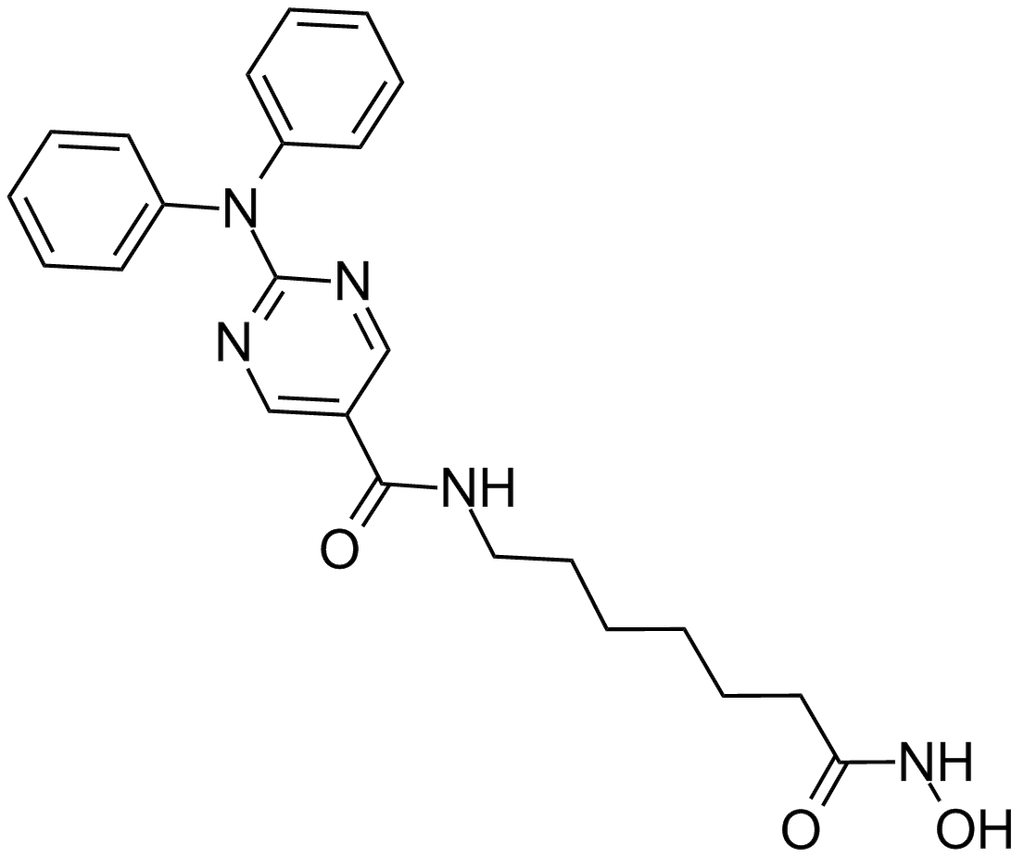

Citarinostat

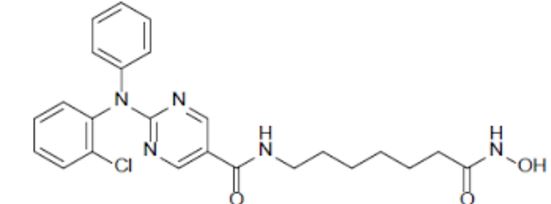

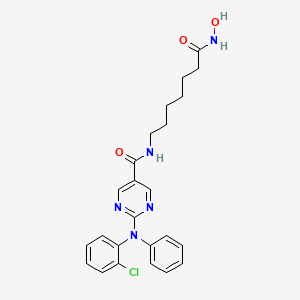

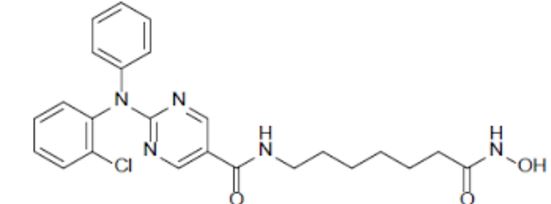

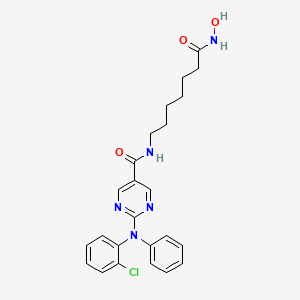

Molecular Formula, C24-H26-Cl-N5-O3, Molecular Weight, 467.9544,

RN: 1316215-12-9

UNII: 441P620G3P

- 2-[(2-Chlorophenyl)phenylamino]-N-[7-(hydroxyamino)-7-oxoheptyl]-5-pyrimidinecarboxamide

ACY-241; HDAC-IN-2

Histone deacetylase-6 inhibitor

Acute myelogenous leukemia; Cancer; Mantle cell lymphoma; Multiple myeloma

- Mechanism of ActionHDAC6 protein inhibitors

Highest Development Phases

- Phase IIMultiple myeloma

- Phase IMalignant melanoma; Non-small cell lung cancer; Solid tumours

Most Recent Events

- 12 Dec 2016Chemical structure information added

- 04 Dec 2016Efficacy and safety data from a phase Ia/Ib clinical trial in Multiple myeloma released by Acetylon

- 03 Jun 2016Phase-II clinical trials in Multiple myeloma in USA (PO)

In December 2016, citarinostat was reported to be in phase 1 clinical development. The drug appears to be first disclosed in WO2011091213, claiming reverse amide derivatives as HDAC-6 inhibitors useful for treating multiple myeloma, Alzheimers disease and psoriasis.

The identification of small organic molecules that affect specific biological functions is an endeavor that impacts both biology and medicine. Such molecules are useful as therapeutic agents and as probes of biological function. Such small molecules have been useful at elucidating signal transduction pathways by acting as chemical protein knockouts, thereby causing a loss of protein function. (Schreiber et al, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1990, 112, 5583; Mitchison, Chem. and Biol., 1994, 15 3) Additionally, due to the interaction of these small molecules with particular biological targets and their ability to affect specific biological function (e.g. gene transcription), they may also serve as candidates for the development of new therapeutics.

One biological target of recent interest is histone deacetylase (HDAC) (see, for example, a discussion of the use of inhibitors of histone deacetylases for the treatment of cancer: Marks et al. Nature Reviews Cancer 2001, 7,194; Johnstone et al. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2002, 287). Post-translational modification of proteins through acetylation and deacetylation of lysine residues plays a critical role in regulating their cellular functions. HDACs are zinc hydrolases that modulate gene expression through deacetylation of the N-acetyl-lysine residues of histone proteins and other transcriptional regulators (Hassig et al Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 1997, 1, 300-308). HDACs participate in cellular pathways that control cell shape and differentiation, and an HDAC inhibitor has been shown effective in treating an otherwise recalcitrant cancer (Warrell et al J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1998, 90, 1621-1625). At this time, eleven human HDACs, which use Zn as a cofactor, have been identified (Taunton et al. Science 1996, 272, 408-411 ; Yang et al. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 28001-28007. Grozinger et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sd. U.S.A. 1999, 96, 4868-4873; Kao et al. Genes Dev. 2000, 14, 55-66. Hu et al J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 15254-15264; Zhou et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Scl U.S.A. 2001, 98, 10572-10577; Venter et al. Science 2001, 291, 1304-1351) these members fall into three classes (class I, II, and IV). An additional seven HDACs h ave been identified which use NAD as a cofactor. To date, no small molecules are known that selectively target any particular class or individual members of this family ((for example ortholog- selective HDAC inhibitors have been reported: (a) Meinke et al. J. Med. Chem. 2000, 14, 4919-4922; (b) Meinke, et al Curr. Med. Chem. 2001, 8, 211-235). There remains a need for preparing structurally diverse HDAC and tubulin deacetylase (TDAC) inhibitors particularly ones that are potent and/or selective inhibitors of particular classes of HDACs or TDACs and individual HDACs and TDACs.

Recently, a cytoplasmic histone deacetylase protein, HDAC6, was identified as necessary for aggresome formation and for survival of cells following ubiquitinated misfolded protein stress. The aggresome is an integral component of survival in cancer cells. The mechanism of HDAC6-mediated aggresome formation is a consequence of the catalytic activity of the carboxy-terminal deacetylase domain, targeting an uncharacterized non-histone target. The present invention also provides small molecule inhibitors of HDAC6. In certain embodiments, these new compounds are potent and selective inhibitors of HDAC6.

The aggresome was first described in 1998, when it was reported that there was an appearance of microtubule-associated perinuclear inclusion bodies in cells over- expressing the pathologic AF508 allele of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance receptor (CFTR). Subsequent reports identified a pathologic appearance of the aggresome with over-expressed presenilin-1 (Johnston JA, et al. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:1883-1898), parkin (Junn E, et al. J Biol Chem. 2002; 277: 47870-47877), peripheral myelin protein PMP22 (Notterpek L, et al. Neurobiol Dis. 1999; 6: 450-460), influenza virus nucleoprotein (Anton LC, et al. J Cell Biol. 1999;146:113-124), a chimera of GFP and the membrane transport protein pi 15 (Garcia- Mata R, et al. J Cell Biol. 1999; 146: 1239-1254) and notably amyloidogenic light chains (Dul JL, et al. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:705-716). Model systems have been established to study ubiquitinated (AF508 CFTR) (Johnston JA, et al. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:1883-1898) and non-ubiquitinated (GFP -250) (Garcia-Mata R, et al. J Cell Biol. 1999;146:1239-1254) protein aggregate transport to the aggresome. Secretory, mutated, and wild-type proteins may assume unstable kinetic intermediates resulting in stable aggregates incapable of degradation through the narrow channel of the 26S proteasome. These complexes undergo active, retrograde transport by dynein to the pericentriolar aggresome, mediated in part by a cytoplasmic histone deacetylase, HDAC6 (Kawaguchi Y, et al. Cell. 2003;1 15:727-738).

Histone deacetylases are a family of at least 11 zinc -binding hydrolases, which

catalyze the deacetylation of lysine residues on histone proteins. HDAC inhibition results in hyperacetylation of chromatin, alterations in transcription, growth arrest, and apoptosis in cancer cell lines. Early phase clinical trials with available nonselective HDAC inhibitors demonstrate responses in hematologic malignancies including multiple myeloma, although with significant toxicity. Of note, in vitro synergy of conventional chemotherapy agents (such as melphalan) with bortezomib has been reported in myeloma cell lines, though dual proteasome-aggresome inhibition was not proposed. Until recently selective HDAC inhibitors have not been realized.

HDAC6 is required for aggresome formation with ubiquitinated protein stress and is essential for cellular viability in this context. HDAC6 is believed to bind ubiquitinated proteins through a zinc finger domain and interacts with the dynein motor complex through another discrete binding motif. HDAC6 possesses two catalytic deacetylase domains. It is not presently known whether the amino-terminal histone deacetylase or the carboxy-terminal tubulin deacetylase (TDAC) domain mediates aggresome formation.

Aberrant protein catabolism is a hallmark of cancer, and is implicated in the stabilization of oncogenic proteins and the degradation of tumor suppressors (Adams J. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:349-360). Tumor necrosis factor alpha induced activation of nuclear factor kappa B (NFKB) is a relevant example, mediated by NFKB inhibitor beta (1KB) proteolytic degradation in malignant plasma cells. The inhibition of 1KB catabolism by proteasome inhibitors explains, in part, the apoptotic growth arrest of treated myeloma cells (Hideshima T, et al. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3071-3076). Multiple myeloma is an ideal system for studying the mechanisms of protein degradation in cancer. Since William Russell in 1890, cytoplasmic inclusions have been regarded as a defining histological feature of malignant plasma cells. Though the precise composition of Russell bodies is not known, they are regarded as ER-derived vesicles containing aggregates of monotypic immunoglobulins

(Kopito RR, Sitia R. EMBO Rep. 2000; 1 :225-231) and stain positive for ubiquitin (Manetto V, et al. Am J Pathol. 1989;134:505-513). Russell bodies have been described with CFTR over-expression in yeast (Sullivan ML, et al. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2003;51 :545-548), thus raising the suspicion that these structures may be linked to overwhelmed protein catabolism, and potentially the aggresome. The role of the aggresome in cancer remains undefined.

Aberrant histone deacetylase activity has also been linked to various neurological and neurodegenerative disorders, including stroke, Huntington’s disease, Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Alzheimer’s disease. HDAC inhibition may induce the expression of antimitotic and anti-apoptotic genes, such as p21 and HSP-70, which facilitate survival. HDAC inhibitors can act on other neural cell types in the central nervous system, such as reactive astrocytes and microglia, to reduce inflammation and secondary damage during neuronal injury or disease. HDAC inhibition is a promising therapeutic approach for the treatment of a range of central nervous system disorders (Langley B et al., 2005, Current Drug Targets— CNS & Neurological Disorders, 4: 41-50).

Histone deacetylase is known to play an essential role in the transcriptional machinery for regulating gene expression, induce histone hyperacetylation and to affect the gene expression. Therefore, it is useful as a therapeutic or prophylactic agent for diseases caused by abnormal gene expression such as inflammatory disorders, diabetes, diabetic

complications, homozygous thalassemia, fibrosis, cirrhosis, acute promyelocytic leukaemia (APL), organ transplant rejections, autoimmune diseases, protozoal infections, tumors, etc.

Thus, there remains a need for the development of novel inhibitors of histone deacetylases and tubulin histone deacetylases. In particular, inhibitors that are more potent and/or more specific for their particular target than known HDAC and TDAC inhibitors. HDAC inhibitors specific for a certain class or member of the HDAC family would be particularly useful both in the treatment of proliferative diseases and protein deposition disorders and in the study of HDACs, particularly HDAC6. Inhibitors that are specific for HDAC versus TDAC and vice versa are also useful in treating disease and probing biological pathways. The present invention provides novel compounds, pharmaceutical compositions thereof, and methods of using these compounds to treat disorders related to HDAC6 including cancers, inflammatory, autoimmune, neurological and neurodegenerative disorders

Rocilinostat (ACY-1215)

PATENT

WO2011091213

https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=WO2011091213

Patent

US20160355486

WO 2013013113

WO 2015061684

WO 2015054474

US 20150099744

PATENT

CITARINOSTAT BY ACTYLON

WO-2016200919

Crystalline forms of a histone deacetylase inhibitor

Novel crystalline polymorphic forms of citarinostat, useful for treating cancer, eg multiple myeloma, mantle cell lymphoma or acute myelogenous leukemia. Also claims a method for preparing the crystalline form of citarinostat. Acetylon is developing citarinostat, a next generation selective inhibitor of HDAC6, for treating multiple myeloma and solid tumors, including melanoma.

Provided herein are crystalline forms of 2-((2-chlorophenyl)(phenyl)amino)-N-(7-(hydroxyamino)-7-oxoheptyl)pyrimidine-5-carboxamide (CAS No. 1316215-12-9), shown as Compound (I) (and referred to herein as “Compound (I)”):

Compound (I) is disclosed in International Patent Application No.

PCT/US2011/021982 and U.S. Patent No. 8,609,678, the entire contents of which are incorporated herein by reference.

Accordingly, provided herein are crystalline forms of 2-((2-chlorophenyl)(phenyl)amino)-N-(7-(hydroxyamino)-7-oxoheptyl)pyrimidine-5-carboxamide. In particular, provided herein are the following crystalline forms of Compound (I): Form I, Form II, Form III, Form IV, Form V, Form VI, Form VII, Form VIII, and Form IX. Each of these forms have been characterized by XRPD analysis. In an embodiment, the crystalline form of 2-((2-chlorophenyl)(phenyl)amino)-N-(7-(hydroxyamino)-7-oxoheptyl)pyrimidine-5-carboxamide can be a hydrate or solvate (e.g., dichloromethane or methanol).

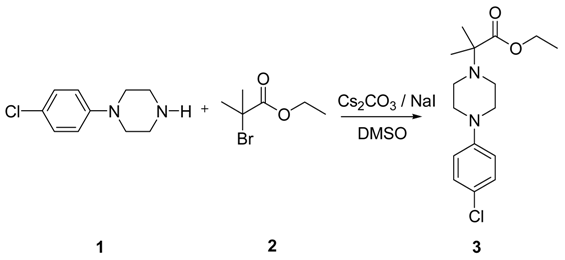

EXAMPLES

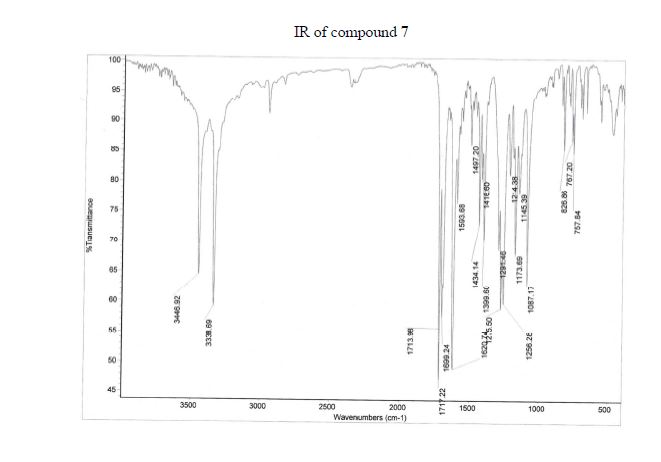

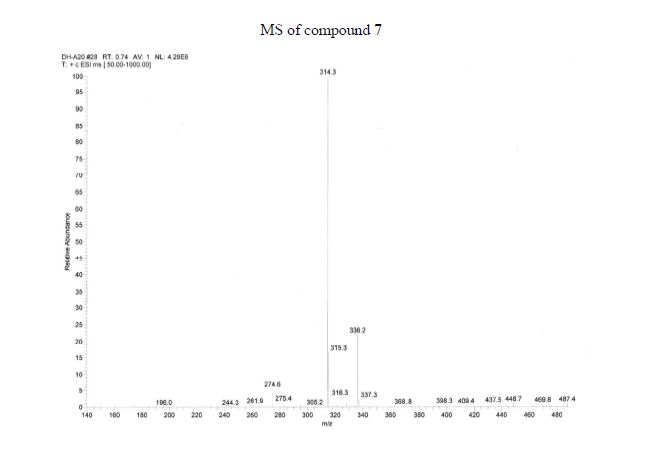

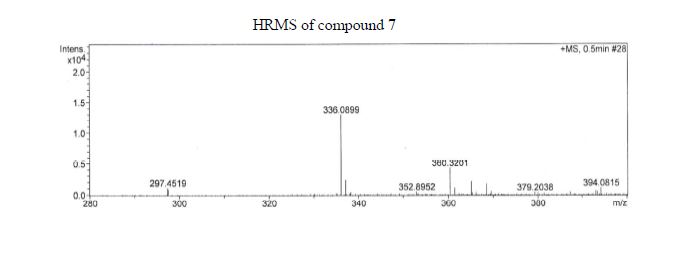

Example 1: Synthesis of 2-((2-chlorophenyl)(phenyl)amino)-N-(7-(hydroxyamino)-7- oxoheptyl)pyrimidine-5-carboxamide (Compound (I))

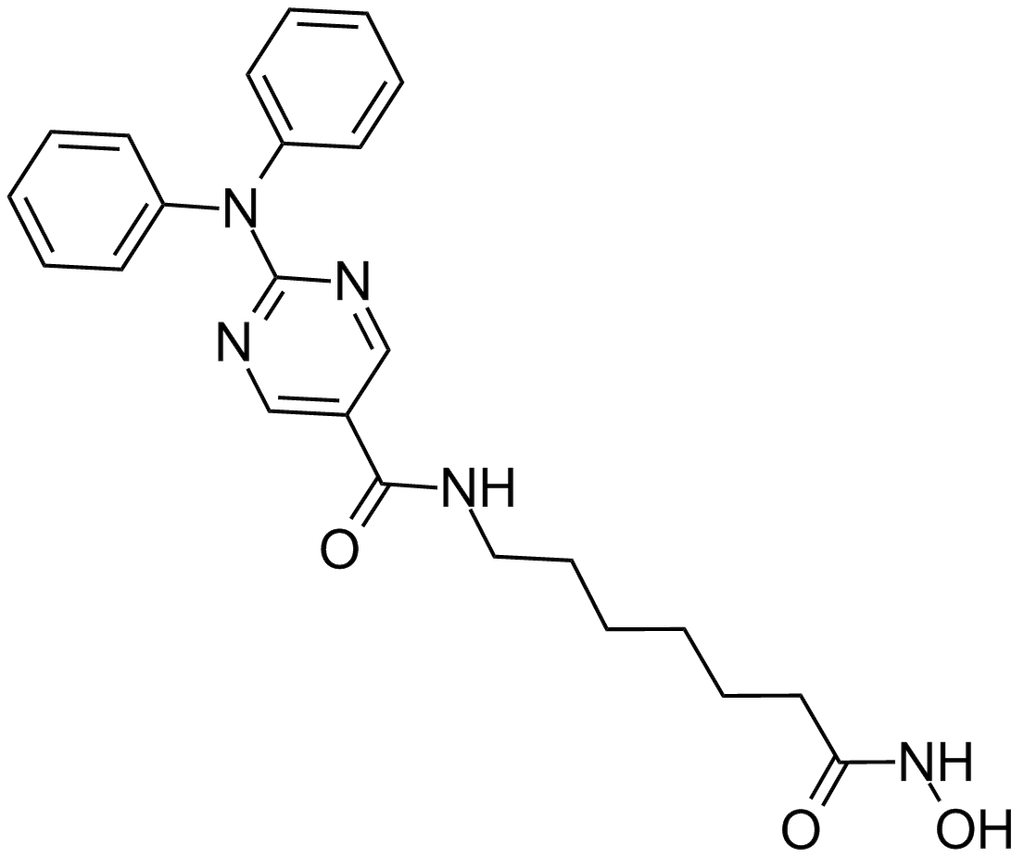

I. Synthesis of 2-(diphenylamino)-N-(7-(hydroxyamino)-7-oxoheptyl)pyrimidine-5-carboxamide:

Synthesis of Intermediate 2: A mixture of aniline (3.7 g, 40 mmol), compound 1 (7.5 g, 40 mmol), and K2C03 (11 g, 80 mmol) in DMF (100 ml) was degassed and stirred at 120 °C under N2 overnight. The reaction mixture was cooled to r.t. and diluted with EtOAc (200 ml), then washed with saturated brine (200 ml χ 3). The organic layers were separated and dried over Na2S04, evaporated to dryness and purified by silica gel chromatography (petroleum ethers/EtOAc = 10/1) to give the desired product as a white solid (6.2 g, 64 %).

Synthesis of Intermediate 3: A mixture of compound 2 (6.2 g, 25 mmol), iodobenzene (6.12 g, 30 mmol), Cul (955 mg, 5.0 mmol), Cs2C03 (16.3 g, 50 mmol) in TEOS (200 ml) was degassed and purged with nitrogen. The resulting mixture was stirred at 140 °C for 14 hrs. After cooling to r.t., the residue was diluted with EtOAc (200 ml). 95% EtOH (200 ml) and H4F-H20 on silica gel [50g, pre-prepared by the addition of H4F (lOOg) in water (1500 ml) to silica gel (500g, 100-200 mesh)] was added, and the resulting mixture was kept at r.t. for 2 hrs. The solidified materials were filtered and washed with EtOAc. The filtrate was evaporated to dryness and the residue was purified by silica gel chromatography (petroleum ethers/EtOAc = 10/1) to give a yellow solid (3 g, 38%).

Synthesis of Intermediate 4: 2N NaOH (200 ml) was added to a solution of compound 3 (3.0 g, 9.4 mmol) in EtOH (200 ml). The mixture was stirred at 60 °C for 30min. After evaporation of the solvent, the solution was neutralized with 2N HCl to give a white precipitate. The suspension was extracted with EtOAc (2 χ 200 ml), and the organic layers were separated, washed with water (2 χ 100 ml), brine (2 χ 100 ml), and dried over Na2S04. Removal of the solvent gave a brown solid (2.5 g, 92 %).

Synthesis of Intermediate 6: A mixture of compound 4 (2.5 g, 8.58 mmol), compound 5 (2.52 g, 12.87 mmol), HATU (3.91 g, 10.30 mmol), and DIPEA (4.43 g, 34.32 mmol) was stirred at r.t. overnight. After the reaction mixture was filtered, the filtrate was evaporated to dryness and the residue was purified by silica gel chromatography (petroleum ethers/EtOAc = 2/1) to give a brown solid (2 g, 54 %).

Synthesis of 2-(diphenylamino)-N-(7-(hydroxyamino)-7-oxoheptyl)pyrimidine-5-carboxamide: A mixture of the compound 6 (2.0 g, 4.6 mmol), sodium hydroxide (2N, 20 mL) in MeOH (50 ml) and DCM (25 ml) was stirred at 0 °C for 10 min. Hydroxylamine (50%) (10 ml) was cooled to 0 °C and added to the mixture. The resulting mixture was stirred at r.t. for 20 min. After removal of the solvent, the mixture was neutralized with 1M HCl to give a white precipitate. The crude product was filtered and purified by pre-HPLC to give a white solid (950 mg, 48%).

II. Synthetic Route 1 : 2-((2-chlorophenyl)(phenyl)amino)-N-(7-(hydroxyamino)-7-oxoheptvDpyrimidine-5-carboxamide

Synthesis of Intermediate 2: A mixture of aniline (3.7 g, 40 mmol), ethyl 2-chloropyrimidine-5-carboxylate 1 (7.5 g, 40 mmol), K2C03 (11 g, 80 mmol) in DMF (100 ml) was degassed and stirred at 120 °C under N2 overnight. The reaction mixture was cooled to rt and diluted with EtOAc (200 ml), then washed with saturated brine (200 ml x 3). The organic layer was separated and dried over Na2S04, evaporated to dryness and purified by silica gel

chromatography (petroleum ethers/EtOAc = 10/1) to give the desired product as a white solid (6.2 g, 64 %).

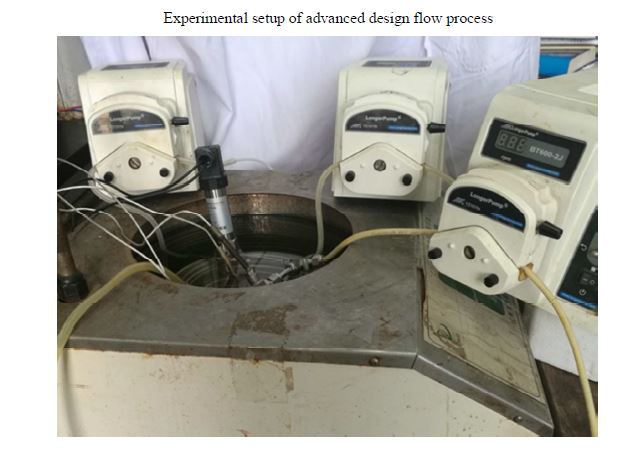

Synthesis of Intermediate 3: A mixture of compound 2 (69.2 g, 1 equiv.), l-chloro-2-iodobenzene (135.7 g, 2 equiv.), Li2C03 (42.04 g, 2 equiv.), K2C03 (39.32 g, 1 equiv.), Cu (1 equiv. 45 μπι) in DMSO (690 ml) was degassed and purged with nitrogen. The resulting mixture was stirred at 140 °C for 36 hours. Work-up of the reaction gave compound 3 at 93 % yield.

Synthesis of Intermediate 4: 2N NaOH (200 ml) was added to a solution of the compound 3 (3.0 g, 9.4 mmol) in EtOH (200 ml). The mixture was stirred at 60 °C for 30min. After evaporation of the solvent, the solution was neutralized with 2N HC1 to give a white precipitate. The suspension was extracted with EtOAc (2 x 200 ml), and the organic layer was separated, washed with water (2 x 100 ml), brine (2 x 100 ml), and dried over Na2S04. Removal of solvent gave a brown solid (2.5 g, 92 %).

Synthesis of Intermediate 5: A procedure analogous to the Synthesis of Intermediate 6 in Part I of this Example was used.

Synthesis of 2-((2-chlorophenyl)(phenyl)amino)-N-(7-(hydroxyamino)-7-oxoheptyl)pyrimidine-5-carboxamide: A procedure analogous to the Synthesis of 2-(diphenylamino)-N-(7-(hydroxyamino)-7-oxoheptyl)pyrimidine-5-carboxamide in Part I of this Example was used.

III. Synthetic Route 2: 2-((2-chlorophenyl)(phenyl)amino)-N-(7-(hydroxyamino)-7-oxoheptyl)pyrimidine-5-carboxamide

(I)

Step (1): Synthesis of Compound 11: Ethyl 2-chloropyrimidine-5-carboxylate (7.0 Kgs), ethanol (60 Kgs), 2-Chloroaniline (9.5 Kgs, 2 eq) and acetic acid (3.7 Kgs, 1.6 eq) were charged to a reactor under inert atmosphere. The mixture was heated to reflux. After at least 5 hours the reaction was sampled for HPLC analysis (method TM-113.1016). When analysis indicated reaction completion, the mixture was cooled to 70 ± 5 °C and N,N-Diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA) was added. The reaction was then cooled to 20 ± 5°C and the mixture was stirred for an additional 2-6 hours. The resulting precipitate is filtered and washed with ethanol (2 x 6 Kgs) and heptane (24 Kgs). The cake is dried under reduced pressure at 50 ± 5 °C to a constant weight to produce 8.4 Kgs compound 11 (81% yield and 99.9% purity.

Step (2): Synthesis of Compound 3: Copper powder (0.68 Kgs, 1 eq, <75 micron), potassium carbonate (4.3 Kgs, 1.7 eq), and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, 12.3 Kgs) were added to a reactor (vessel A). The resulting solution was heated to 120 ± 5°C. In a separate reactor (vessel B), a solution of compound 11 (2.9 Kgs) and iodobenzene (4.3 Kgs, 2 eq) in DMSO (5.6 Kgs) was heated at 40 ± 5°C. The mixture was then transferred to vessel A over 2-3 hours. The reaction mixture was heated at 120 ± 5°C for 8-24 hours, until HPLC analysis (method TM-113.942) determined that < 1% compound 11 was remaining.

Step (3): Synthesis of Compound 4: The mixture of Step (2) was cooled to 90-100 °C and purified water (59 Kgs) was added. The reaction mixture was stirred at 90-100 °C for 2-8 hours until HPLC showed that <1% compound 3 was remaining. The reactor was cooled to 25 °C. The reaction mixture was filtered through Celite, then a 0.2 micron filter, and the filtrate was collected. The filtrate was extracted with methyl t-butyl ether twice (2 x 12.8 Kgs). The aqueous layer was cooled to 0-5 °C, then acidified with 6N hydrochloric acid (HC1) to pH 2-3 while keeping the temperature < 25°C. The reaction was then cooled to 5-15 °C. The precipitate was filtered and washed with cold water. The cake was dried at 45-55 °C under reduced pressure to constant weight to obtain 2.2 kg (65% yield) compound 4 in 90.3% AUC purity.

Step (4): Synthesis of Compound 5: Dichloromethane (40.3 Kgs), DMF (33g, 0.04 eq) and compound 4 (2.3 Kg) were charged to a reaction flask. The solution was filtered through a 0.2 μπι filter and was returned to the flask. Oxalyl chloride (0.9 Kgs, 1 eq) was added via addition funnel over 30-120 minutes at < 30 °C. The batch was then stirred at < 30°C until reaction completion (compound 4 <3 %) was confirmed by HPLC (method TM-113.946. Next, the dichloromethane solution was concentrated and residual oxalyl chloride was removed under reduced pressure at < 40 °C. When HPLC analysis indicated that < 0.10% oxalyl chloride was remaining, the concentrate was dissolved in fresh dichloromethane (24 Kgs) and transferred back to the reaction vessel (Vessel A).

A second vessel (Vessel B) was charged with Methyl 7-aminoheptanoate

hydrochloride (Compound Al, 1.5 Kgs, 1.09 eq), DIPEA (2.5 Kgs, 2.7 eq), 4

(Dimethylamino)pyridine (DMAP, 42g, 0.05 eq), and DCM (47.6 Kgs). The mixture was cooled to 0-10 °C and the acid chloride solution in Vessel A was transferred to Vessel B while maintaining the temperature at 5 °C to 10 °C. The reaction is stirred at 5-10 °C for 3 to 24 hours at which point HPLC analysis indicated reaction completion (method TM-113.946, compound 4 <5%). The mixture was then extracted with a 1M HC1 solution (20 Kgs), purified water (20 Kgs), 7% sodium bicarbonate (20 Kgs), purified water (20 Kgs), and 25% sodium chloride solution (20 Kgs). The dichloromethane was then vacuumdistilled at < 40 °C and chased repeatedly with isopropyl alcohol. When analysis indicated that <1 mol% DCM was remaining, the mixture was gradually cooled to 0-5 °C and was stirred at 0-5 °C for an at least 2 hours. The resulting precipitate was collected by filtration and washed with cold isopropyl alcohol (6.4 Kgs). The cake was sucked dry on the filter for 4-24 hours, then was further dried at 45-55 °C under reduced pressure to constant weight. 2.2 Kgs (77% yield) was isolated in 95.9% AUC purity method and 99.9 wt %.

Step (5): Synthesis of Compound (I): Hydroxylamine hydrochloride (3.3 Kgs, 10 eq) and methanol (9.6 Kgs) were charged to a reactor. The resulting solution was cooled to 0-5 °C and 25% sodium methoxide (11.2 Kgs, 11 eq) was charged slowly, maintaining the temperature at 0-10 °C. Once the addition was complete, the reaction was mixed at 20 °C for 1-3 hours and filtered, and the filter cake was washed with methanol (2 x 2.1 Kgs). The filtrate (hydroxylamine free base) was returned to the reactor and cooled to 0±5°C.

Compound 5 (2.2 Kgs) was added. The reaction was stirred until the reaction was complete (method TM-113.964, compound 5 < 2%). The mixture was filtered and water (28 Kgs) and ethyl acetate (8.9 Kgs) were added to the filtrate. The pH was adjusted to 8 – 9 using 6N HC1 then stirred for up to 3 hours before filtering. The filter cake was washed with cold water (25.7 Kgs), then dried under reduced pressure to constant weight. The crude solid compound (I) was determined to be Form IV/ Pattern D.

The crude solid (1.87 Kgs) was suspended in isopropyl alcohol (IP A, 27.1 Kg). The slurry was heated to 75±5 °C to dissolve the solids. The solution was seeded with crystals of Compound (I) (Form I/Pattern A), and was allowed to cool to ambient temperature. The resulting precipitate was stirred for 1-2 hours before filtering. The filter cake was rinsed with IPA (2 x 9.5 Kgs), then dried at 45-55°C to constant weight under reduced pressure to result in 1.86 kg crystalline white solid Compound (I) (Form I/Pattern A) in 85% yield and 99.5% purity (AUC%, HPLC method TM-113.941).

HPLC Method 113.941

Column Zorbax Eclipse XDB-C18, 4.6 mm x 150 mm, 3.5 μπι

Column Temperature 40°C

UV Detection Wavelength Bandwidth 4 nm, Reference off, 272 nm

Flow rate 1.0 mL/min

Injection Volume 10 μΐ. with needle wash

Mobile Phase A 0.05% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in purified water

Mobile Phase B 0.04% TFA in acetonitrile

Data Collection 40.0 min

Run Time 46.0 min

Gradient Time (min) Mobile Phase A Mobile Phase B

0.0 98% 2%

36.0 0% 100%

40.0 0% 100%

40.1 98% 2%

46.0 98% 2%

Example 2: Summary of Results and Analytical Techniques

Table 1. Summary of the Isolated Crystalline Forms of Compound (I)

| Patent ID |

Patent Title |

Submitted Date |

Granted Date |

| US2016030458 |

TREATMENT OF LEUKEMIA WITH HISTONE DEACETYLASE INHIBITORS |

2015-07-06 |

2016-02-04 |

| US2015176076 |

HISTONE DEACETYLASE 6 (HDAC6) BIOMARKERS IN MULTIPLE MYELOMA |

2014-12-19 |

2015-06-25 |

| US2015150871 |

COMBINATIONS OF HISTONE DEACETYLASE INHIBITORS AND IMMUNOMODULATORY DRUGS |

2014-12-03 |

2015-06-04 |

| US2015119413 |

TREATMENT OF POLYCYSTIC DISEASES WITH AN HDAC6 INHIBITOR |

2014-10-24 |

2015-04-30 |

| US2015105358 |

COMBINATIONS OF HISTONE DEACETYLASE INHIBITORS AND IMMUNOMODULATORY DRUGS |

2014-10-07 |

2015-04-16 |

| US2015105383 |

HDAC Inhibitors, Alone Or In Combination With PI3K Inhibitors, For Treating Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma |

2014-10-08 |

2015-04-16 |

| US2015105384 |

PYRIMIDINE HYDROXY AMIDE COMPOUNDS AS HISTONE DEACETYLASE INHIBITORS |

2014-10-09 |

2015-04-16 |

| US2015105409 |

HDAC INHIBITORS, ALONE OR IN COMBINATION WITH BTK INHIBITORS, FOR TREATING NONHODGKIN’S LYMPHOMA |

2014-10-07 |

2015-04-16 |

| US2015099744 |

COMBINATIONS OF HISTONE DEACETYLASE INHIBITORS AND EITHER HER2 INHIBITORS OR PI3K INHIBITORS |

2014-10-06 |

2015-04-09 |

| US2015045380 |

REVERSE AMIDE COMPOUNDS AS PROTEIN DEACETYLASE INHIBITORS AND METHODS OF USE THEREOF |

2014-10-22 |

2015-02-12 |

Acetylon Crafts New Buyout Deal With Celgene, Spins Out Startup Regenacy

In the deal, Summit, NJ-based Celgene (NASDAQ: CELG) will get partial rights to two drug candidates developed by Acetylon: citarinostat (also known as ACY-241), and ricolinostat (ACY-1215). Specifically, Celgene will get worldwide rights to develop both drugs for cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and autoimmune diseases, but nothing else.

Regenacy meanwhile, will also have partial rights to these two drugs, but only for other disease types, such as nerve pain. It also gets access to other preclinical drugs Acetylon has been developing for blood diseases like sickle cell disease and beta-thalassemia.

[Updated w/comments from CEO] Acetylon CEO Walter Ogier—who will be the president and CEO of Regenacy—said via e-mail that Celgene was only interested in the parts of Acetylon that fit with its current portfolio. Acetylon’s shareholders and executives, meanwhile, wanted to push the rest of the company’s experimental products forward. So the two companies let the original deal expire and came up with the new transaction.

“The remaining assets are exciting enough to create a new company to advance,” Ogier said.

Other “key members” of Acetylon’s executive team will switch over to the new company as well, according to the announcement. Ogier said Regenacy has acquired Acetylon’s remaining cash in the deal—he didn’t say how much—to get itself started.

Both citarinostat and ricolinostat interfere with what are known as histone deacetylases (HDACs), enzymes that help regulate gene expression and are implicated in a number of cancers. HDACs are a well-known molecular target, but Acetylon’s drugs are part of a newer breed of HDAC-blocking agents meant to be more precise, and thus less toxic, than their predecessors. Acetylon’s lead drug ricolinostat, for instance, is meant to block only the specific enzyme HDAC6. Citarinostat is a pill version of ricolinostat,

With Celgene’s help, Acetylon has been developing these drugs as potential treatments for breast cancer and the blood cancer multiple myeloma. It has been testing the drug in combination with Celgene’s own experimental drugs, like the myeloma drug pomalidomide (Pomalyst) and the breast cancer drug nab-paclitaxel (Abraxane).

[Updated w/CEO comments] Citarinostat, for instance, is being tested as a multiple myeloma treatment in a Phase 1b trial in combination with pomalidamide and dexamethasome in multiple myeloma. Acetylon and Celgene just reported early data at the American Society of Hematology’s annual meeting. Ricolinostat is in a mid-stage study in multiple myeloma as well as several investigator-sponsored studies in lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and ovarian and breast cancer, according to Ogier.

Regenacy will take ricolinostat into a Phase 2 trial in peripheral neuropathy next year, he says.

The two companies aren’t disclosing the terms of the deal. Co-founder and chairman Marc Cohen said in a statement that the deal is a “favorable outcome” for Acetylon’s shareholders—an unusual mix of private financiers, non-profits, public companies, and federal grant sources including Celgene itself, Kraft Group (the holding company founded by New England Patriots owner Robert Kraft), Cohen, and the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society. (All of those shareholders aside from Celgene will be the owners of Regenacy.)

But it’s a different outcome than Acetylon and Celgene anticipated when they signed a broad deal in 2013. At that time, Celgene paid Acetylon $100 million for the option to buy it outright for at least an additional $500 million (the actual price was to be tied to an independent valuation). The deal included another $1.1 billion in “bio-bucks,” future payments tied to clinical progress that may or may not materialize. All told, that meant the Celgene deal could have been worth $1.7 billion to Acetylon and its shareholders. Acetylon raised $55 million from shareholders before it struck that deal with Celgene.

Celgene extended its partnership with Acetylon in the summer of 2015, but that included a contingency that the relationship would end in May 2016 if it didn’t buy Acetylon. A regulatory filing in July showed that’s exactly what happened: the collaboration between the two companies ended this year, and that Celgene was no longer on the hook for any future payments related to 2013 deal.

Though that deal is now history, Acetylon shareholders were at least able to generate some type of return—and take another shot on some of the same assets. Ogier said these shareholders have “ample capacity” to make further investments in Regenacy, though the company will try to find new partners to help move its programs forward as well.

“We are excited to continue Acetylon’s legacy through the receipt of rights to many of Acetylon’s most promising compounds and the continued advancement of these clinical and preclinical programs in disease indications outside of Celgene’s areas of strategic focus, where we believe patients may especially benefit from selective HDAC inhibition,” he said in a statement.

REFERENCES

http://www.acetylon.com/docs/ACE-MM-200_Poster_Final%20Draft.pdf

References:

[1]. Quayle SN, Almeciga-Pinto I, Tamang D, et al. Selective HDAC inhibition by ricolinostat (ACY-1215) or ACY-241 synergizes with IMiD® immunomodulatory drugs in Multiple Myeloma (MM) and Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL) cells. In: Proceedings of the 106th Annual Meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research, 2015, Philadelphia, PA. Philadelphia (PA): AACR; Cancer Res 2015;75(15 Suppl):Abstract nr 5380.

[2]. Huang P, Almeciga-Pinto I, Jordan M, et al. Selective HDAC inhibition by ACY-241 enhances the activity of paclitaxel in solid tumor models. In: Proceedings of the 2015 AACR-NCI-EORTC International Conference on Molecular Targets and Cancer Therapeutics; 2015 Nov 5-9; Boston, Massachusetts. Philadelphia (PA): AACR

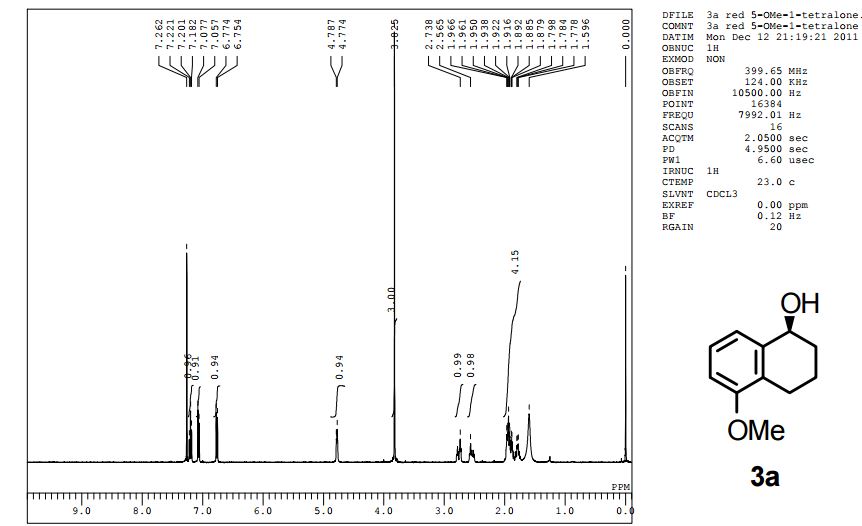

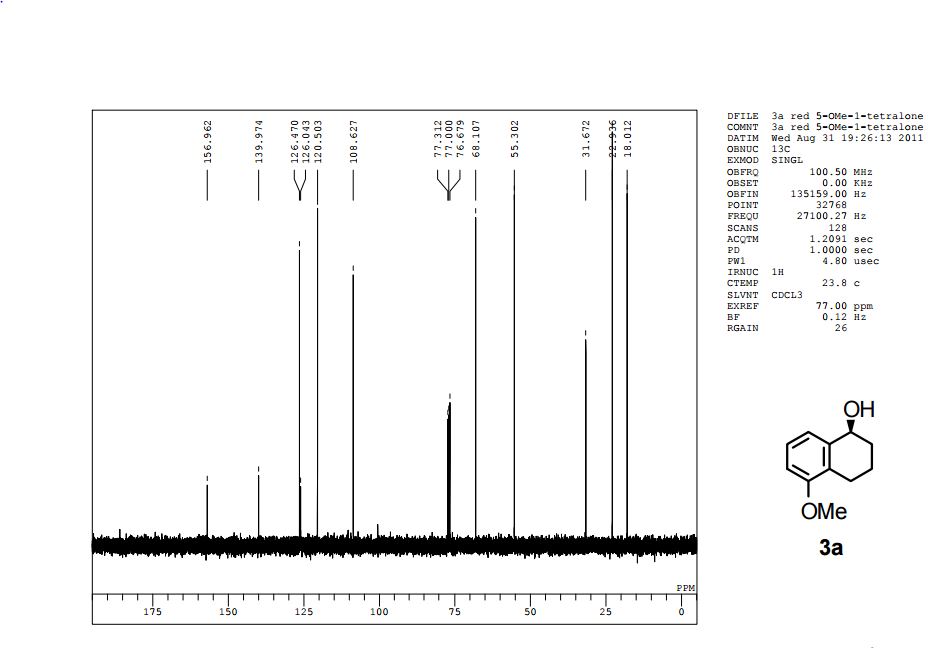

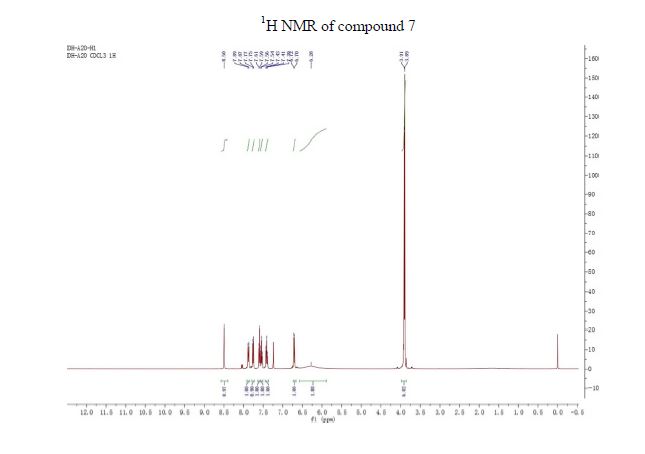

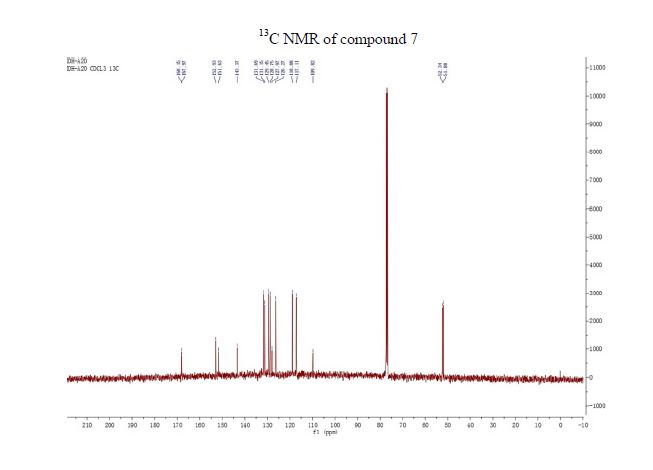

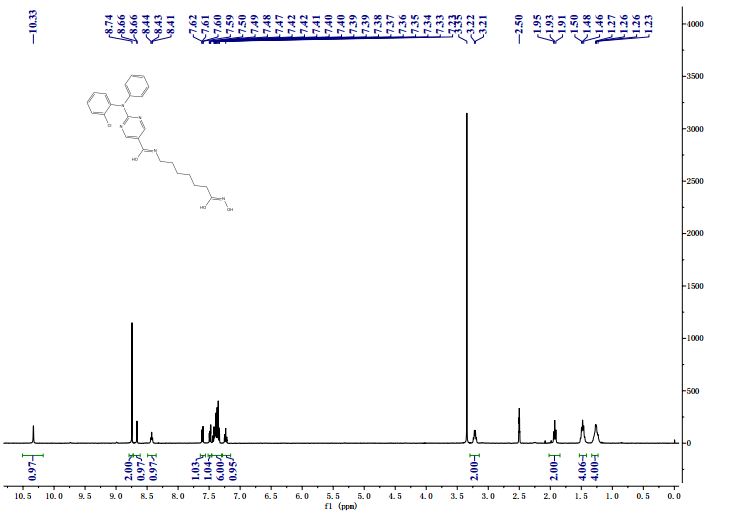

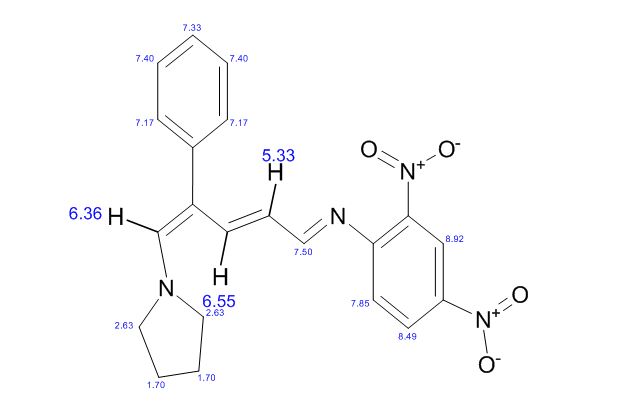

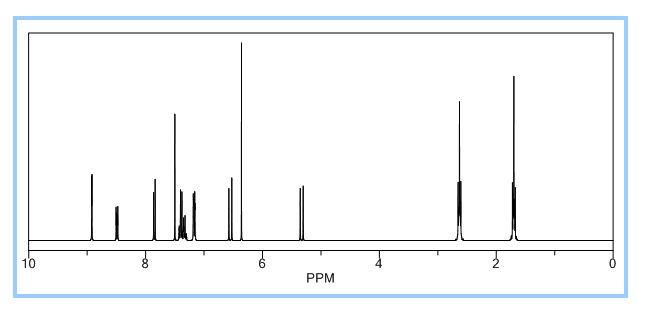

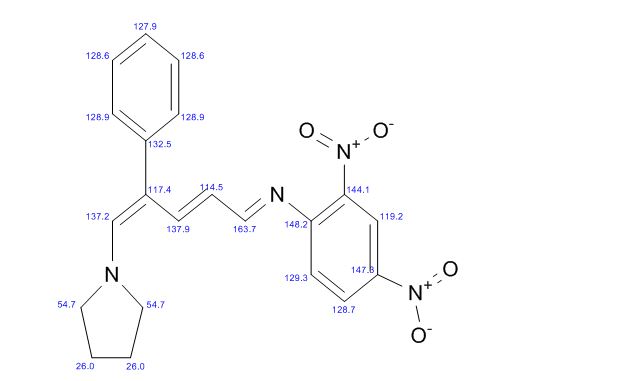

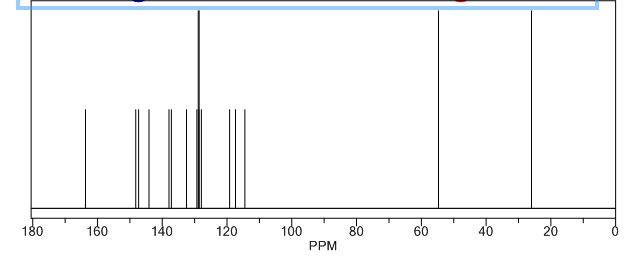

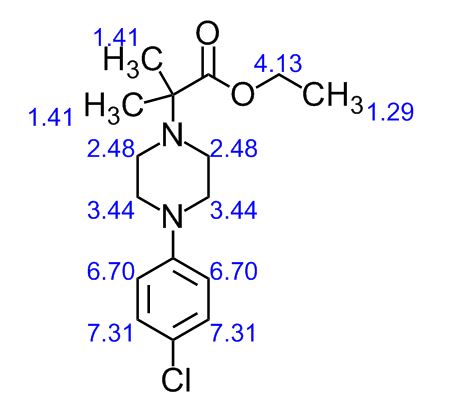

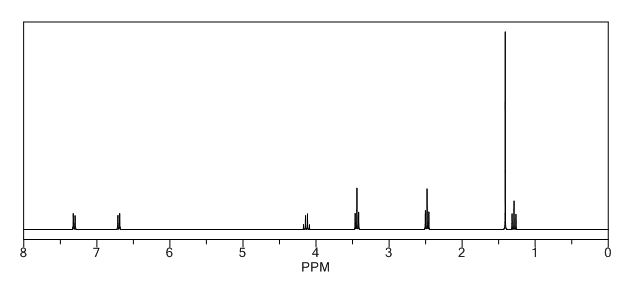

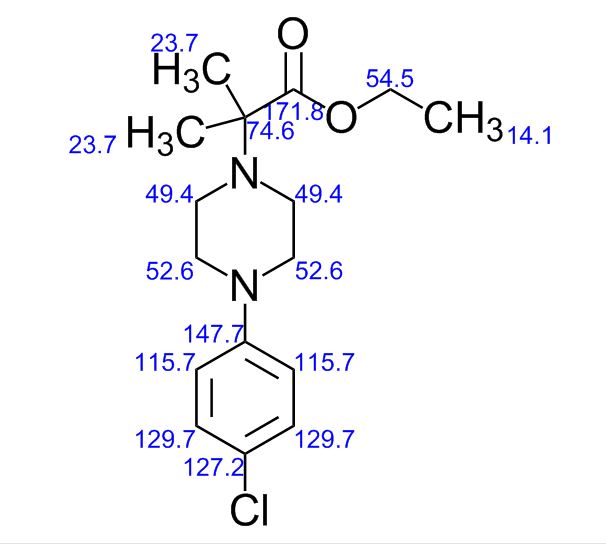

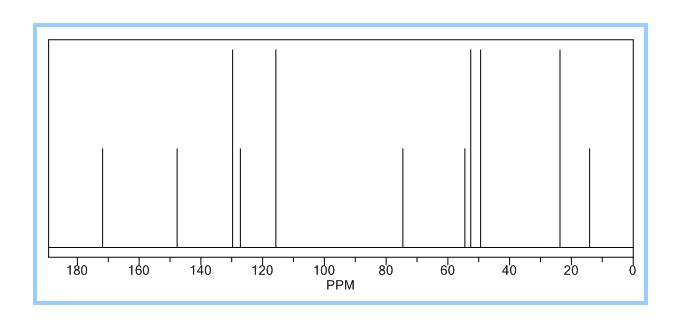

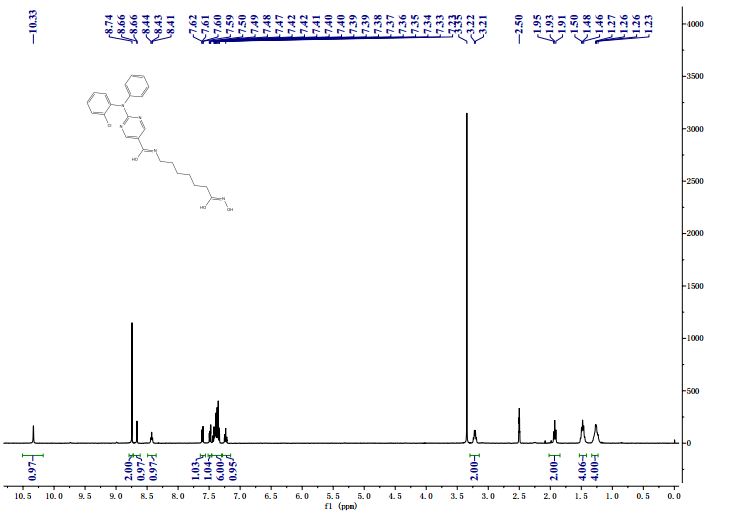

NMR

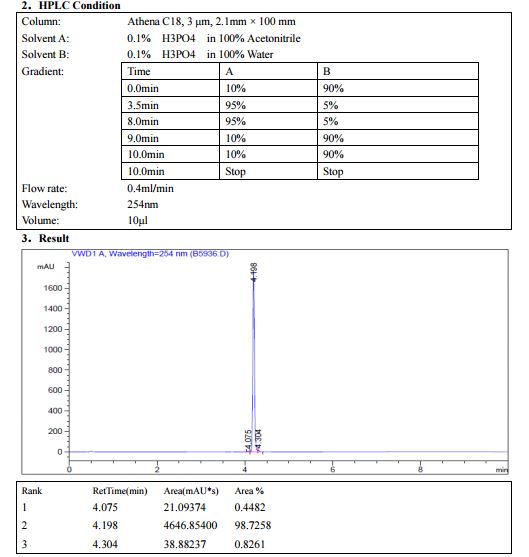

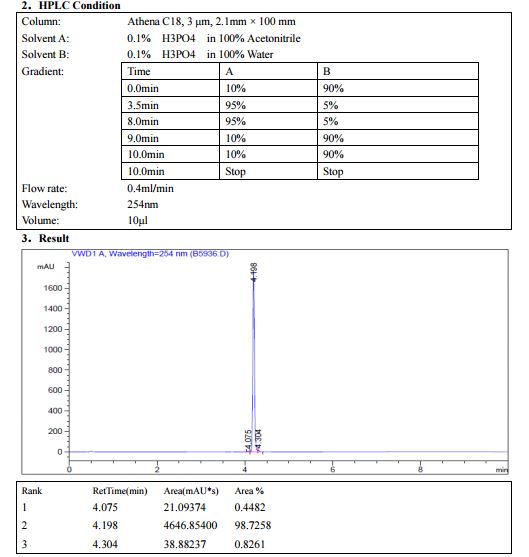

HPLC

////////////ACY-241, HDAC-IN-2, PHASE 1, CITARINOSTAT, 1316215-12-9

ONC(=O)CCCCCCNC(=O)c1cnc(nc1)N(c2ccccc2)c3ccccc3Cl

The presentation will load below

The presentation will load below