactor for 13 h, then to 130 °C for a further 10 h. The reaction mixture was concentrated in vacuo then partitioned between EtOAc and saturated aqueous sodium bicarbonate solution. The aqueous was extracted with EtOAc and the combined organics were dried (Na2S04), filtered, and concentrated in vacuo to give a residue which was purified by silica chromatography (0-100% ethyl acetate in cyclohexane) to give the title compound as an orange/yellow solid (1.542 g, 3.80 mmol, 93%).

LCMS (formate): Rt 1.17 min, [M+H+]+ 406.5.

δΗ NMR (400 MHz, CDCI3) ppm 7.36 (s, 1 H), 6.83 (s, 1 H), 4.04-3.87 (m,1 H), 3.87-3.80 (m, 1 H), 3.43 (s, 6H), 3.35-3.25 (m, 1 H), 3.23-3.08 (m, 2H), 3.00-2.72 (m, 2H), 1.48 (s, 9H), 0.81 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 3H)

Step 5

(RHerf-butyl 4-(6-amino-1 ,3-dimethyl-2-oxo-2,3-dihydro-1 /-/-benzordlimidazol-5-yl)-3-methylpiperazine-1-carboxylate

To (R)-iert-butyl 4-(1 ,3-dimethyl-6-nitro-2-oxo-2,3-dihydro-1 H-benzo[d]imidazol-5-yl)-3-methylpiperazine-1-carboxylate (1 .542 g) in /‘so-propanol (40 mL) was added 5% palladium on carbon (50% paste) (1.50 g) and the mixture was hydrogenated at room temperature and pressure. After 4 h the mixture was filtered, the residue washed with ethanol and DCM, and the filtrate concentrated in vacuo to give a residue which was purified by silica chromatography (50-100% ethyl acetate in cyclohexane) to afford the title compound (1.220 g, 3.25 mmol, 85%) as a cream solid.

LCMS (high pH): Rt 1 .01 min, [M+H+]+ 376.4.

δΗ NMR (400 MHz, CDCI3) ppm 6.69 (s, 1 H), 6.44 (s, 1 H), 4.33-3.87 (m, 4H), 3.36 (s, 3H), 3.35 (s, 3H), 3.20-2.53 (m, 5H), 1.52 (s, 9H), 0.86 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 3H).

Step 6

(flVferf-butyl 4-(6-(2-methoxybenzamidoV 1 ,3-dimethyl-2-oxo-2,3-dihvdro-1 H-benzordlimidazol-5-yl)-3-methylpiperazine-1 -carboxylate

A stirred solution of (R)-iert-butyl 4-(6-amino-1 ,3-dimethyl-2-oxo-2,3-dihydro-1 /-/-benzo[d]imidazol-5-yl)-3-methylpiperazine-1 -carboxylate (0.254 g, 0.675 mmol) and pyridine (0.164 ml_, 2.025 mmol) in DCM (2 mL) at room temperature was treated 2-methoxybenzoyl chloride (0.182 mL, 1.35 mmol). After 1 h at room temperature the reaction mixture was concentrated in vacuo to give a residue which was taken up in DMSO:MeOH (1 :1 ) and purified by HPLC (Method C, high pH) to give the title compound (0.302 g, 0.592 mmol, 88%) as a white solid.

LCMS (high pH): Rt 1 .27 min, [M+H+]+ 510.5.

δΗ NMR (400 MHz, CDCI3) ppm 10.67 (s, 1 H), 8.53 (s, 1 H), 8.24 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.7 Hz, 1 H), 7.54-7.48 (m, 1 H), 7.18-7.12 (m, 1 H), 7.07 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1 H), 6.82 (s, 1 H), 4.27-3.94 (m, 2H), 4.08 (s, 3H), 3.45 (s, 3H), 3.40 (s, 3H), 3.18-2.99 (m, 2H), 2.92-2.70 (m, 3H), 1.50 (s, 9H), 0.87 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 3H).

Step 7

(R)-N-( 1 ,3-dimethyl-6-(2-methylpiperazin-1 -yl)-2-oxo-2,3-dihydro-1 H-benzordlimidazol-5-yl)-2-methoxybenzamide

A stirred solution of (R)-ie f-butyl 4-(6-(2-methoxybenzamido)-1 ,3-dimethyl-2-oxo-2,3-dihydro-1 /-/-benzo[d]imidazol-5-yl)-3-methylpiperazine-1-carboxylate (302 mg, 0.592 mmol) in DCM (4 mL) at room temperature was treated with trifluoroacetic acid (3 ml_). After 15 minutes the mixture was concentrated in vacuo to give a residue which was loaded on a solid-phase cation exchange (SCX) cartridge (5 g), washed with MeOH, and then eluted with methanolic ammonia (2 M). The appropriate fractions were combined and concentrated in vacuo to give a white solid (240 mg). Half of this material was taken up in DMSO:MeOH (1 :1 ) and purified by HPLC (Method B, high pH) to give the title compound (101 mg, 0.245 mmol, 41 %) as a white solid.

LCMS (high pH): Rt = 0.90 min, [M+H+]+ 410.5.

δΗ NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) ppm 10.74 (s, 1 H), 8.39 (s, 1 H), 8.05 (dd, J = 7.7, 1.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.57 (ddd, J = 8.3, 7.2, 2.0 Hz, 1 H), 7.29 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1 H), 7.23 (s, 1 H), 7.17-7.1 1 (m, 1 H), 4.10 (s, 3H), 3.33 (s, 3H), 3.32 (s, 3H), 3.30 (br s, 1 H), 3.07-3.02 (m, 1 H), 3.02-2.99 (m, 1 H), 2.92-2.87 (m, 1 H), 2.80 (td, J = 1 1.3, 2.7 Hz, 1 H), 2.73 (td, J = 1 1 .0, 2.7 Hz, 1 H), 2.68-2.63 (m, 1 H), 2.55 (dd, J = 12.0, 9.8 Hz, 1 H), 0.71 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 3H).

δ0 NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) ppm 162.1 , 156.8, 154.1 , 134.4, 133.2, 131.5, 130.1 , 126.6, 125.7, 121.9, 121.0, 1 12.5, 103.0, 99.4, 56.8, 55.4, 55.3, 53.3, 46.3, 26.8, 26.6, 16.7.

[aD]25 °c = -50.1 (c = 0.3, MeOH).

CLIPS

PAPER

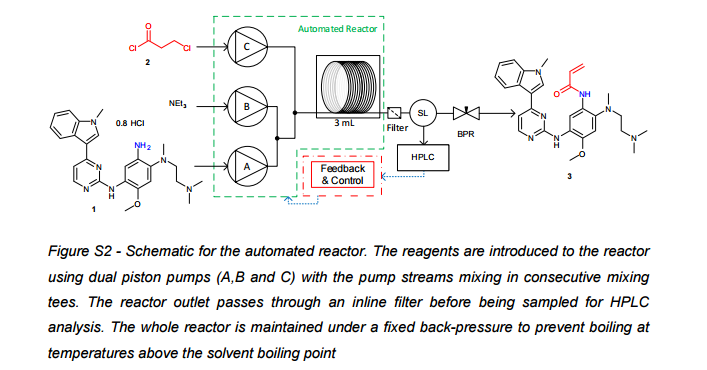

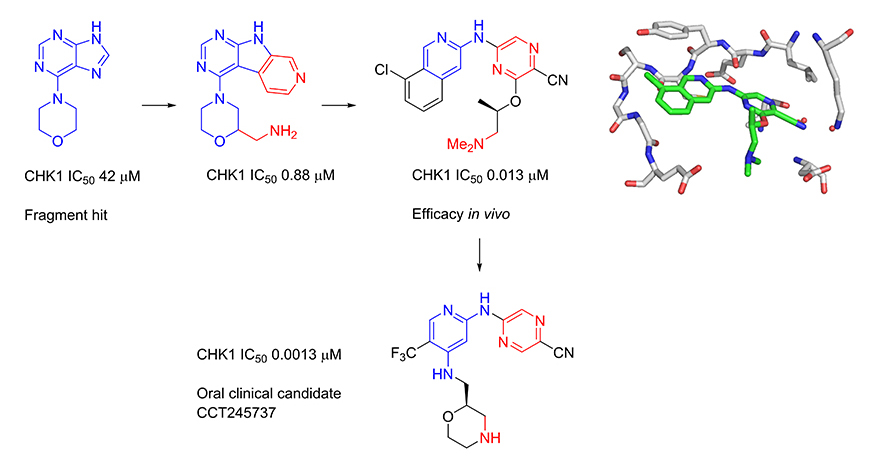

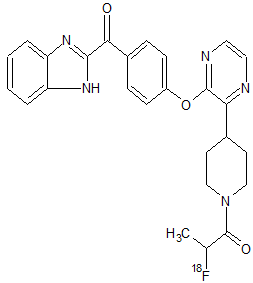

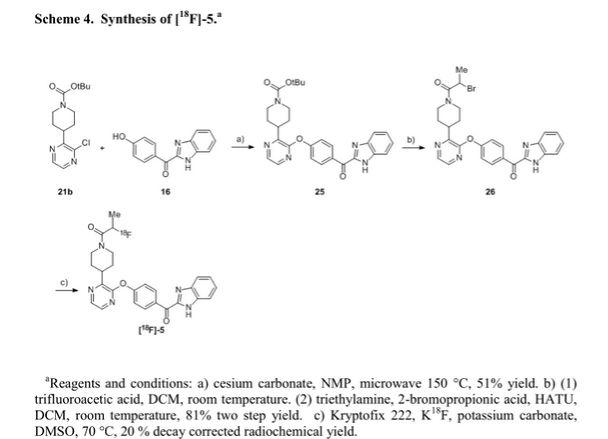

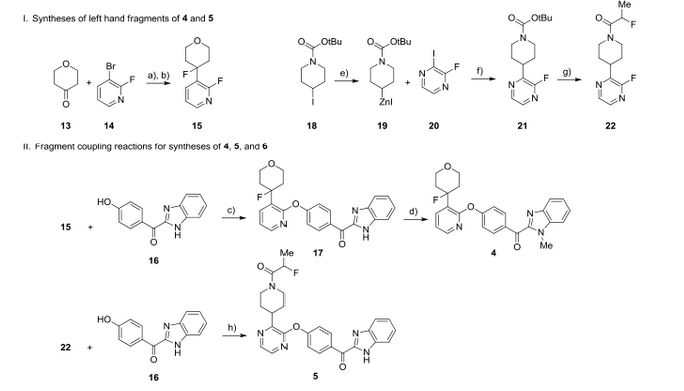

The BRPF (Bromodomain and PHD Finger-containing) protein family are important scaffolding proteins for assembly of MYST histone acetyltransferase complexes. A selective benzimidazolone BRPF1 inhibitor showing micromolar activity in a cellular target engagement assay was recently described. Herein, we report the optimization of this series leading to the identification of a superior BRPF1 inhibitor suitable for in vivo studies.

GSK6853, a Chemical Probe for Inhibition of the BRPF1 Bromodomain

†Epinova Discovery Performance Unit, ‡Quantitative Pharmacology, Experimental Medicine Unit, §Flexible Discovery Unit, and ∥Platform Technology and Science, GlaxoSmithKline, Gunnels Wood Road, Stevenage, Hertfordshire SG1 2NY, U.K.

⊥ Cellzome GmbH, GlaxoSmithKline, Meyerhofstrasse 1, 69117 Heidelberg, Germany

# WestCHEM, Department of Pure and Applied Chemistry, University of Strathclyde, Thomas Graham Building, 295 Cathedral Street, Glasgow G1 1XL, U.K.

ACS Med. Chem. Lett., Article ASAP

DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.6b00092

SEE

Open Access

Open Access

LinkedIn

LinkedIn Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter GooglePlus

GooglePlus